Allegorical depiction of the Roman goddess Abundantia with a cornucopia, by Rubens (ca. 1630). Public domain.From the Google Art Project. As I’ve noted here before, near the end of his life, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote many short poems in French. I find them challenging to translate; I feel as if I’m tramping through a China shop in muddy boots three sizes too large.

I’ve struggled with “Cornucopia” on and off since around 2009. For myself, I’ve come to regard it as a gloss on the familiar language in Malachi 3:10: God will open “the windows of heaven, and pour you out a blessing, that there shall not be room enough to receive it,” a sensation I often experienced in the months after returning to the church. The third stanza is key: if our hearts are already full, the plenty pouring out of the horn will appear as an incessant attack. In the final couplet, the symbol of the hunting horn suggests the attack is intentional, part of the miracle of plenty. As to what Rilke was thinking, the poems begins with a question about the origin of the horn, and the last couplet is ambiguous at best: while English heaven first summons the idea of a divine beyond, and secondarily the sky, French ciel works in the opposite way, I think. Cornucopia by Rilke O beautiful horn, from where do you lean into our hope? Being only the slope of a calyx, pour out flowers, flowers, flowers that, falling, make a bed bursting with the roundness of fruits fully ripened. And it all without end attacks us, a sudden onslaught to punish our insufficient, already full heart. O outsized horn, what miracle by you is given? O hunting horn sounding all things with the breath of heaven! Please direct comments and questions to [email protected]

0 Comments

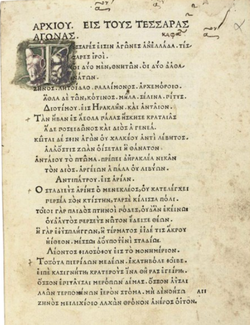

GREEK ANTHOLOGY -- Anthologia Graeca Planudea, in Greek. Recension by Maximus Planudes (c.1299), edited by Janus Lascaris (1445-1535). Florence: Laurentius Francisci de Alopa, 11 August 1494. (https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-greek-anthology-anthologia-graeca-5370940/?) The Greek Anthology is a rich collection of Greek poems, mostly epigrams, from the earliest poets through the Byzantine era. Many English translations exist for large parts of the anthology, so I’m exploring no new ground.

The poems here are all drawn from Book VI. It contains votive poems, described by David Ferry in his notes to Horace’s ode i.5, as “’dedicatory epigrams,’ in which representatives of various occupations—farmers, soldiers, artisans, musicians—deposit the tools of their trade in the temples of the appropriate gods.” In my observation, this is when the worker is retiring or nearing death (usually the same event). My translations are not independent treatments of poems in a language I cannot read, but the versification of English prose translations. The poems are presented in reverse chronological order, except for last; I cannot find dates for the final poet. The Boar Paulus Silentiarius (died AD 575–580) (VI, 168) The boar that rooted up the vines, and wallowed among the nodding reeds, whose tusks slashed the olive trees and put the sheepdogs to flight-- Xenophilus fought it with the sword when he found it by the river, teeth snapping, razorback bristling, breath smoking like burning wood, and on Pan’s tree he hung the hide. The Sailor Macedonius the Consul (500 – 560 AD) (VI, 69) Crantas, after many voyages, anchors his boat on the temple floor and dedicates it to the god of the seas. It no longer cares which winds ruffle the deep, for it sails the solid earth where poor Crantas stretches out to sleep. The Blacksmith Pancrates (ca. 140 AD) (VI, 117) To Hephaestus, the smith surrenders his pliers and tongs his five-pound hammer battered from beating iron, and the anvil he pounded, for with them he saved his children from living poor and dying starved. Leontichus Leonidas of Tarentum (3rd century BC) (VI, 205) On giving up his calling, the carpenter sets his tools aside—the grooved file, the wood-chewing plane, the ochre-stained rule, the hammer that strikes at both ends, the line and ochre-box, the drill-box and rasp, the heavy axe and handle that govern his craft, his revolving auger, and his faithful gimlet that turns in wood. Everything the man has used for fifty years, including his best screwdrivers and his double-edged adze, he gives to Athena, for she gave grace to all he did with the strength of his hands. On a Mother Dead in Childbirth Diodorus of Sardis (dates unknown)(VI, 348) These letters, written by Diodorus, say I was engraved for Athenaïs, dead in child-birth bearing a boy; and I weep to hold the daughter of Melo, who left in tears the women of Lesbos, in tears her father, who misses her most; Artemis would not hear me, bound on hunting the doe with her baying hounds. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed