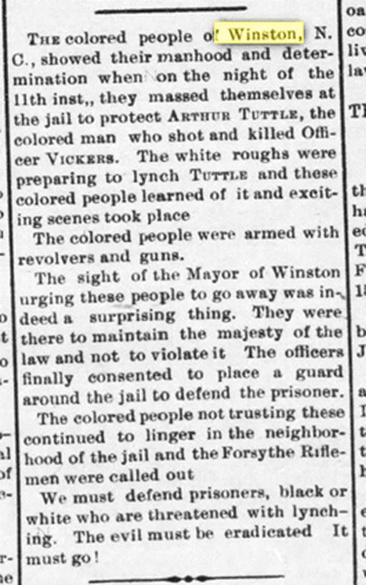

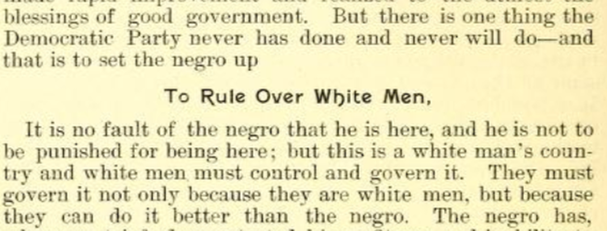

Richmond Planet (17 Aug 1895, 2) Perhaps the wisest words about the defense of Tuttle are from this item, probably but not certainly written by the editor, John Mitchell, Jr.: in preventing a lynching, Tuttle's defenders "were there to maintain the majesty of the law and not to violate it." One of Tuttle’s defenders, Samuel Toliver, was or shortly afterwards became the local agent for the Planet. He appears to have come to Winston-Salem from Richmond, and occasionally traveled to Richmond to confer with Mitchell. **** The Tuttle defenders in focus—Several of the defenders had modest political ambitions; that is, they had the American, if not human, desire to govern themselves and to represent a constituency: • In 1891, John Mack Johnson or someone with a similar name was on the Colored School Committee. • In 1892, Peter Owens was on the credentials committee of the county Republican convention, and in 1894 he was named as a delegate to the state Republican convention. • In 1896, Frank Carter was elected as a town alderman. • In 1898, John Mack Johnson (also spelled McJohnson) and Henry Neal participated in the campaign to select Republican candidates for the general election. Johnson sided with insurgents (the Rev. J. T. Gibbons and others), apparently angry that the electoral successes of 1894 and 1896 had not provided more patronage positions for blacks. • In the same year, Sam Toliver chaired a meeting of the Republican party in the 1st ward. • In October 1898, Neal gave a speech that touched on the relationships between black men and white woman. This was a hot topic in the campaign, as I will discuss in a later post. Neal’s speech was reported by a hostile source, The Western Sentinel, no doubt with the intent of keeping this issue alive. But we don’t know what Neal actually said—all we have is the brief quotation used by the Sentinel to inflame racist opinion. **** The situation in 1898--In upcoming posts, to provide the political background in which our fifty men acted to defend Arthur Tuttle, I will comment on two prescient letters to the Union Republican published in August and September 1898, in the run-up to the election. The anonymous writer was from Ruffin, NC, so I will call his letters the “Ruffin letters.” To understand these letters requires an introduction to the political situation in 1898. I know this is an odd way to proceed, but these blogposts are a very rough draft of the projected book, and I am writing about topics as they occur to me. During the isolation of the pandemic, my research made me increasingly aware of the tactics used by the Democratic Party in North Carolina to prepare the way for the formal imposition of Jim Crow in 1900. In the campaign of 1898, these tactics were out in the open. In the eyes of those living in North Carolina at the time, the imposition of Jim Crow—by which I mean the formal disenfranchisement of blacks (and poor whites, too)—was not inevitable. It’s too easy for us to suppose that, because it did happen, it had to happen. But it was not easy to achieve—it took the combined efforts of the white Democratic ruling class, propaganda by most of the newspapers in the state, the demagoguery of politicians (faithfully repeated in the newspapers), and the terror campaign by the Red Shirts, those direct lineal descendants of the KKK and the Gadarene swine. It was also suspected, then and later, that some well-known black leaders were bribed into attacking the Republican candidates and party. Newspapers helped the Democrats seize effective control of political language in the service of white supremacy. The rule by and for the white elites was called “the Democracy”; allowing Republicans to govern or blacks to vote was, by definition, anti-Democratic. Every means was justified to ensure triumph of “the Democracy,” much as demagogues in every epoch of our republic shout democracy while silencing dissenters. The meaning of “the Democracy” was made quite clear in the party’s handbook for the 1898 election:  The triumph of Jim Crow was also ensured by the feeble campaign mounted by the opposing parties, the Republicans and the Populists. The fusion of Republicans and Populists had enjoyed stunning successes in the elections of 1894 and 1896; those successes provided the immediate context to the defense of Tuttle in 1895. But by the election of 1898, the Fusion legislative agenda had been largely enacted, including measures to expand the franchise and ensure the integrity of the vote. Now Republicans and Populists differed on the way forward. They dithered and they bickered. As we will see in the Ruffin letters, their only shared campaign issue was opposition to the Democratic party. A more fundamental issue was social equality between the races. To some extent, white Republicans were willing to grant a degree of political equality to blacks, but they resisted social equality, particularly in any setting that brought black men into relations with white women or placed blacks in authority over whites. Only a courageous genius could have navigated those stormy straits. But white Republicans—reluctant to appoint their African American allies to lucrative patronage positions or elect them to higher office—were not courageous or generous, and all too were eager to find an excuse to abandon the backbone of the party. For they were also dunces. For example, in 1900, P. T. Lehman, a Republican justice of the peace in Winston-Salem, deserted the Republican governor to support the Democrats’ constitutional amendment limiting the black franchise. He thought that, by removing “the Negro question” from politics, the Democrats would lose their major political issue and their ability to win offices. But this was suicide wrapped in an illusion: there could be no important Republican victories in NC without black votes. Worse, it was a betrayal. Lehman died in 1924. Voting rights were not restored to blacks until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The next Republican governor was not elected until 1973. This then is the context in which the anonymous letter writer from Ruffin, NC, gave his prescient take on the political situation in late summer 1898. Updated 14 Sept 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed