The Union Republican (23 May 1895) In 1880, Charles Tuttle (born around 1827) and his wife, Margaret (born around 1841), lived in Middle Fork Township in Forsyth County, a key part of the Black-majority Winston third ward from 1892 to 1895. Charles farmed (the 1900 census shows he owned the mortgaged farm), his wife kept house, and by 1880 some of the children were already working in factories, including Walter at the age of 12. Evidence gathered by Bertha Hampton Miller for her 1981 dissertation suggests that Charles Tuttle “had money and large land holdings which incited envy among many whites”; newspapers from the white and African American communities agreed that the Tuttle sons had “’unsavory reputations’” (“Blacks in Winston-Salem 1895-1920,” 46).

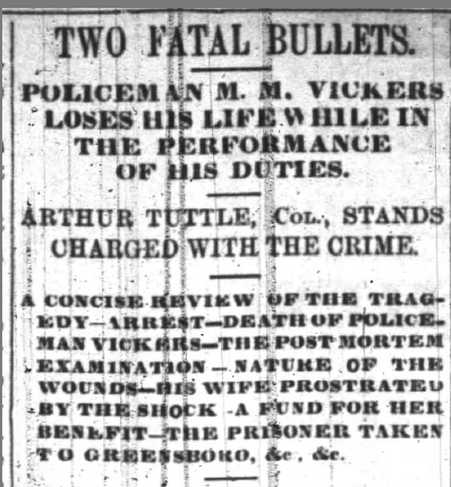

Five of their ten known children figure in the story—Ida, born in 1863; William, born in 1867; Walter, 1868; Robert, 1871; and Arthur, 1875. Until May 1895, Walter was the family member most often in the news. He was frequently in trouble with law, primarily for brawling (the actual charge was “affray”) and assault. So far as can be determined from the surviving newspapers, Walter reached a turning point in his life in March 1892. A drunk white man paid Walter, also drunk, and Sim Brannon to attack a young tobacco farmer from Rockingham County. The attack took place in the Piedmont Tobacco Warehouse. Farmer Nelson gave better than he got: he seriously wounded Walter with a knife and escaped without serious injury, as did Brannon. Chief of Police J. W. Bradford and Brannon sat up all night nursing Walter’s wounds. Tuttle was sent home to recover; before his trial he left town and went into hiding. He was not caught until December 1892. In March 1893 he was convicted on several counts of assault and sentenced to 12 months of hard labor on the county roads. He then disappeared from the Winston-Salem newspapers for about 14 months. In May 1894, Tuttle was arrested for assaulting Bradford, now the former chief, “probably on account of some old grudge because of Bradford’s course in some way against Tuttle during Bradford’s term of office as chief-of-police” (Western Sentinel, 26 July 1894). Possibly Bradford’s treatment of Tuttle for his knife wounds was not as benign as the newspapers reported. Even among his fellow officers, Bradford seems to have had a reputation for harsh treatment; a few years later, when the ex-chief was himself arrested, he accused the arresting officers of mistreatment. One replied, “D--- you, you have treated many a man worse than this for less offences” (Western Sentinel, 9 Dec 1897). Whatever the reason for his assault, Tuttle was convicted. Desperate to avoid another stint at hard labor—aside from the rigors of the prison life, he had a wife and two-year-old daughter—he asked Policeman J. R. Hasten to accompany him to find someone to pay the fine on his behalf. According to Hasten, when they were on the grounds of a tobacco factory, Tuttle tried “to snatch the pistol from [the officer’s] hip pocket, … and … failing in this grabbed” the officer’s billy club (Western Sentinel, 9 Dec 1897). The officer said he pulled his .38 and mortally wounded Tuttle. Eventually, witnesses came forward claiming that the officer had lied, that Tuttle had not gone for the his gun. Hasten was indicted for murder—the first indictment against a Winston-Salem police officer for killing an African American—and in May 1895 he was put on trial. But on Saturday, May 19, the white jury found him innocent. In the afternoon after the verdict, the sidewalks around the courthouse were as usual crowded with pedestrians. Among them was Arthur Tuttle, no doubt angry and upset by Hasten’s acquittal. He refused the orders of two policemen, Michael Vickers and Alex Dean, to move from the sidewalk to let others (probably white women) pass and became verbally defiant; he would move when he “damn got ready” (Union Republican, 15 Aug 1895). One of the policemen moved him from the sidewalk—it is not clear how much force was used—and Walter fought back. During the struggle, Tuttle grabbed a pistol (from his pocket or shirt or perhaps from the ground after it fell from his clothing) and twice shot officer Vickers. He was arrested on the spot; Vickers died the next evening. Fearing that a lynching would be attempted, African Americans gathered near the county jail. The authorities quickly moved Arthur Tuttle to Greensboro, then farther away, to Charlotte. He was returned for the trial in August, despite the request of the defense lawyers for change in venue. When the trial was in recess on Sunday, August 11, the white and black communities were swept by rumors of a gathering lynch mob. That evening, after church service, one of the Tuttle sons, Robert, asked a Methodist Episcopal congregation to take up weapons and gather near the church to protect his brother. In her memoir published just three years later, Ida Beard (daughter of a Confederate veteran) reported it as a night of rumor and fear, rumors that came to her from her husband, who worked in the office of a justice of the peace. To her disgust, he had helped in Tuttle’s legal defense and supported the effort to protect him from lynching. I have seen no evidence that Robert joined the men guarding Tuttle. The oldest Tuttle son, William, evidently participated and then fled to avoid arrest. He was arrested in Statesville at the end of November, but I have not found stories indicating that he was tried. Years later, eyewitnesses reported in interviews that “Tuttle’s sister, Ida, weighing about three hundred pounds, sat on the courtroom steps brandishing two six gun shooters, and warned whites who had gathered a few yards aways: ‘The first white man comes across her to undo this jail door, I’m gonna kill him’” (Miller, 45). Next posts: I will begin exploring the lives and connections of the men who gathered to protect Tuttle. Sources: In addition to Miller’s Duke University dissertation, I have used contemporary newspapers and Fam Brownlee’s very useful account, ”Murder, Rumors of Murder and Even More Rumors…” For a more detailed account, see Appendix C of my annotated edition of Ida Beard’s memoir, My Own Life. Like what you read? Please buy my books! Send questions and comments to [email protected].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed