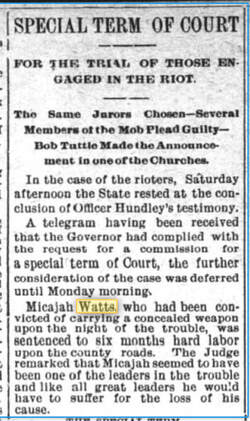

Micajah Watt (or Watts) was identified by the court as a ringleader in the effort to protect Tuttle. Can we find evidence of his leadership outside of the newspapers? (The article excerpt is from the Western Sentinel, 22 August 1895). Connections (3) – Micajah (Cager) Watt and the Depot Street School Neighborhood

Micajah Watt or Watts (1847/1849 – 5 May 1905. PID GS65-YPD). Watt was usually called Cager, but he was also shown in newspapers and elsewhere as Kajah, Cajer, Mc Cager, and possibly Kaziah. At almost 50, Watt was one of the oldest men arrested in the aftermath of the riot; born in 1850 or earlier, he was old enough to remember slavery times. An article in 1886 listed him as one of 68 African Americans in Winston-Salem who owned improved real estate (Western Sentinel, 11 March 1886). The judge at the trial of the rioters considered him a ringleader in the effort to protect Arthur Tuttle. As a ringleader, Watt received a sentence of six months of hard labor on the county road. This was the second most severe sentence handed down. It is possible that his sentence was no longer because of his age; in other cases, as I have noted, the court showed leniency on account of health or age. One of the three men who received longer sentences, Pleas Webster, was a much younger man, somewhere between 27 and 31 years of age, but I have not found evidence for the age of the two other men (Charles Hauser and Frank Robinson) who received a one-year sentence. As a reputed leader, Watt was also singled out for unofficial punishment—abuse while in prison. Although a cook and restaurant owner, he was made to work at hard labor rather than serve as the prison camp’s cook. He was whipped in the camp with the knowledge of, if not at the order of, the camp superintendent. We know this because of a short article on the front page of the Western Sentinel. It begins with a headline—“County Convict Camp. Micajah Watts Was Not Whipped”—that is not supported by the story: the story does not say that Watt was not whipped, but only that he was not whipped by Superintendent Shutt; in recent political jargon, it is a nondenial denial. Beating Watt was obviously meant to intimidate and bully him; placing the story on the first page and printing a denial that, in effect, acknowledged the beating were both consistent with a strategy of intimidating the community that looked up to Watt. But this is admittedly speculation. *********** My original goal in studying the protectors as a group was to ascertain whether Watt was, as claimed by the court and newspapers, a leader in the effort to protect Tuttle. Are there clues that justify the claims that he was a leader in the community? I thought I might find clues in identifying the men who lived near him. Cager Watt lived at 809 Depot St and ran a restaurant at 807 ½ Depot; the “Graded School” for African American children was not far away, at 615 Depot. The Depot Street school was a major institution in the African American community. Established in 1887, its principal from 1890 - 1895 was Simon G. Atkins; in 1895 he moved to take charge of the Slater Institute, forerunner of Winston-Salem State University, where he served for many years. In addition to the men arrested for riot (see below), many prominent citizens lived nearby, including Rufus Clement (801 Depot), an alderman and a member of the Republican Executive Committee; lawyer John S. Fitts (corner of Chestnut and E. 7th), who defended a number of the men arrested for riot; Dr. H. H. Hall, who lived at 127 E. 7th ; and Dr. J. W. Jones, at 710 Chestnut. Nearby institutions included the African American Hook and Ladder company commanded by Aaron Moore (E. 7th near Depot), who served at least one term as alderman. Just across the street from the graded school, on the corner of 7th, was the AME Zion church. If you walked from the corner heading west on 7th, on the right was the Hotel Bethel, the only hotel for African Americans in Winston-Salem. (Later, an important community center, the hall of the Knights of Pythias, was located here.) Just before the hotel, you could turn north on Chestnut and soon walk to the home of the Rev. J. C. Alston at 714, then to his church, Lloyd Presbyterian. Dr. J. W. Jones lived at 710, and few years later, the lawyer James S. Lanier would live at 713, near the Presbyterian church where he worshiped; like Fitts, he defended in court a number of those arrested for riot, including Pleas Webster. Webster lived nearby, at 715 E. 9th. Continuing on 7th, just past the hotel you could turn left on Chestnut and walk south a block to the First Baptist Church, near the corner of 6th Street; the pastor, the Rev. G. W Holland, lived at 309 E. 8th, within easy walking distance and a few doors down from shoemaker Wesley Mitchell, one of Tuttle’s protectors. Holland officiated at the weddings of Samuel Toliver, Walter Price, and Aaron Stone. From the hotel you could also continue west on 7th Street and soon reach, on the left, St Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church and the home of its minister, the Rev. W. W. Pope. Pope officiated at the marriage of Frank Meadows and Sam Penn. His church is likely where Robert Tuttle rose after the service on the evening of August 11, 1895, to ask the congregation to gather near the jail to protect his brother, Arthur, from lynching. *********** Given the vibrancy of the neighborhood, it is not surprising that many of its citizens would have acted to protect Tuttle. The information available cannot prove that Watt was a leader. But it is still interesting and possibly significant that between Watt’s business and the Depot St. school lived several men arrested for participation in the riot: William Cooper (724 ½ Depot St)—sentenced to pay proportion of costs. He may also have been known as Will Copper, and there may have been a white man in town with the same name. I have not found other connections for him. Calvin Martin (738 Depot)—indicted, but no information available on the disposition of case. Two men named Calvin Martin seemed to have lived in town at the time, close in age, but married to different women. The Martin on Depot St (born 1864 – 1869) married Mary Davis in 1891; the other (born 1872) married Paulina Mitchel in 1895. Both marriages persisted into the next century. Both men were working class. I don’t know which man was involved in the riot, but I suspect it was the older man. Matt Malone (728 ½ Depot)—discharged without payment of costs. Another Matt Malone—or perhaps the same man who moved while the 1894 directory was being prepared—lived nearby, at 330A 7½ St., the same address as Walter Price, found not guilty. I have not established other connections for Malone. Price was married in September 1894 by the Rev. G. W. Holland to Alice Holmes of Reidsville; I have found no other connections for him. Henry (W. H.) Neal’s home and grocery store were near Price, at 313 7½ St; he was found not guilty. He was politically active a few years later, in the hotly contested election of 1898. On one occasion, he and John Mack Johnson appeared to take the opposite sides in an acrimonious debate; in a later discussion, his words were construed (or misconstrued) by the local white supremacist newspaper to heighten racial tension. I will discuss politics in more detail later. James Williams (734 ½ Depot)—sentenced to 4 months of hard labor on the county roads. I have not established other connections for Williams. Other rioters who lived nearby on other streets include: Frank Carter (possibly the C. F. Carter who lived at 523 Sycamore St)—pleaded guilty, but because of his high character, was not sentenced to hard labor but fined $50 and his proportion of costs. Carter likely lived near the school, since he was employed there as a janitor—a salaried position that was highly coveted. He was licensed to preach by a local church (I don’t know which) and, like Samuel Toliver and James Dandridge, he belonged to the Knights of Pythias. He also employed tobacco stemmers. I think it quite likely that contemporary sources sometimes identified him by his initials. Most white men and certain African American men, primarily those accorded a degree of respect by the white community, were known in the newspapers by their initials—R. J. Reynolds, for example. African American ministers were regularly identified this way, for example, the Rev. G. W. Holland, minister at the 1st Baptist Church. Usage was not consistent. It is possible but not certain, then, that C. F. Carter was Frank Carter. Also living on Sycamore, at 608 was John Grogan, found guilty but released without fine, costs, or hard labor. Wesley Mitchell (315 E. 8th St)—not guilty. I have not been able to establish other connections for him. Aaron Stone (618 Chestnut St, just south of the Presbyterian minister and his church)—For unknown reasons, his sentence—three months at hard labor on the public roads—was changed by the judge to $50 and cost. I have not been able to establish other connections for him, except the fact the Rev. G. W. Holland officiated at his wedding. James Dandridge also lived on Chestnut St, at 253. He was sentenced to four months at hard labor on the county roads. As I noted in a previous post, there were later at least three men of this name in town. I do not know which of the men lived on Chestnut, nor which participated in protecting Tuttle. The oldest of the three seems to have been about the same age as Cager Watt; at his death in 1922, he was a member of the Masons, the Knights of Pythias (like Samuel Toliver and Frank Carter), and the Odd Fellows, in whose cemetery he was buried. *********** As with my previous posts, this is an interim report. There are a few known sources of inform I have yet to explore and perhaps better ways of assembling and understanding the information I have already gathered.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed