Detail of a Late Archaic kylix (drinking cup), about 510-500 BC. Period: Archaic Greek. An octopus hiding from a fisherman. Source: https://twitter.com/archaeologyart/status/1464215491879260167/photo/1 One my harmless pastimes as a poet is to render prose translations of poems from the Greek Anthology into English verse. I worry more about creating a poem that pleases me than trying to recreate in English verse the formal properties of the original.

Julianus the Egyptian is thought to have served as Prefect of Egypt during the reign of Justinian, emperor of Byzantium, in the 6th century AD. He has seventy-one poems in the Greek Anthology. His work is considered derivative of earlier epigrammatists. The works in the anthology span the classical, Hellenistic, and Byzantine eras, more than 1200 years of literary. Settings, stock characters, themes, and images are frequently recycled by many of the epigrammatists. The Old Fisherman by Julianus, Prefect of Egypt (Greek Anthology, VI, 26) Cinyras dedicates to the nymphs this net; he can’t endure the labor of casting it. Little fishes, now you can swim at ease: the old man has given you back the seas.

0 Comments

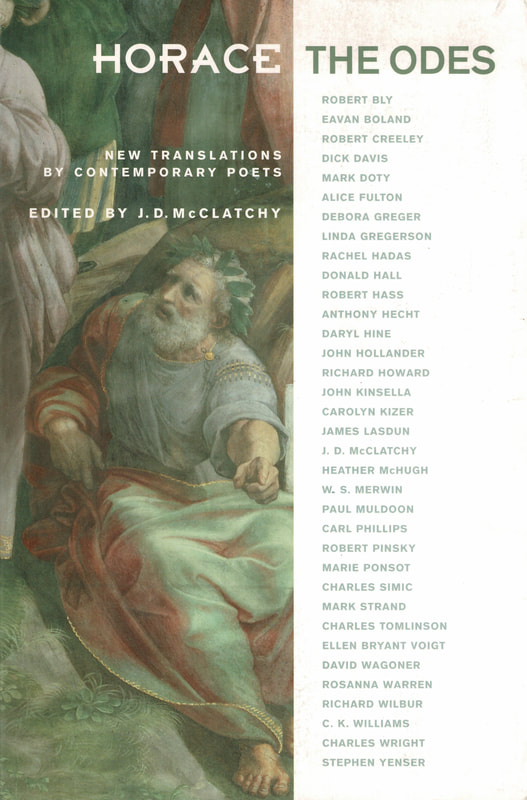

My favorite version of I.37, so far, is the translation by Ellen Bryant Voight: The translation was published in J.D. McClatchy, ed., Horace: the Odes (Princeton, 2002, p. 103), a volume well worth owning if you’re interested in the odes. Around thirty-five leading poets from the US, the UK, and Ireland were “specially commissioned” to write the translations (“Introduction,” 5). Voight's translation (see below) is a model of clarity and craft. The poem makes admirable use of alliteration (for example, "dizzy with desire and drunk," "the hawk harasses the helpless dove, / or the hunter the hare"). As the poem nears the conclusion, slant rhymes begin to point line ends, culminating in the long i sound that caps the last four lines. I.37, translated by Ellen Bryant Voigt

Now it’s time to drink, now loosen your shoes and dance, now bring around elaborate couches and set the gods a feast, my friends! Before, the time wasn’t right to pour the vintage wines, not while that queen and her vile brood of advisors, dizzy with desire and drunk on luck, were busy in deluded plots against us. What sobered her up was seeing her fleet on fire-- hardly a ship survived—nightmare she woke to sending her fleeing, flying, from our shores, Caesar at the oars in close pursuit-- the way the hawk harasses the helpless dove, or the hunter the hare in the snow-packed open field-- intent on dragging the monster back in chains. And yet the death that she resolved was grand: a woman who did not shrink from the drawn blade, who did not try to slip away and hide, she looked straight at the palace now in ruins, her face composed, and without blinking took into her arms the scaly venomous snakes in order to drink each drop of their black wine, and by that cup this woman of such fierce pride made the triumph hers: that she would die not as a slave, and not as someone’s prize. Edited 2 Nov 2023, 3 Feb 2024  The Berlin Cleopatra, a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC (around the time of her visits to Rome in 46–44 BC), discovered in an Italian villa along the Via Appia and now located in the Altes Museum in Germany. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cleopatra#/media/File:Kleopatra-VII.-Altes-Museum-Berlin1.jpg) The ode is among Horace’s most famous, in part because it brings us a contemporary view of a great historical moment, the defeat and death of Cleopatra. But it’s also appreciated because of its surprising shift in tone and point of view: the Romans’ “scornful opprobrium” of Cleopatra’s drunken self-delusions (David Ferry, translator, The Odes of Horace, 10) becomes admiration of her clear-eyed resolution at the end. “Now is the time to drink” is the governing conceit—the Romans' celebration of their victory over the queen drunk on her fantasies becomes Cleopatra’s metaphorical drinking in (conbiberet) of the asp’s venom. The Romans would humiliate her by parading her, a dethroned queen, in a grand triumph; but she chooses her own private victory.

According to Eduard Fraenkel (Horace, Clarendon Press, 1957, 158-161), Cleopatra was "the nation's most dreaded enemy"; and news of the capture of Alexandra and of her death a few weeks later brought joy to the people of Rome. Cleopatra was viewed as a prodigy (monstrum), wonderfully and horribly outside the ordinary. But once "the feeling of horror recedes..., admiration takes its place. At the end of the poem written to celebrate Cleopatra's defeat her greatness dominates over everything else." Here's David Ferry’s translation: At last the day has come for celebration, For dancing and for drinking, bringing out The couches with their images of gods Adorned in preparation for the feast. Before today it would have been wrong to call For the festive Caecuban wine from the vintage bins, It would have been wrong while that besotted queen, With her vile gang of sick polluted creatures, Crazed with hope and drunk with her past successes, Was planning the death and destruction of the empire. But, comrades, she came to and sobered up When not one ship, almost, of all her fleet Escaped unburned, and Caesar saw to it That she was restored from madness to a state Of realistic terror. The way a hawk Chases a frightened dove or as a hunter Chases a hare across the snowy steppes, His galleys chased this fleeing queen, intending To put the monster prodigy into chains And bring her back to Rome. But she desired A nobler fate than that; she did not seek To hide her remnant fleet in a secret harbor; Nor did she, like a woman, quail with fear At the thought of what it is the dagger does. She grew more fierce as she beheld her death. Bravely, as if unmoved, she looked upon The ruins of her palace; bravely reached out, And touched the poison snakes, and picked them up, And handled them, and held them to her so Her heart might drink its fill of their black venom. In truth—no abject woman she—she scorned In triumph to be brought in galleys unqueened Across the seas to Rome to be a show. (David Ferry, The Odes of Horace, p. 71. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition.) Edited, 18 Oct 2023; 20 Oct 2023; 18 May 2024. Comments? Send them to [email protected]  Source: https://downunderpharaoh.patternbyetsy.com/listing/507220168/egyptian-art-cleopatra-dressed-as-the This is the beginning of several posts, possibly nonconsecutive, on Horace's Ode 1.37, the famous ode on Cleopatra. I begin with the Latin text and a literal translation. I don't read Latin myself, except for the simplest sentences, so I will be relying on others' translation and scholarship.

Ode 1.37 Nunc est bibendum (https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Odes_(Horace)/Book_I/37) Nunc est bibendum, nunc pede līberō pulsanda tellūs, nunc Saliāribus ōrnāre pulvīnar deōrum tempus erat dapibus, sodālēs. antehāc nefās dēprōmere Caecūbum cellīs avītīs, dum Capitōliō rēgīna dēmentīs ruīnās fūnus et imperiō parābat contāminātō cum grege turpium morbō virōrum, quidlibet inpotēns spērāre fortūnāque dulcī ēbria; sed minuit furōrem vix una sospes nāvis ab ignibus, mentemque lymphātam Mareōticō redēgit in vērōs timōrēs Caesar, ab Italiā volantem rēmīs adurgēns, accipiter velut mollīs columbās aut leporem citus vēnātor in campīs nivālis Haemōniae, daret ut catēnīs fātāle mōnstrum, quae generōsius perīre quaerēns nec muliebriter expāvit ēnsem, nec latentīs classe citā reparāvit ōrās, ausā et iacentem vīsere rēgiam voltū serēnō, fortis et asperās tractāre serpentēs, ut ātrum corpore conbiberet venēnum, dēlīberāta morte ferōcior: saevīs Liburnīs scīlicet invidēns prīvāta dēdūcī superbō, nōn humilis mulier triumphō. Literal English Translation (from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Odes_(Horace)/Book_I/37, with revisions from the prose translation by Steele Commager, The Odes of Horace, 90) Now it is time to drink; now with loose feet it is time for beating the earth; now it is time to decorate the gods' sacred couch for Salian feasts, comrades. Before this it was forbidden to draw forth Caecuban wine from old stores, while the Queen-- still plotting mad ruin for the Capitolium and planning the destruction of the state with a foul herd of men shameful with disease—was wild with all sorts of hopes, and drunk with sweet fortune. But it diminished her frenzy when scarcely one ship escaped from the flames, and Caesar reduced her mind, inflamed with Mareotic wine, to true fear, as he flew from Italy with straining oars, as a hawk pursues tender doves or a swift hunter the hare on the plains of snowy Haemonia, that he might put in chains that monster of fate. Wanting to die more nobly, she did not like a woman tremble at the sword, nor repair to hidden shores with her swift fleet, but, having dared to see her fallen palace with a tranquil face, she bravely took to herself the harsh-scaled serpents and drank in their black venom with her whole body, in her chosen death growing fiercer. Unwilling to be taken away by Liburnian warships, no humble woman, she scorned to be led as a private citizen, a captive in our triumph. Updated with photo, 18 Oct 2023. Send comments to [email protected] |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed