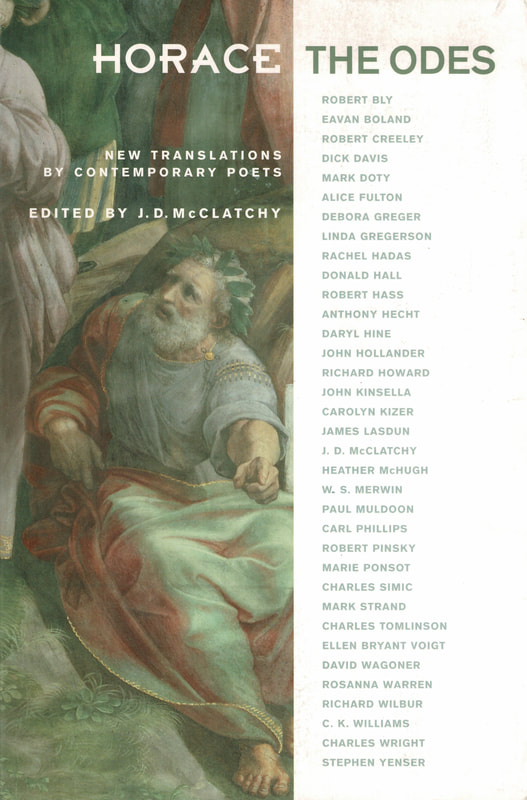

My favorite version of I.37, so far, is the translation by Ellen Bryant Voight: The translation was published in J.D. McClatchy, ed., Horace: the Odes (Princeton, 2002, p. 103), a volume well worth owning if you’re interested in the odes. Around thirty-five leading poets from the US, the UK, and Ireland were “specially commissioned” to write the translations (“Introduction,” 5). Voight's translation (see below) is a model of clarity and craft. The poem makes admirable use of alliteration (for example, "dizzy with desire and drunk," "the hawk harasses the helpless dove, / or the hunter the hare"). As the poem nears the conclusion, slant rhymes begin to point line ends, culminating in the long i sound that caps the last four lines. I.37, translated by Ellen Bryant Voigt

Now it’s time to drink, now loosen your shoes and dance, now bring around elaborate couches and set the gods a feast, my friends! Before, the time wasn’t right to pour the vintage wines, not while that queen and her vile brood of advisors, dizzy with desire and drunk on luck, were busy in deluded plots against us. What sobered her up was seeing her fleet on fire-- hardly a ship survived—nightmare she woke to sending her fleeing, flying, from our shores, Caesar at the oars in close pursuit-- the way the hawk harasses the helpless dove, or the hunter the hare in the snow-packed open field-- intent on dragging the monster back in chains. And yet the death that she resolved was grand: a woman who did not shrink from the drawn blade, who did not try to slip away and hide, she looked straight at the palace now in ruins, her face composed, and without blinking took into her arms the scaly venomous snakes in order to drink each drop of their black wine, and by that cup this woman of such fierce pride made the triumph hers: that she would die not as a slave, and not as someone’s prize. Edited 2 Nov 2023, 3 Feb 2024

0 Comments

The Berlin Cleopatra, a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC (around the time of her visits to Rome in 46–44 BC), discovered in an Italian villa along the Via Appia and now located in the Altes Museum in Germany. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cleopatra#/media/File:Kleopatra-VII.-Altes-Museum-Berlin1.jpg) The ode is among Horace’s most famous, in part because it brings us a contemporary view of a great historical moment, the defeat and death of Cleopatra. But it’s also appreciated because of its surprising shift in tone and point of view: the Romans’ “scornful opprobrium” of Cleopatra’s drunken self-delusions (David Ferry, translator, The Odes of Horace, 10) becomes admiration of her clear-eyed resolution at the end. “Now is the time to drink” is the governing conceit—the Romans in celebration of their victory over the queen drunk on her fantasies becomes Cleopatra’s metaphorical drinking in (conbiberet) of the asp’s venom. The Romans would humiliate her by parading her, a dethroned queen, in a grand triumph; but she chooses her own private victory.

According to Eduard Fraenkel (Horace, Clarendon Press, 1957, 158-161), Cleopatra was "the nation's most dreaded enemy"; and news of the capture of Alexandra and of her death a few weeks later brought joy to the people of Rome. Cleopatra was viewed as a prodigy (monstrum), wonderfully and horribly outside the ordinary. But once "the feeling of horror recedes..., admiration takes its place. At the end of the poem written to celebrate Cleopatra's defeat her greatness dominates over everything else." Here's David Ferry’s translation: At last the day has come for celebration, For dancing and for drinking, bringing out The couches with their images of gods Adorned in preparation for the feast. Before today it would have been wrong to call For the festive Caecuban wine from the vintage bins, It would have been wrong while that besotted queen, With her vile gang of sick polluted creatures, Crazed with hope and drunk with her past successes, Was planning the death and destruction of the empire. But, comrades, she came to and sobered up When not one ship, almost, of all her fleet Escaped unburned, and Caesar saw to it That she was restored from madness to a state Of realistic terror. The way a hawk Chases a frightened dove or as a hunter Chases a hare across the snowy steppes, His galleys chased this fleeing queen, intending To put the monster prodigy into chains And bring her back to Rome. But she desired A nobler fate than that; she did not seek To hide her remnant fleet in a secret harbor; Nor did she, like a woman, quail with fear At the thought of what it is the dagger does. She grew more fierce as she beheld her death. Bravely, as if unmoved, she looked upon The ruins of her palace; bravely reached out, And touched the poison snakes, and picked them up, And handled them, and held them to her so Her heart might drink its fill of their black venom. In truth—no abject woman she—she scorned In triumph to be brought in galleys unqueened Across the seas to Rome to be a show. (David Ferry, The Odes of Horace, p. 71. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition.) Edited, 18 Oct 2023; 20 Oct 2023. Comments? Send them to jsabsherphd@gmail.com  Source: https://downunderpharaoh.patternbyetsy.com/listing/507220168/egyptian-art-cleopatra-dressed-as-the This is the beginning of several posts, possibly nonconsecutive, on Horace's Ode 1.37, the famous ode on Cleopatra. I begin with the Latin text and a literal translation. I don't read Latin myself, except for the simplest sentences, so I will be relying on others' translation and scholarship.

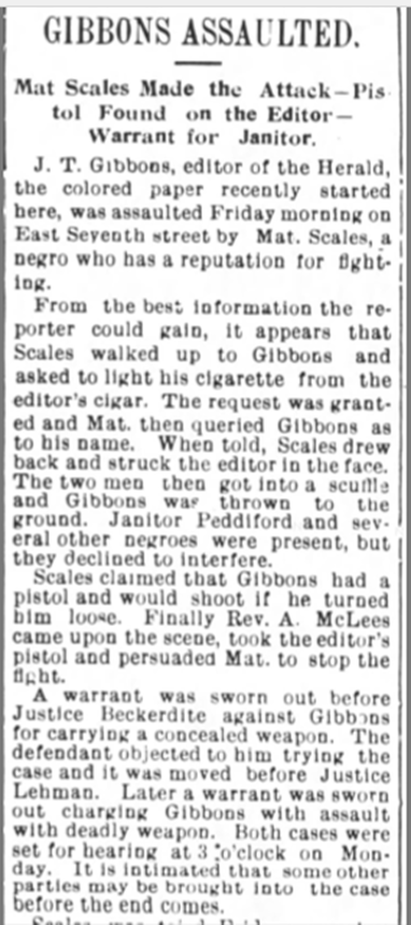

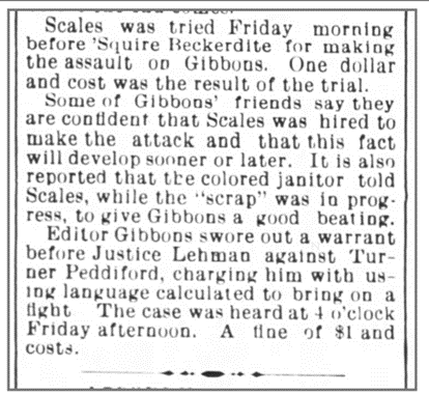

Ode 1.37 Nunc est bibendum (https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Odes_(Horace)/Book_I/37) Nunc est bibendum, nunc pede līberō pulsanda tellūs, nunc Saliāribus ōrnāre pulvīnar deōrum tempus erat dapibus, sodālēs. antehāc nefās dēprōmere Caecūbum cellīs avītīs, dum Capitōliō rēgīna dēmentīs ruīnās fūnus et imperiō parābat contāminātō cum grege turpium morbō virōrum, quidlibet inpotēns spērāre fortūnāque dulcī ēbria; sed minuit furōrem vix una sospes nāvis ab ignibus, mentemque lymphātam Mareōticō redēgit in vērōs timōrēs Caesar, ab Italiā volantem rēmīs adurgēns, accipiter velut mollīs columbās aut leporem citus vēnātor in campīs nivālis Haemōniae, daret ut catēnīs fātāle mōnstrum, quae generōsius perīre quaerēns nec muliebriter expāvit ēnsem, nec latentīs classe citā reparāvit ōrās, ausā et iacentem vīsere rēgiam voltū serēnō, fortis et asperās tractāre serpentēs, ut ātrum corpore conbiberet venēnum, dēlīberāta morte ferōcior: saevīs Liburnīs scīlicet invidēns prīvāta dēdūcī superbō, nōn humilis mulier triumphō. Literal English Translation (from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Odes_(Horace)/Book_I/37, with revisions from the prose translation by Steele Commager, The Odes of Horace, 90) Now it is time to drink; now with loose feet it is time for beating the earth; now it is time to decorate the gods' sacred couch for Salian feasts, comrades. Before this it was forbidden to draw forth Caecuban wine from old stores, while the Queen-- still plotting mad ruin for the Capitolium and planning the destruction of the state with a foul herd of men shameful with disease—was wild with all sorts of hopes, and drunk with sweet fortune. But it diminished her frenzy when scarcely one ship escaped from the flames, and Caesar reduced her mind, inflamed with Mareotic wine, to true fear, as he flew from Italy with straining oars, as a hawk pursues tender doves or a swift hunter the hare on the plains of snowy Haemonia, that he might put in chains that monster of fate. Wanting to die more nobly, she did not like a woman tremble at the sword, nor repair to hidden shores with her swift fleet, but, having dared to see her fallen palace with a tranquil face, she bravely took to herself the harsh-scaled serpents and drank in their black venom with her whole body, in her chosen death growing fiercer. Unwilling to be taken away by Liburnian warships, no humble woman, she scorned to be led as a private citizen, a captive in our triumph. Updated with photo, 18 Oct 2023. Send comments to jsabsherphd@gmail.com Tuttle defender in focus: Mat Scales To think clearly in human terms you have to be impelled by a poem.—Les Murray  The Western Sentinel (7 Apr 1898, 1) The scope of this study is so small, I might perhaps be excused from concerning myself with methodology. But there are three points that I think deeply important to the study of history and even our lives, especially in a time where life and liberty seem threatened on many sides. Openness to the future To make the first point, I quote from Clive James’s essay on Golo Mann, the great German historian: “In his Zeiten und Figuren (Times and Figures) (1979), Golo Mann expounded his key concept of Offenheit nach der Zukunft hin—openness to the future. He didn’t just mean it as a desirable trait of personality but as a necessary qualification for the historian. By an effort of the imagination, the historian must put himself back into a present where the future has not yet happened, even though he is looking back at it through the past. If a narrator knows the future of his hero, he, the narrator, ‘is bound to tinge even the simplest narrative with  irony.' Succumbing too easily to the ironic mode is a cheap way of being Tacitus. The true high worth of Tacitus depended on his being always aware that tragic events had been the result of accidents and bad decisions, and the depth of the tragedy lay in the fact that the accidents need not have happened and the decisions might have been good. In a predetermined world there would be no tragedy, only fate. With his revered Tacitus as an example, Golo Mann was able to form the view that fatalism and frivolity were closely allied: to be serious about history, you had seriously to believe that things might have been otherwise.” (emphasis added; Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts, pp. 423-424, Norton, Kindle Edition) To believe that a political trend is inevitable makes it hard to resist, especially in any organized, effective way; the aura of inevitability makes resistance seem a fool’s errand. Some will fight for lost causes, but when a catastrophe is thought to be unavoidable, many will look for a way to navigate their own way through, let the devil take the hindmost. As a disaster develops, this may become the only choice, but I’m talking about those earlier moments when hope is still realistic and inevitability is a construct of demagoguery. Imagination as method The second methodological point is the importance of imagination in understanding the truth of history. As Simon Leys notes, “At a certain depth …, all writings tend to be creative writing, for they all partake of the same essence: poetry. History (contrary to the common view) does not record events. It merely records echoes of events—which is a very different thing—and, in doing this, it must rely on imagination as much as on memory. Memory by itself can only accumulate data, pointlessly and meaninglessly….” ("Lies that Tell the Truth," The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays. New York Review Books, Kindle Edition, 43.) Imagining Mat Scales Here's a tentative imaginative reconstruction involving Matt Scales, one of Tuttle’s defenders. In the last post, I mentioned P. T. Lehman, a Republican activist and minor officeholder in Winston-Salem; he was a justice of the peace. In the campaign of 1898, he played a prominent local part in an insurgency within the Republican Party that offered its own slate of biracial candidates. One of the ringleaders was the Rev. Jethro T. Gibbons, an immigrant to the US from the West Indies and a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Shortly after arriving in Winston-Salem, Gibbons started a newspaper, The Twin-City Herald, apparently for the sole purpose of intervening in the 1898 campaign. (So far as I know, no copies survive.) The paper surprised and dismayed Republicans by attacking them rather than Democrats. At the time it was suspected that his activities were funded by Democrats. (See the Union Republican, 24 March 1898, 2. Bertha Hampton Miller shares this suspicion in her 1981 dissertation, Blacks in Winston-Salem, North Carolina 1895 – 1920.) The alliance with Lehman may support the suspicion. Just two years later Lehman was willing to openly betray his party by supporting the Democrats’ project to disenfranchise more than half its voters; perhaps in 1898 he was prepared to do so surreptitiously by tactics calculated to weaken and divide Republicans. This is only a guess, of course, but it seems at least possible. Now we come to the part played by Mat Scales. Scales was an African American reasonably well known in the white community with a reputation for fighting. For his role in defending Tuttle, Scales was found guilty but received no punishment: he was “discharged without payment of costs” (“The Rioters Sentenced,” Western Sentinel, 29 Aug 1895, 1). We don’t know Scales’ role in the defense of Tuttle, nor the reason for the disposition of his case. In 1897 occurred an incident that throws light on Scales’ character. In the summer, many Winston-Salem citizens traveled by train to nearby towns in brief holiday excursions. On Monday, August 2, an excursion organized by three Black Sunday Schools was returning from Reidsville, a popular destination. Two men on the train began fighting, and when one pulled a knife and began to attack, Scales recruited two other men to help him stop the fight, take the knife, and “arrest” the attacker; on return to town, he was handed over to the police and jailed. Both local papers covered the incident; the facts reported were similar, but The Western Sentinel’s article was sneering in tone and racist in language, even though Scales’ quick action prevented serious injury and possibly murder, and for no obvious gain. I think the character of Scales may be captured in the paper’s intended insult, that he “deputized himself to arrest” the attacker ("Row on the Excursion," 5 Aug 1897, 3). Protecting this victim is consistent with Scales’ joining in the effort to defend Arthur Tuttle from lynching. To purport to understand a character based on two incidents and a prejudiced account is tenuous, an imaginative more than an inferential link. I put it down as a working hypothesis. In spring of the following year, Scales and Gibbons had a dramatic encounter. Gibbons had just launched his newspaper, as described above. Its attacks on Republicans aroused indignation in the Union Republican and probably among Republicans in general. In April, Scales met Gibbons in the street and attacked him with a blow to the face. A struggle followed, stopped only when a bystander took Gibbons’ gun. Gibbons suspected that Scales was paid to attack him, but I’m not aware of any evidence one way or the other. Based on the hints we have of Scales’ character, I wonder if he did not act on his own, or required only the barest of hints to act, to defend the community against political betrayal. Not that the violence was warranted or effective. (The political alliance between Lehman and Gibbons may already have existed, since Gibbons requested that the case against him for carrying a concealed weapon be transferred to Justice of the Peace Lehman.) Aftermath--Gibbons In May, shots were fired into Gibbons’ house at night. At the end of the year, he was assigned by his bishop to lead a congregation in Method, near Raleigh, and early the next year he published a bitter attack against Republicans in the state’s most influential white supremacist paper, Josephus Daniels’ News and Observer (“Another Negro Speaks,” 12 January 1899, 5). Aftermath--Mat Scales In late April, the US declared war against Spain, and Scales enlisted in the army, probably not long afterwards; his reasons are not known to us, of course. In 1899, he received a dishonorable discharge for riot and was imprisoned in Fort Leavenworth for two years. Again, we do not know his motives, but we do know the general context. The all-Black NC 3rd Regiment had Black officers, a fact used in the Democrats' 1898 campaign as evidence of “Negro domination” of the government. The soldiers were mistreated by the white communities where they were stationed—in Fort Macon, where a near riot in Morehead City was occasioned by a conflict between the soldiers and white civilians; in Fort Poland, near Knoxville, TN, where the soldiers were rocked and fired at; and in Camp Haskell, near Macon, GA, where four NC soldiers were killed and the perpetrators found innocent. I do not know the circumstances and motivations of Scales’ offense, but perhaps he had reasons enough to justify to himself his actions based on his self-understanding as a defender and protector, thought we cannot rule out the possibility that he acted out of anger and frustration. Imagining the individual This is the third principle: understanding history through imagining the lives that composed it, even though “individual lives … [are] in the end unknowable,” especially when they could not or did not speak for themselves (Clive James, “Lewis Namier,” Cultural Amnesia). Revised 1 October 2023  Richmond Planet (17 Aug 1895, 2) Perhaps the wisest words about the defense of Tuttle are from this item, probably but not certainly written by the editor, John Mitchell, Jr.: in preventing a lynching, Tuttle's defenders "were there to maintain the majesty of the law and not to violate it." One of Tuttle’s defenders, Samuel Toliver, was or shortly afterwards became the local agent for the Planet. He appears to have come to Winston-Salem from Richmond, and occasionally traveled to Richmond to confer with Mitchell. **** The Tuttle defenders in focus—Several of the defenders had modest political ambitions; that is, they had the American, if not human, desire to govern themselves and to represent a constituency: • In 1891, John Mack Johnson or someone with a similar name was on the Colored School Committee. • In 1892, Peter Owens was on the credentials committee of the county Republican convention, and in 1894 he was named as a delegate to the state Republican convention. • In 1896, Frank Carter was elected as a town alderman. • In 1898, John Mack Johnson (also spelled McJohnson) and Henry Neal participated in the campaign to select Republican candidates for the general election. Johnson sided with insurgents (the Rev. J. T. Gibbons and others), apparently angry that the electoral successes of 1894 and 1896 had not provided more patronage positions for blacks. • In the same year, Sam Toliver chaired a meeting of the Republican party in the 1st ward. • In October 1898, Neal gave a speech that touched on the relationships between black men and white woman. This was a hot topic in the campaign, as I will discuss in a later post. Neal’s speech was reported by a hostile source, The Western Sentinel, no doubt with the intent of keeping this issue alive. But we don’t know what Neal actually said—all we have is the brief quotation used by the Sentinel to inflame racist opinion. **** The situation in 1898--In upcoming posts, to provide the political background in which our fifty men acted to defend Arthur Tuttle, I will comment on two prescient letters to the Union Republican published in August and September 1898, in the run-up to the election. The anonymous writer was from Ruffin, NC, so I will call his letters the “Ruffin letters.” To understand these letters requires an introduction to the political situation in 1898. I know this is an odd way to proceed, but these blogposts are a very rough draft of the projected book, and I am writing about topics as they occur to me. During the isolation of the pandemic, my research made me increasingly aware of the tactics used by the Democratic Party in North Carolina to prepare the way for the formal imposition of Jim Crow in 1900. In the campaign of 1898, these tactics were out in the open. In the eyes of those living in North Carolina at the time, the imposition of Jim Crow—by which I mean the formal disenfranchisement of blacks (and poor whites, too)—was not inevitable. It’s too easy for us to suppose that, because it did happen, it had to happen. But it was not easy to achieve—it took the combined efforts of the white Democratic ruling class, propaganda by most of the newspapers in the state, the demagoguery of politicians (faithfully repeated in the newspapers), and the terror campaign by the Red Shirts, those direct lineal descendants of the KKK and the Gadarene swine. It was also suspected, then and later, that some well-known black leaders were bribed into attacking the Republican candidates and party. Newspapers helped the Democrats seize effective control of political language in the service of white supremacy. The rule by and for the white elites was called “the Democracy”; allowing Republicans to govern or blacks to vote was, by definition, anti-Democratic. Every means was justified to ensure triumph of “the Democracy,” much as demagogues in every epoch of our republic shout democracy while silencing dissenters. The meaning of “the Democracy” was made quite clear in the party’s handbook for the 1898 election:  The triumph of Jim Crow was also ensured by the feeble campaign mounted by the opposing parties, the Republicans and the Populists. The fusion of Republicans and Populists had enjoyed stunning successes in the elections of 1894 and 1896; those successes provided the immediate context to the defense of Tuttle in 1895. But by the election of 1898, the Fusion legislative agenda had been largely enacted, including measures to expand the franchise and ensure the integrity of the vote. Now Republicans and Populists differed on the way forward. They dithered and they bickered. As we will see in the Ruffin letters, their only shared campaign issue was opposition to the Democratic party. A more fundamental issue was social equality between the races. To some extent, white Republicans were willing to grant a degree of political equality to blacks, but they resisted social equality, particularly in any setting that brought black men into relations with white women or placed blacks in authority over whites. Only a courageous genius could have navigated those stormy straits. But white Republicans—reluctant to appoint their African American allies to lucrative patronage positions or elect them to higher office—were not courageous or generous, and all too were eager to find an excuse to abandon the backbone of the party. For they were also dunces. For example, in 1900, P. T. Lehman, a Republican justice of the peace in Winston-Salem, deserted the Republican governor to support the Democrats’ constitutional amendment limiting the black franchise. He thought that, by removing “the Negro question” from politics, the Democrats would lose their major political issue and their ability to win offices. But this was suicide wrapped in an illusion: there could be no important Republican victories in NC without black votes. Worse, it was a betrayal. Lehman died in 1924. Voting rights were not restored to blacks until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The next Republican governor was not elected until 1973. This then is the context in which the anonymous letter writer from Ruffin, NC, gave his prescient take on the political situation in late summer 1898. Updated 14 Sept 2023  Star of Zion (Charlotte, NC, 22 August 1895, 2.) The Star of Zion was founded in 1876 by the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Zion Church and is still published today. The reference to "traitors" probably refers to those who received lighter sentences for identifying the arrested men. As some readers of the blog may know, I have slowly—very slowly—been creating a group biography of the fifty men who, in August 1895, surrounded the jail in Winston-Salem, NC, to prevent the lynching of a young black man, Arthur Tuttle, who had killed a white policeman in May. Many more were present, but we know the names of almost fifty participants—all men, all African American—because they were arrested, for riot and other charges, and some of their trials were reported in the newspapers. (An interview more than 70 years later stated that Arthur Tuttle’s sister, Ida, was also present, but she appears not to have been arrested.)

Very little from these men has survived in their words; those few words are not related to the defense of Tuttle and come to us through the filter of white editors. As we will see, we do have the voices of Simon G. Atkins, a prominent black educator and institution builder in Winston-Salem, and R. B. Garrett, an otherwise unknown man who wrote to the Richmond Planet. I have been intermittently posting on this topic since July 2022 and intermittently researching for much longer. It seems to me natural to be curious about men who risked their lives to prevent murder. Who were they? Where did they come from? What were their familial, social, and institutional connections? How did they make their livings? What happened to them? What gave them the pluck to make a stand? Here are my posts grouped by topic: (1) “The Tuttle family and the Riot” (2) Three posts on group biography, or prosopography: “Prosopography: Towards a Collective Biography” “The Method and Value of Prosopography” “Prosopography in 1895 Winston-Salem: Some Limitations” (3) Five posts on Arthur Tuttle’s protectors and their connections with themselves and others: “Overview of Tuttle’s Protectors” “Connections (1)—Walter Tuttle, Yancey Simpson, Green Scales, and Ellis Matthews” “Connections (2a)—Samuel Toliver and Friends” “Connections (2b)—Samuel Toliver, Peter Owens, John Mack Johnson, and W. H. Neal” “Connections (3)—Micajah (Cager) Watt and the Depot Street School Neighborhood” My next posts will consider the context of the times in the state and in Winston-Salem, then share and comment on contemporary documents that illustrate the issues. For questions or comments, please email me at jsabsherphd@gmail.com.  Brillig, self-described as “a micro lit mag,” is edited by Deborah Doolittle. But apart from the work of soliciting and choosing poems to publish, the term “edited” here means handcrafting, illustrating, and assembling the poems into a star book—“a book-art edition [that] opens into a star when the front and back covers are pressed together” (from the introduction). The book is beautiful in design and execution. Publishing it must be time-consuming and painstaking, but the result is a satisfying micro-gallery of graphic and written art that I highly recommend to the reader and writer. The 2023 winter/spring issue contains poems by five poets whose poems “share an underlying sense of humor regarding our human condition.” Doolittle solicits poems that “by definition are both ‘brilliant and big’ but packed into a tiny space,” no more than twenty lines in length. It is difficult to single out a representative poem, but this poem by Davonna Thomas captures the tone of the issue. Yes (and) Cam Driving home on a hot August day, the lingering singe of a long summer. I hear a shift in the silence, like I always could just before he spoke. “Acting is hard,” he observes in response to some unspoken prompt. “I have to say the lines exactly right; I don’t wanna get them wrong.” Red light. Another loud pause, the firing of neurons. “Improv. Improv is so much easier.” I push back gently, like I always do. Do you not enjoy acting? Black eyelashes blink over blue as ideas crystallize. “Acting-- fun and stressful. Improv—fun and FUN.” Would you believe, weight on each word, that many people find it terrifying to make up lines on the spot? Puppy dog head tilt. “But why though? You literally have to do it all day, every day.” Hmmm. Green light. Quiet and closed mouth as I lift my foot from the brake, not quite ready to accelerate. You’re right, buddy. Lines on the spot. Every waking moment. One of the great pleasures of Brillig is the art that accompanies each section of the issue. Below are two pages and the art that accompanies them. One page provides information on how to subscribe, the other is a bio of a contributor, Joseph D. Milosch. In addition to Davonna Thomas, whose poem is shown above, the other contributors are David Lavar Coy, Tom Plante, and George J. Searles. If you have comments, please send them to jsabsherphd@gmail.com. I will pass them on to Deborah.

Night scene on the battlefield, showing Verey lights being fired from the trenches, Thiepval, 7 August 1916. (https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205072490) In “Nocturne,” the final poem of Henry-Jacques I have translated so far, a night in the trenches becomes a dark night of the soul. He is becoming part of the darkness; the darkness is becoming part of him. He must find a new language—using words that war “has not stained”—to understand the shadow, both “hard” and “ungraspable,” that holds him.

Nocturne by Henry-Jacques Cold night, with supple tentacles winding round the neck and shoulder: here I am, I don’t know where, stooping in a narrow cell. From the pit around me rise the arcana, opaque and hard. I grope the earth as if fumbling cards. Tonight hands must be my eyes. Like a beast in the teeth of a snare, my will contorts itself, dismayed that in this gloom I am no more than shadow merging into shade. I feel as if I were being poured into hard, ungraspable shadow that, through fissures I cannot see and without noise, slips into me. The mind, mustering all its power to leave the dark in which it’s caught, floats like wood, emptied of thought, on the black, slow-moving water. It hears the murky silence made of whispering voices in the thousands flowing together in human currents. Huddled in the trench we wait. A little more and the naked mind dares question its fate; and now, escaping the words that war has stained, it senses truths it never knew. And from the throat of the pit a noise rises, a funereal voice: “What are you doing in this shadow?” And my heart responds, “I do not know.”  Source: Pinterest UK Henry-Jacque’s first collection of poems on the First World War is called La Symphonie héroïque; it won a prize, the Prix de la Renaissance, in 1922. Henry-Jacques (1886 - 1973) was a pseudonym; his name at birth was Henri Edmond Jacques. The title and structure of the book reflect his interest in music; after the war, he published two music journals and was recognized as a musicologist. In addition to two other books of poetry based on his wartime experiences, he was a journalist, a novelist, an adventurer at sea. He circumnavigated the globe several times, twice sailing around Cape Horn.

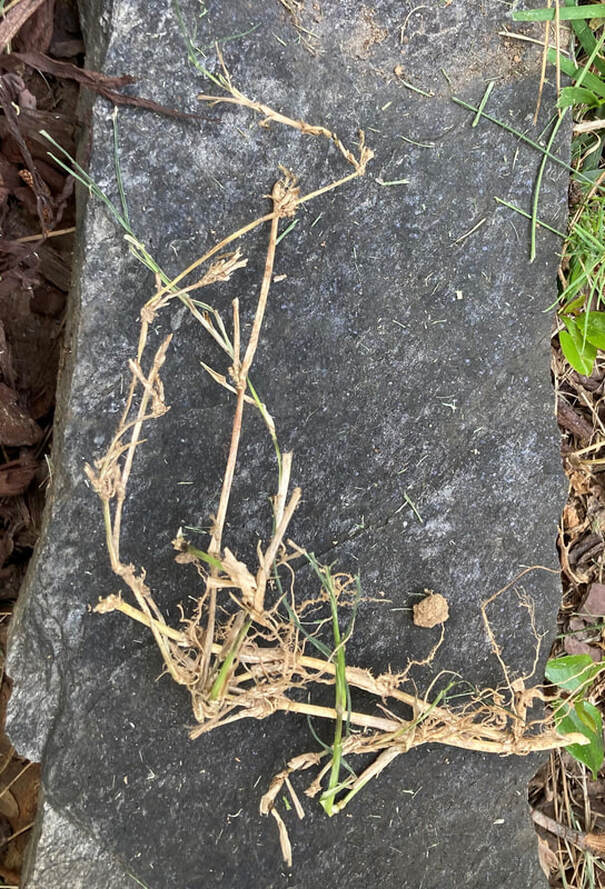

In “Landscapes” (“Paysages”), a soldier is entering the trenches and marching towards the dangerous front line to work as an observer, as in the poem I recently posted, “Assassin Poet.” As other stories and poems from the war reveal, the trenches were confusing and disorienting, even for an experienced soldier; the aerial photo above gives some idea. The front and the war were, as the poem says, everywhere. Enemy planes, mines placed by sappers in tunnels under the trenches, artillery shells, and gas attacks affected far more than the designated front line. Landscapes by Henry-Jacques I. In the wall, wide as a porch, a hole that opens on a hole, barbed wire that flays the skin. A hand notice riddled with holes: "Trench four, to the lines,” to war, over there, everywhere. As black as vine shoots, the pickets all skin and bone show their signs as they stand watch on top of sacks cast up on this petrified sea. II Before you is the gate of hell; pass through, but watch out for the front, that too vague something: the front. It’s there, above, below, in the air, deep opening into deep, impalpable, an anguish clinging to the flesh. There, where your eyes come to rest, that ridge—it’s near yet very far, the end of the world, that low crest, right there… a little farther… a bit less. III A little closer, a little farther… the trench runs to every quarter; drifting away but never moving, everywhere and nowhere fleeing in broken angles of separation that snap even the greatest strength. But fighting the weary, dejected fear of anything that moves or stirs, of even the air tense with silence, the heart divines that it is there! IV The outpost’s distrustful eye, its furtive spyhole, narrow transom cut in the never-ending wall. Stretching outward his watchful mind, a man looks through the hole and hazards his eye to those he cannot trust. He scrutinizes the soul of war, but sometimes, slipping across the edge, his gaze takes in the whole of death beyond life, beyond the earth.  Wire grass, or bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) Wire grass, or bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), is a nonnative perennial grass. Like many weeds that come to the casual gardener’s attention, it is persistent and hard to remove. It spreads by above-ground runners (called stolons) and underground rhizomes that can reach a foot or more into the ground. Its stem is tough, and I surmise the origin of its name. It’s said that the plant can grow back from small sections of a stolon or rhizome. It is not a pretty plant, but I find a certain elegance in its leggy architecture.

I had this sprig sit for a photoshoot this afternoon. I’m digging up part of our front lawn for a bed of perennial native plants and the occasional annual. It’s a sunny spot. I welcome recommendations. Message me on Facebook or send an email to jsabsherphd@gmail.com. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed