For Christ’s sake, everybody bugs everybody else.—Richard Nixon (1)

[T]he entire planet has become a whispering gallery, with a large portion of mankind engaged in making its living by keeping the rest of mankind under surveillance.—Marshall McLuhan (2)

"Daddy [Edwin Duncan, Jr.] was very proud about bugging the IRS, because this was war," [his daughter] said. "He carried the tapes openly around North Wilkesboro and joked about it." (3)

[T]he entire planet has become a whispering gallery, with a large portion of mankind engaged in making its living by keeping the rest of mankind under surveillance.—Marshall McLuhan (2)

"Daddy [Edwin Duncan, Jr.] was very proud about bugging the IRS, because this was war," [his daughter] said. "He carried the tapes openly around North Wilkesboro and joked about it." (3)

Part 7 - Bugging the Buggers [Draft 1]

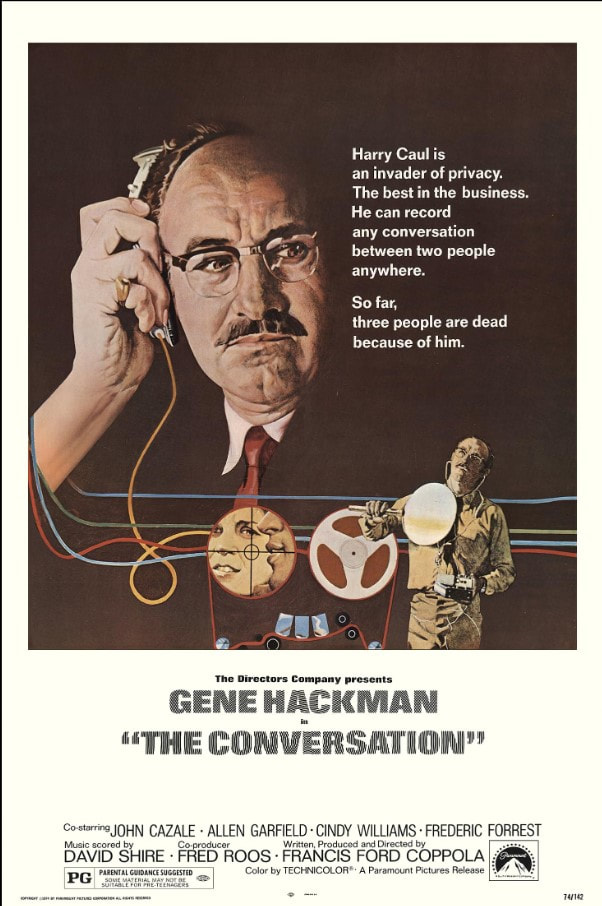

Poster for The Conversation. Source: IMDB

*****

Surveillance by bugs—that is, by miniaturized listening devices—became relatively common as transistors became widespread and inexpensive. (4) But the widespread use of wiretaps and other techniques, by the government and private parties, had long been a concern. The danger to privacy and to citizens’ Constitutional rights became a frequent theme of Congressional investigations, articles and books in the trade and popular press, and the movies. It is far too large a topic to treat here, so I will approach it by looking a little more closely at the men and organizations whose timelines tangle on this point and intersect in some way with my father's history.

A nickname for Francis Ford Coppola as a child was “Mr. Science.” Despite his mediocre grades, he was interested in science and technology. When he was 13 or 14, around 1952, he planted microphones around the family house to surreptitiously capture conversations. As he said much later, “‘[T]here was a tremendous sense of power in putting microphones around to hear other people’” (5). A landmark 1956 study in New York showed that many children who grew up to be professional eavesdroppers first became interested in covert listening at this age (6). Coppola was unique, not in his interest but in how he turned it into art in The Conversation; his interest was less in the technology and techniques of eavesdropping than in its effects on the eavesdroppers (5)—a theme reflected in my father’s story.

Marty Kaiser—who worked as a technical consultant for Coppola and later built and installed bugs to listen in on FBI conversations at the Northwestern Bank and—built his first ham radio rig at the age of ten (around 1945). Electronics and amateur radio provided an emotional refuge from his abusive father (7). By his early 30’s, Kaiser was an established professional in business for himself repairing industrial electronics equipment. He became involved in the intelligence field by chance. In the summer of 1966, he got lost trying to drive home after finishing a job at American Brewery, a job that included, he said, a liquid breakfast. Near the waterfront area of Baltimore, he noticed a sign, “U.S. Army Intelligence, Fort Holabird.” He managed to enter the fort and to talk to a captain in the Counter-Intelligence Corps. Kaiser offered to help fix any electronic equipment in need of repair, and he was given “a box of about a dozen transmitters and microphones the size of a cigarette pack and smaller.” He fixed them overnight.

It turned out that Kaiser had inadvertently made contact with “a centralized government depot for the purchase, distribution, and maintenance of intelligence property and apparatus worldwide,” and over the next few months he was called in “once or twice a week with repair jobs on a variety of surveillance equipment.” By the beginning of 1967 he was building the equipment. “Over the next ten years, I would sell more than 10,000 … preamplifiers to a wide number of intelligence agencies, including the FBI, CIA, Secret Service, the Drug Enforcement Agency, and the counterintelligence commands” of the armed services (8). One of the items he made in his early days “was the shoe-heel bug with a mercury battery,” a device about “the size of a tiny fingernail clipper” that was “hidden inside the false heel of a man’s or woman’s shoe” (9). In the 1998 movie, Enemy of the State, NSA agents place similar bugs, of Kaiser’s design, in the shoe heels of Robert Clayton Dean, the lawyer played by Will Smith.

Kaiser later claimed to be the inspiration for Harry Caul, the protagonist in The Conversation, an honor that has generally been accorded to Hal Lipset (10). Lipset was far better known to the public than Kaiser. He made national headlines in 1965 when, with “a transmitter inside a fake olive” he “amazed” a Senate Subcommittee with “the power of listening devices”; he captured the hearing’s opening statement with a miniature bug planted in a vase of roses (11). Unlike Kaiser, he was listed as a technical advisor in “the credits that overlay [The Conversation’s] celebrated opening zoom shot” (12), and in an early scene his name is mentioned as someone “preeminent in the field.” According to Michael Smith, the immediate inspiration for the film was an article on Lipset sent to Coppola in 1966, a year after the stunt in the Senate (10). A year later Coppola began work on the screenplay. As we have seen, Kaiser did not get involved in working with electronic eavesdropping devices till mid-1966, around the time the film was beginning to take shape in Coppola’s mind.

Of course, the characterization of Harry Caul may well have been drawn inspiration from more than one source. In an often-quoted line, Caul says “I don't care what [the people on the tape are] talking about. I just want a nice fat recording.” Kaiser felt the same: “the technical side of countermeasure work always challenged me creatively and intellectually. … [I]t was the work itself that energized me—not the process of secretly invading people’s lives” (13). Gene Hackman may have had his own inspiration for his role as Harry Caul. According to Kaiser, “my suggestions [for playing the last scene] included how Hackman should unscrew the mouthpiece [of the telephone] and inspect it for compromises” by pushing the hook switch “up and down … to see if the contacts were being made” (14), suggestions followed on screen. But the timeline indicates that, with regard to the screenplay, Lipset had priority over Kaiser.

Kaiser also claimed that, as an uncredited technical advisor to the film, he invented “the technical aspects of the last scene of the film.” In this scene, Caul tears apart his apartment looking for the bug he thinks must be there based on a threatening phone call: “‘We know that you know, Mr. Caul. For your own sake, don’t get involved any further. We’ll be listening to you.’” As we have seen, Caul carefully inspects the mouthpiece of his phone for bugs and finds none, there or anywhere else, including inside a plastic statue of the Virgin Mary that he shatters to inspect. The viewer may conclude that there is no bug, that the caller, a man named Stett (Harrison Ford), intends only to frighten Caul and use his already heightened paranoia to paralyze him. Or—and this is a possibility that Kaiser claimed responsibility for—the bug may be in the only still intact item in the room, Caul’s saxophone. In fact, the saxophone is (in Kaiser’s conception) part of the bug, serving as an antenna and microphone activated by an RF signal from outside Caul’s apartment (15). These things are not spelled out in the film, but the technical possibility supports the aesthetically satisfactory notion of the saxophone as a listening device. Here, Kaiser’s claims may well be true, especially since they are similar to his credited role as a technical advisor to a later movie, Tony Scott’s Enemy of the State (1998).

So far as the public record is concerned, Edwin Duncan, Jr., first became involved in eavesdropping in 1967 when he planted a bug behind a couch in the office of his sister’s husband “to ‘develop information for a divorce proceeding’” (16). (His brother-in-law worked for the bank in Winston-Salem, so the office was likely inside a bank building.) This was a typical use of listening devices: “in the late 1950s and early 1960s .... divorce cases [were] the primary driver of the market” in professional eavesdropping (17). As we will see, Duncan planted bugs in his own bank at least four times, and this, too, was not unusual: a Harvard Business School study published in 1959 showed that “a growing number of American companies were hiring wiretapping specialists both to spy on competitors--and to spy on themselves [emphasis added] .… [B]usiness executives around the country [admitted] that they routinely tapped their office telephones if they suspected employees of stealing, or if they feared the influence of unions among their workers” (18).

My sister remembers that the bank used bugs on at least one occasion to identify an embezzling employee. Daddy was apparently involved; he brought surveillance equipment home and demonstrated how he could transmit through the radio on a FM band (18a). Of course, in the two cases that concern us, Duncan was spying on the government agents who had temporarily set up offices inside the bank—hardly a typical scenario.

I do not know where Duncan obtained this bug or the training in how to use it. Nor do I know how he became aware of Kaiser; so far as I can tell, Kaiser worked behind the scenes until his testimony before Congress in 1975, a ruinous experience described in his memoirs, in a chapter appropriately called “Road to Ruin.” As we will see, Duncan does not seem to have met Kaiser until 1971 or 1972, when he wanted help in finding bugs that he suspected the IRS had planted in the bank. This was several years after Duncan bugged his brother-in-law’s office, several years before Kaiser’s testimony. After his Congressional testimony, Kaiser work in detecting bugs would hit the headlines in at least his home state, but before then he seems to have worked in the obscurity appropriate for his craft (19).

Kaiser is not always reliable—he is careless with dates, for one thing—but he is a player in the events surrounding Northwestern Bank in 1971-2 and 1977 and, for some key events, he is the only source.

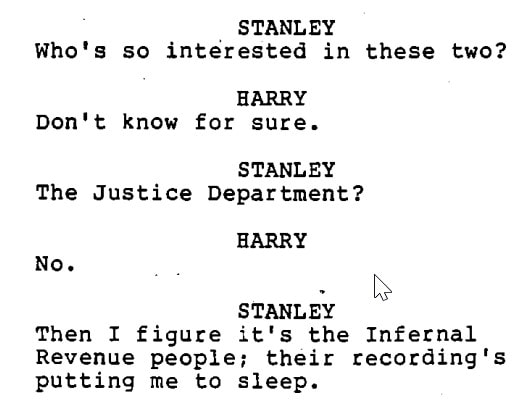

Excerpt from screenplay for The Conversation.

Source: script slug (https://www.scriptslug.com/script/the-conversation-1974)

Source: script slug (https://www.scriptslug.com/script/the-conversation-1974)

The IRS is Listening

Not long before Daddy’s life-changing experience in listening devices, a series of Senate hearings revealed the widespread, unauthorized use of illicit eavesdropping by numerous government agencies, including the IRS. Over the course of several months in 1965, Senator Edward V. Long’s Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure traveled around the country gathering testimony on “the pervasiveness of electronic eavesdropping” (20). One of the witnesses was Hal Lipset, with the famous false martini. Many of the revelations concerned the surveillance and eavesdropping techniques of the Internal Revenue Service. Hochman provides a useful summary:

“The first round of hearings came to an explosive climax in July–August 1965, when top officials from the Internal Revenue Service, an agency long suspected of illicit investigative activities, testified about the unreported use of illegal wiretaps in thousands of tax fraud and racketeering cases. One of the most sensational details of the IRS testimony was the disclosure of a ‘Technical Investigative Aids School’—in essence, a wiretap training program—for federal agents, located four blocks from the Treasury Department’s headquarters in downtown Washington. More than seventy government employees had attended the school between 1959 and 1964. Course offerings included ‘Amplifiers and Recorders,’ ‘Microphone Installation,’ and ‘Surreptitious Entry.’” (21)

The notoriety the IRS earned from its surreptitious eavesdropping is reflected by a scene early in The Conversation. While Harry Caul and his technician, Stanley, are on a stakeout in a van, Stanley complains about the boring conversations captured by IRS eavesdroppers.

As I have noted, the Duncan family believed they were in a “feud” with the IRS. Only a few details of the “feud” are available. In 1966, the bank recovered $200,000 or more from the IRS and, to celebrate his victory, Edwin Duncan, Sr., framed a copy of the check and hung it in the main lobby of bank headquarters in downtown North Wilkesboro (22). I do not have further details about the dispute with the IRS at that time, but upper management’s attitude toward government intrusion is illustrated by an anecdote from an FBI agent: he told my brother that Northwestern Bank was the only bank that had kicked him out during an investigation (23). The bank’s attitude towards the IRS is captured in an incident briefly mentioned in the newspapers: at some point, probably in 1971-1972, an IRS agent (presumably one auditing the bank) entered the bank cafeteria. This was taken by management as a deliberate provocation (24). It may have been intended as a challenge—a demonstration that the agent was not intimidated by the bank’s hostility. Or perhaps the agent just wanted lunch.

The revelations of illicit IRS eavesdropping during the hearings of Long’s committee must have roughly coincided with an IRS audit of the bank, the audit that resulted in back taxes, interest, and penalties of at least $200,000. One of the witnesses, the president of a supplier of missile parts to the Defense Department located in Asheville, North Carolina, gave the story a local angle (25). The stories probably caught the attention of the Duncans and perhaps they wondered whether they had been bugged during the audit. This is speculation, of course, but it could account for Booner’s actions during a subsequent audit. When the IRS returned in September 1971 to launch an audit—and, unbeknownst to the bank, a criminal investigation—Edwin Duncan, Jr., became convinced that the bank was being bugged by the IRS. The source for the story is Marty Kaiser and I think it credible.

According to Kaiser, “In the early 70s a disheveled man wearing mismatched jacket and pant and tennis shoes showed up at my door.… It was Edwin Duncan (now deceased) owner and President/Chairman of Northwestern Bank head quartered in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina.” (Later context makes it clear that this was the younger Duncan, usually called Booner; he was not the owner of the bank, however, though he and his father were the largest single shareholders.)

According to Kaiser, Duncan “told me he was having security problems at his bank and was afraid the IRS was bugging him. I agreed to train his security officer, Jerry Starr (also now deceased), who in turn purchased a quantity of countermeasure equipment” (26). In Kaiser’s memoir, Duncan’s request for help is blunt: “‘The goddamned IRS is investigating me and I think they’re bugging the phones and the offices’” (27). One of Booner's obituaries supports Kaiser's story in a general way: Boooner is said to have "prided himself on having 'bugged' federal agents in the same manner that he had accused them of doing" (27a).

Kaiser continues:

“I showed Duncan the types of countermeasure gear that would be needed for the sweep and he wrote me out a check for them on the spot. …

Jerry Starr came to Baltimore the following week and spent a day with me learning how to use the equipment. But as so often happens, Starr was still not up to speed on how the equipment worked. About two weeks after his visit, he called and asked if I would come down to the bank and walk him through a sweep with the equipment.” (28)

Duncan sent a “a twin engine turboprop” to ferry Kaiser to North Carolina—no doubt courtesy of our old friend, Certified Check and Title—and then Kaiser and Starr swept about five buildings in the bank complex. They found two bugs—one in the office of the comptroller (when the office was unlocked, Starr found the bug in a hollowed-out Bible), and the other in “the main bank building….[,] a device that only the federal government would have had access to. Known in the trade as a ‘key / logger,’ it was a transmitter attached to the bank’s computer deigned to capture all of the bank’s financial data and confidential documents on the hard drive.” (29)

Assuming the story is accurate, there is no definitive way to know who planted the bugs and why, but the then recent revelations regarding the IRS, as well as the presence of IRS agents at the bank, would have naturally suggested their culpability. I wonder why Kaiser did not detect the bug planted in the IRS office. Perhaps he did but concealed it from his readers. Or perhaps he swept the building in early September 1971, before the bank's bug was planted.

Kaiser is not reliable with dates—many events that demonstrably occurred in 1977 are placed by him in 1978—so it is not clear whether his sweep of the bank occurred before or after the bank bugged the IRS office in September 1971. The issue never came up in Duncan’s trial. The defense did repeatedly try to establish animus by the IRS against the bank, but in vain: the judge quickly shut down those lines of questioning (30). Perhaps the lawyers were working up to a big “reveal”: perhaps they thought the revelation of illicit IRS snooping on the bank would discredit the government’s case and provide a justification for Duncan’s bugging (or counter-bugging) of the IRS. But, if such was their intent, they were never able to lay the foundation for the revelation. For example, in Duncan's trial for eavesdropping on the IRS, the judge would not let "IRS agent Carr answer a question as to whether 'he had ever used surreptitious monitoring equipment in any of his investigations'” (31), And, as I have said, Kaiser’s memoir, written years later, places the discovery of the bugs in 1972, after Duncan had already installed his own bugs. To accommodate all the events that Kaiser recounts--his hiring by Duncan, the selection and purchase of the equipment, the training of Starr, the two-week delay between Starr’s training and his request for help, Kaiser’s flight to North Wilkesboro, and the sweep itself--two or three months in 1972 is more likely than a single month in 1971.

Finally, Kaiser does not take credit for building or selling the bug planted in the IRS office in September 1971. As we have seen, he was not shy about taking credit for his work, so I don’t think Duncan obtained the bug from him.

Posted 3 April 2024, updated 8, 12, 13 April 2024. Please send comments, corrections, and questions to [email protected].

Martin L. Kaiser at work. Source: http://tscm.com/mlkvendetta.html

At some forgotten time, I imagined how an eavesdropping engineer might pitch his wares:

I’ve got a line of preamps

that pick up the slightest sounds--

one man sighing, another

cracking knuckles, the third

weeping in his hands.

At some forgotten time, I imagined how an eavesdropping engineer might pitch his wares:

I’ve got a line of preamps

that pick up the slightest sounds--

one man sighing, another

cracking knuckles, the third

weeping in his hands.

NOTES

Note 1: The title and the first two epigraphs of this part are from Brian Hochman, The Listeners: A History of Wiretapping in the United States (p. 175). Harvard University Press. Kindle Edition.

Note 2: Hochman is quoting Marshall McLuhan, “At the Moment of Sputnik the Planet Became a Global Theater in Which There Are No Spectators but Only Actors,” Journal of Communications 24, no. 1 (March 1974): 54.

Note 3: John Byrd, “Edwin Duncan, Former Bank Chairman, Dies,” Winston-Salem Journal, 7 Mar 1985, 1.

Note 4: The general discussion of electronic surveillance is largely based on Hochman, The Listeners. Other sources will be identified as appropriate.

Note 5: Brian De Palma, “The Making of ‘The Conversation’: An Interview with Francis Ford Coppola,” Filmmakers Newsletter, v. 7, no. 7, n.d., downloaded from Cinephilia & Beyond (https://cinephiliabeyond.org/francis-ford-coppola-brian-de-palma-conversation-two-great-filmmakers/).

Note 6: Brian Hochman, The Listeners, 108. The study was conducted by “Anthony P. Savarese, an assemblyman with connections to the New York City Anti-Crime Committee,” through “a joint commission on the illegal interception of electronic communications” authorized by the state legislature. Hochman summarizes many of the commission’s findings.

Note 7: Marty L. Kaiser, III, Odyssey of an Eavesdropper (Caroll & Graf, 2005), 5. Odyssey does not give Kaiser’s birthyear, but it was included in a draft of the book that was posted online some years ago in “FBI Vendetta Against Martin Luther Kaiser III.” The website still exists, but much of the information has been removed.

In trying to build the character of Caul, Coppola imagined that he was “one of those kids who’s sort of a weirdo in high school…. the kind of technical freak who’s president of the radio club,” so not unlike Kaiser. De Palma, “The Making of ‘The Conversation.’”

Note 8: Kaiser, Odyssey, 34-38.

Note 9: Odyssey, 39.

Note 10: For example, Michael T. Smith describes Lipset as the inspiration for Caul ("Not Privy to The Conversation: Harry Caul as a Peripheral Character in Coppola’s Film,” cinaction, May 2020 (https://cineaction.ca/issue-100/not-privy-to-the-conversation-harry-caul-as-a-peripheral-character-in-coppolas-film/)). Kaiser claims credit on his current webpage (http://tscm.com/mlkvendetta.html) and in his IMDB entry (https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0435187/bio/).

Note 11: Alex Markels, “Warrantless Wiretaps: A Guide to the Debate,” NPR, 20 Dec 2005 https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5061834). Markels credits Lipset as the inspiration for Harry Caul.

Example of news stories featuring Lipset’s demonstration: “How to 'Bug' a Room from Hawaii,” Buffalo News, 19 Feb 1965, 3; Jack Metcalfe, "The Tattletale Martini," New York Daily News, 5 Sep 1965, 66.

Note 12: Hochman, The Listeners, 175.

Note 13: Kaiser, Odyssey, xi.

Note 14: Kaiser, Odyssey, 213.

Note 14: Smith, “Not Privy to the Conversation”; Kaiser, Odyssey, 213.

Note 16: Joe Pichirallo, “Bugging Participation: Duncan Relieved of Charge,” Winston-Salem Journal, 3 Aug 1977, 1-2.

Note 17: Hochman, The Listeners, 109.

Note 18: Hochman, The Listeners, 126-127.

Note 18a: Conversation on 5 April 2024.

Note 19: Lou Panos, "Witness's Business Suddenly Drops," Baltimore Evening Sun, 25 Oct 1976, A11.

Note 20: Hochman, The Listeners, 146.

Note 21: The Listeners, 183-184.

Note 22: David Bailey, “Edwin Duncan Trial: Witness ‘Anguished’ by Bugging” (changed in a later edition to “Witness Says Bugging Bugged Him”), Winston-Salem Journal, 9 Sept 1977, 1-2. According to this story, the check was for $299,000, or almost $2.9 million in today’s money.

Note 23: Email to writer, 26 March 2024.

Note 24: John Byrd, “Edwin Duncan, Former Bank Chairman, Dies,” Winston-Salem Journal, 7 Mar 1985, 1.

Note 25: “Bullying Tactics in Probe Charged,” Winston-Salem Journal, 21 July 1965, 2.

Note 26: Kaiser, “FBI Vendetta Against Martin Luther Kaiser III”

Note 27: Kaiser, Odyssey, 87.

Note 27a: Bill East, “Banker Edwin Duncan Dies at 57,” Sentinel, 7 Mar 1985, 13, 16.

Note 28: Kaiser, Odyssey, 88.

Note 29: Kaiser, “FBI Vendetta” and Odyssey, 89-90.

Note 30: For example, Mark Wright, “U.S. Wanted to ‘Get’ Duncan, Lawyers Say,” Sentinel, 8 Sep 1977, 11, 12.

Note 31: David Bailey, “Tapes Indicate Bugging Suspected,” Winston-Salem Journal, 30 Sep 1977, 1, 2