|

To comment, please email me at [email protected].

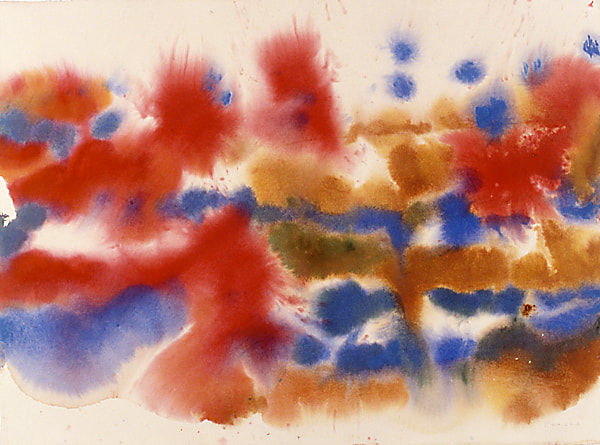

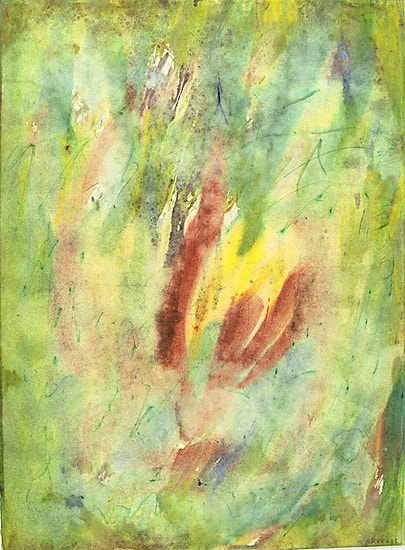

A few years ago, through Ancestry.com DNA testing, I was introduced to the art of my great aunt, Cynthia Reeves Snow, an accomplished artist who generally signed her works Cynthia Reeves. She was the half-sister of my illegitimate grandfather, Elbert. Long after Elbert's death, I learned that his father had married a few years after fathering Elbert, and that Elbert's relationship to his father was recognized by his father's legitimate children and he was sometimes invited to family events. Through Ancestry, I became acquainted on-line with Cynthia's daughter-in-law, who with her husband had inherited many of Cynthia's paintings. She wanted them to be seen, not locked away in a museum's vaults (the University of Connecticut where Cynthia taught for many years was willing to give the paintings a home), so she offered me as many as I liked. I gave many to my siblings and I hope, post-COVID, to give some to cousins. I will be keeping several of them, but I have not yet had them framed--a project I hope to begin this year. As part of my promise to make the paintings available, I have already posted a few on Facebook; they are featured on this website, too, and I hope to use at least one as the cover of a future book. Beginning at the left top, these paintings are: Autumn Full Cycle (1971); Bright Day, Swamp Maple Pattern (1960s); October Landscape (mid-1960s); Spring Song (1995); Rhythmic (mid-1960s); and My Home Was in the Hills - New River Valley (1991).

0 Comments

Email comments to [email protected]

Professional deformation was first introduced to me--by a student at the University of Poitiers, I think, who used the term in a joking comment and then had to explain the joke--when I was in France serving as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Déformation professionnelle is a term for how profession shapes understanding and perception of the world. The passage below, from Ryszard Kapuściński, Travels with Herodotus (Vintage, 2008), 149-50, gives a vivid illustration of a radical form of such deformation: "They [Alexander the Great and party] encountered the first delegation [from Persepolis] immediately beyond the river. But these ragged figures differed greatly from the elegant opportunists and collaborators with whom Alexander hitherto had dealings. Their cries of greeting, as well as the branches of supplicants they carried in their hands, signified that they were Greeks: people either middle-aged or elderly, perhaps former mercenaries who had fought on the wrong side against the cruel monarch Artaxerxes Ochos. They were a pitiful, downright ghastly sight, because each of them was horribly disfigured. In accordance with the typical Persian method, they had all their ears and noses cut off. Some were missing hands, others feet. All had a disfiguring brand on their foreheads. 'There were people,' says Diodor, 'who were skilled in the arts and in various crafts, and did good work; they had their appendages cut off in such a way as to leave only those necessary for performing their profession.'" I worry more about ideological deformation, that is, cutting off perceptions, sympathies, and openness to ideas and feelings that are not congenial to our understanding of the world and how we fit into it. The Scene in an Alchemist’s Laboratory is from Wikimedia To comment, please send an email to [email protected].

“Strange Arts and Visual Delights” is the loose translation of the title of an Arabic manuscript acquired by the Bodleian Library in 2002. It consists of maps and astronomical diagrams, “most … previously unparalleled” in any surviving material in any language. Even though the preferred title is now The Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eyes, I will keep the title that so intrigued me when I first read it. (If you’re interested, read Jeremy Johns and Emilie Savage-Smith, “The Book of Curiosities: A Newly Discovered Series of Islamic Maps,” Imago Mundi 55 (2003): 7-24, accessible on JSTOR.) In the Renaissance and Baroque eras, “Kunst- und Wunderkammer” were rooms for the display of “precious artworks (artificialia), rare natural objects (naturalia), scientific instruments (scientifica), objects from exotic lands (exotica), and natural marvels that sparked wonder (mirabilia)” (https://www.kunstkammer.com/index.php/en/kunst-and-Wunderkammer). None of this is exactly germane to the purposes of this blog, except that I hope it will be various and curious, touching on any topics that interest me at a given moment, including poetry, regional and family history, politics, culture. I hope to be an observer of the passing (and many passed) scenes, good natured by preference but acidic when called for. You may disagree with me, but friends are those we love and respect, not those we agree with. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed