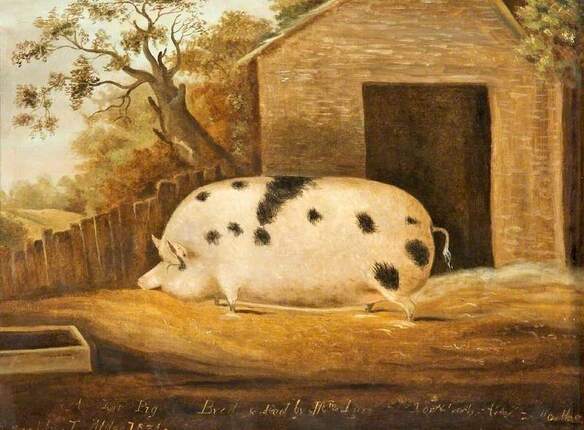

"Gloucester Old Spot," John Miles (active 1811-1842. Photo credit: Gloucester Museum Service Art Collection Not my best poem, perhaps, but one of my favorites, as it invokes love of language, plants and animals (especially the pig, of course), and my wife. And it teaches a thing or two about thank-you notes, too. It's included in my book Mouth Work, available directly from me (send an email to [email protected]) or from Amazon.

How to Write a Thank You Note Every gift, however trifling, should be acknowledged. —Lillian Eichler Watson, Standard Book of Letter Writing (1948, 1958) Beginning my song of thanks as big as the world: alleluia! For these I am thankful: for cara-rayada and mirikina, for schmalschnauzige and potto and cuchumbi, and for all milky plants, dandelion, milkweed, and sow-thistle: shushuk! bhulan! For names that make me laugh—chickwittles and pig-sty daisy-- I praise God in brief and simple words: safi! umununi! For plants that grow on roadsides and beautify dumpsters and for those called common—mallow, chickweed, mullein (for I too am common)—I give thanks, as I do for the victuals the wild swine eat—oak mast, prickly pear fruit, and leopard frog. Selah. I am grateful for the devourers, boar and barrow, gilt and sow. For piglet and shoat I sing this hymn of thanksgiving and instruction: O feral hog of Arkansas, O mulefoot from the Mississippi, write the letter quickly, while the glow is still with you! O snuffle-snout and nose-plow, the words will come of their own accord! You bacon- and chitterling-maker, it’s more gracious to mention the gifts, the sowbread, grub and fawn, for which you give thanks. For khuk and budur, for the moon in her cirrus boa whose silvery snout roots up the truffles of the stars, who sweet-cures the dreams she sends to my beloved, I will always give thanks. Scham-scham! Zizel and susel! Hallelujah! from Mouth Work St. Andrews University Press (2016)

0 Comments

Now we are in a position to understand the Ruffin letters published by the Union Republican on the 8th and 15th of September. The previous posts that have brought us to this point are:

• "'Pluck Enough': The Story So Far • "'Pluck Enough': An Introduction to the Background: Suicide Wrapped in an Illusion" • "'Pluck Enough': A Note on Methodology The letters are important, I think, because they end up predicting an event very like the Wilmington coup that happened just three months later. They also betray a blindness to the weaknesses in the Republican-Populist fusion, and an even greater blindness to the dissatisfaction among many African Americans, the most important Republican voting bloc. The anonymous writer assumes that the reader has a working knowledge of political history in the state since the end of the Civil War, and often alludes to events rather than specifying them; in my notes [inserted in boldface and set off by brackets], I try to help the current reader understand his allusions. I have added paragraph breaks to divide long stretches of text. **** Mr. Editor: By your indulgence, I wish to set before Republican and Populist readers an analysis of the Democratic plan of campaign in this State. As in physics, the amount of resistance to be overcome will gauge the effort and suggest the means to the end, so in politics. To appreciate the effort and means to be resorted to by Democrats to regain power in this State, it is only necessary to reflect that the position of the party is the most desperate that it has been for twenty years. During the long years of Republican rule in the nation, the Democrats felicitated themselves on the fact that they “held Robinson” [sic] and “saved the State.” With their advent to power under Cleveland [1st term began in March 1885] and the State still “safe,” their cup of joy ran over. With appetites whetted for official pie under two national administrations, and the long lease of power in the State, they were intoxicated with the belief that their joy could never end. [“Held Robinson [sic] and saved the state”—In 1875, a special election was held to elect delegates to the state’s constitutional convention. The balance of power in the convention came down to the vote in Robeson County. The phrase, “hold Robeson [County] and save the state,” was part of a telegram sent by the NC Democratic chairman to officials in Robeson County. It became proverbial for Democratic efforts to win elections at all costs. The Democrats ended up with a one-vote advantage in the convention, and they used it to pass a constitution that enabled them to dominate elections for 20 years. For example, it enabled “the undemocratic County Government Act of 1877 [that allowed] Democrats [to] maintain power over local governments. The law allowed the legislature to appoint local justices [previously elected at the local level], and permitted these appointed judges to choose county commissioners [who before had been elected in the county].” In other words, a majority of white Democratic legislators could prevent jurisdictions with majority Republican and Black voters from electing the most important local officials. “The law helped maintain Democratic control of ‘purse strings’ and prevent blacks or Republicans from gaining local power” Ronnie W. Faulkner, "Fusion Politics" (https://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/fusion-politics/).] With this sense of security and independence, there was fostered the already existing spirit of intolerance and bigotry that would brook no interference with opinions or policies eminating [sic] [from] this self-constituted oligarchy. This was the position of the bossesses [sic] and so-called leaders. The position of their constituency[:] Having had their fears, prejudices, and resentments appealed to, and played upon, for twenty years [the 20 years that preceded Cleveland’s term, i.e., since the end of the Civil War], they had been reduced to a condition of political starvation. I apprehend that if the average Populist were interviewed as to his reasons for leaving the Democratic party, he would reply that he was interested in certain reforms which his party spurned, and therefore was driven to go into a new party. In my opinion, this is merely a surface reason, the fundamental cause being that he was suffering the pangs of a slow form of political degeneration. Having been fed for so long, on the husks of hate, a change of diet was absolutely necessary to his political existence. Hence, a formidable revolt within the Democratic party of its most conservative element—the great middle class. Let it be understood that the essence of the Democratic position for all these years was, and is now, based on hatred and false pretenses. [para break added] The essence of the revolt within its ranks was based on a demand for a cessation of the campaign of hate, and a return to the discussion of principles and policies in the interest of the public good, and in this sense, patriotic. The means resorted to suppress this revolt are too fresh in the public mind to require elaborate statement. Suffice to say that the weapons of denunciation, proscription and ostracism wielded with such disastrous effect against Republicans were turned against their own late allies, and stuck fast in extreme cases, with ancient and malodorous eggs. [The weapon turned “against their own allies” was the Democratic legislature’s repeal of the charter of the North Carolina Farmers’ Alliance after the election of 1892. Rather than acceding to some of the populists’ demands, the Democratic legislature repealed the charter to punish populists for denying an absolute majority of votes for the Democratic candidate for governor (see Faulkner, “Fusion Politics”).] [para break added] This reform element, the great middle class, the bone and sinew of the Democratic party had not proceeded far in the advocacy of their principles before they saw the necessity for the organization of a new party, which assumed the name Populist. They had not proceeded far as a party before they realized that certain foundation work was necessary in order to give them even a fighting chance for final triumph; and while differing radically from Republicans in many particulars they found themselves in line on certain fundamentals to both parties, and hence, resulted in an alliance of both for the purpose of securing local self-government, a free ballot and fair count [i.e., to secure the electoral reforms passed by the fusion legislature after the election of 1894]. The people for once refused to heed the incendiary appeals to the worst part of their natures, and the result was overwhelming and disastrous defeat for the Democracy, the heroic self-sacrifice of Josephus Daniels [editor of the Raleigh News and Observer] to “save the State” to the contrary notwithstanding. While the bosses were stunned by the blow, and what was left of the rank and file were demoralized, they were not without consolation—they still had the presidency [Cleveland’s second term] and a goodly number of fat federal offices as well as the State government for two years. During the interim preceding the presidential and State campaign, Democratic parties fairly bristled with denunciations of the late Fred Douglas [sic] legislature, and a Democratic campaign hand-book was promulgated roasting the aforesaid legislature, when lo! the exigences of the campaign required a change of tactics. Free silver had become the national slogan, and Democratic-Populist fusion was in the air. Even Marion Butler, the arch conspirator in the frustration of Democratic machination was not such a bad man after all, in fact to the contrary he was a very nice gentleman. So from vinegar and red pepper there was a change to molasses and soft soap. Firery [sic] denunciations of the Populists was changed into cajolery. [para break added] While this change of tactics proved a death blow to the Democratic literature in that it required the suppression of the campaign hand-book, ventilating so-called Republican-Populist incompetency and misrule, and chock full of much other useful knowledge, the leaders, as usual, rose to the emergency, and henceforth that valuable book had to depend for circulation on the uncertain medium of Republican speakers. With a ccompaign [sic] of compromise not even the witchery of free silver and the disaffection of prominent Republicans and Populists within the ranks of their respective parties could “save the State.” This [i.e., the election of 1896] was defeat number two, humiliating and exasperating, embracing not only loss of the State government, but the presidency [Republican William McKinley succeeded Cleveland], wholesale loss of Congressmen, and nearly all the district and county governments with consequent loss of both federal and State patronage. [In the 54th Congress, NC was represented by 6 Republicans and Populists, and 3 Democrats; in the previous Congress, the Democrats had held 7 of the 9 seats. Similarly, in the General Assembly, the fusion of Republicans and Populists held 94 of the 120 seats, and in the Senate 43 of the 50 seats; in the previous General Assembly, the Democrats had held 93 of the 120 seats in the House, and 47 of 50 seats in the Senate.] [para break added] To perceive the straits of the Democratic party at this juncture, it is necessary to realize that it had been stricken in its most vital parts. The right to hold all the offices, or at least all the best, had come to recognized as among the inalienable rights, not that they loved office above other men, for as nature abhors a vacuum, so the average Democrat abhors office; but that in the lofty spirit of self-sacrifice, they simply hold the offices and received [sic] the perquisites in order to dignify the office, and keep them out of the profane hands of the so-called lower classes. So when the people lay their sacrilegious hands on affairs, and turned these gentry out to graze[,] their refined sensibilities were shocked. Stunned by defeat, their Spanish pride mortally wounded [an allusion to the Spanish-American war, then under way], they are now out in the wilderness of want and hunger, their appetites tantilized [sic] by the sight of others feeding from the green and luxuriating pastures from which they have been driven thirsting for revenge; and with “the end justifies the means” as a working principle, what will they not do to get it back? The history of the past supplies the answer. The leaders bewildered by two successive defeats having returned to partial consciousness without regaining the ability to think logically; and thinking vaguely that there must have been some connection between their former cry of negro domination or white supremacy, and their long lease of power in the State have resurrected that corpse to do duty in this campaign. Having lost on the field of legitimate discussion they return to the epithet as a weapon, and herein is that true proverb illustrated: “The dog is turned to his vomit again, and the sow that was washed to her wallowing in the mire.” The Democratic party of this State not having now a victory since the war except through appeals to passion and prejudice, neither learning nor forgetting, and incapable of addressing itself to the progress of events, will make the effort to regain power on the hypothesis that it can deceive the people by methods which they [the people] have repudiated with their eyes wide open. Having taken so much space to elucidate the present position and purpose of the Democracy, I shall have to defer to another issue the discussion of the plans for carrying their purpose into execution. Rockingham, Ruffin, N.C., Sept 2, 1898. A few days before Halloween, a coworker brought her eight-year-old daughter to my wife’s workplace dressed as a gardener. In a reverse trick-or-treating, the girl walked through the office handing out flowers. Patti brought three home and placed them in a vase in the sunroom. A couple of days ago, a stray beam of afternoon sunlight worked its way through the trees in the park behind our house and lit up one of the blossoms. For once, I was quick enough with the camera phone to capture the moment. I’ve had more trouble getting a picture of the goose among the ducks; maybe this one will do. Perhaps because I was busy in my yard, this year I didn’t encounter at our pond the gangs of ill-tempered geese protecting their goslings. Their season came and went without my notice, and now they’re gone, except for this lone goose which has been paddling with the mallards.

Look closely on the surface of the water and you’ll see a flotilla of pine needles. The pines have been shedding like a long-haired cat in July. Yesterday they were covering our cars, the parking pad, and the flower gardens, but not many seem to have fallen overnight. 10 a.m. Corrected 6 Nov 2023. Please send comments to [email protected]  Recently I exchanged books with Ethan Unklesbay, a poet I’ve not met in the flesh but whom I’ve encountered in a Facebook group. He runs a Substack site, (Almost) Daily Mormon Poetry, where he just published a brief appreciation of my chapbook, Night Weather. Our projects are similar in some respects. Both are self-published and both are tied to online projects. In his case, many of the poems in Dust have been or will be published on his Substack; in my case, the poems came from my early, happy days on Twitter, beginning in December 2008. (For those who are curious, I left it years before Elon Musk took over.) The comments below are expanded slightly from comments I sent to Ethan. Please direct comments and questions to [email protected]. "Pluck"—This poem is an imaginative take on a New Testament injunction, to pluck out the offending eye, and on the healing offered by Christ. The poem is amusing—the plucked out eye, let loose on the world, “Rolled under open skirts—and gritty: “He climbed into my eye socket, / Got down on his hands and knees, / And scrubbed.” It ends with the warmth of healing love. "The death of a scientist"—The poem is amusing and imaginative; it reminds me a bit of C. S. Lewis. I like the phrase "malleable light"—a fine way of evoking the differentness of reality for the dead. The scientist has a severe case of déformation professionnelle (a phrase I was taught by student at the University of Poitiers early in my mission) that keeps him from understanding the grand possibilities of being dead: “He was in the middle of testing his fifth / Spirit World Hypothesis.” The poem reminds me, in a good way, of Scott Hales’ book,. Hemingway in Paradise. "I'm sorry I didn't know...."—The dominant metaphor—a brain aneurysm is likened to a gunshot wound to the head—is startling and effective. After that, the three concluding lines stranded on the following page seem anticlimactic, but do provide a needed ending. "Carmody Sagers"—I like how Ethan handles the syllabic lines—the three line stanzas have four syllables in the first line, six in the second, and two in the last line. The poem handles the near-cliches of Christian imagery in a fresh, understated, emotionally genuine way. Ethan is offering his chapbook for $5, including postage. The best way to get in touch with him is through his email, [email protected]. The quickest way to access his poems is to follow him at ethanunklesbay.substack.com. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed