There's no moment between human beings that I cannot record.

—Bernie Moran in Francis Ford Coppola, The Conversation (1)

—Bernie Moran in Francis Ford Coppola, The Conversation (1)

Part 8 - Guilt [Draft 1]

The IRS Comes Back to Town

At the age of ten, Martin Kaiser was building radio-controlled model planes and his first ham radio; not long after that age, Francis Ford Coppola was planting microphones around the house in the hopes of overhearing conversations about his Christmas presents. At that age Daddy was otherwise engaged: my brother and I “were 10 and 11 year old men doing all the work from spring plowing to getting in the crop. The horses were big, I would lead a horse up to the porch and together we buckled the harness on. My brother, being bigger and stronger, handled the plow and I drove the horses to pull the plow and turn the land over. The land was full of roots, rocks and stumps. When the plow hit a solid object it jumped out of the ground. Which meant stopping the horses backing them up and my brother pulled the plow back and we started up again. As the day wore on we would become literally exhausted and tempers wore thin. The plow hit a rock and it was my fault as naturally I put the rock or stump in place. We would cuss, fight, play and cry until quitting time and go home to a supper of cornbread and cold milk.”

Despite this unhappy picture, Daddy grew to enjoy hard manual labor and reveled in his capacity for it. Business was for making a living. But if Daddy did not have the typical background of a wiretapper and eavesdropper, in “Bugging the Buggers” we have seen that, under the direction of Booner, he became involved in planting bugs to surveil an employee suspected of embezzling and once brought home the equipment to show off to the family.

In September 1971, the IRS arrived at the headquarters of the bank in downtown North Wilkesboro to open another audit as well as a criminal investigation. Based on prior interactions with the IRS—a payment of over $200,000 in unpaid taxes that had been triumphantly recouped by the bank in 1966—Edwin Duncan, Jr., was convinced that the IRS was out to “get” the bank. As discussed in “Bugging the Buggers,” Booner (as Duncan, Jr., was universally called) had five bank buildings swept for listening devices and found two, including a sophisticated device that probably only the Feds would have access to. But this did not happen until 1972, according to Marty Kaiser. Back in September 1971, Booner decided to bug the office assigned to the IRS. We know some of the details because, six years later, in September 1977, at Booner’s trial, Daddy testified for the prosecution as a “surprise witness.”

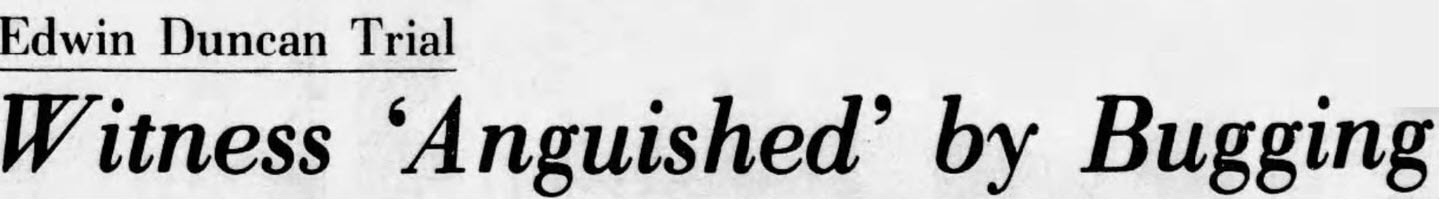

The following account is drawn from several newspaper accounts of his testimony as well as the summary of the facts of the case by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. My account includes direct quotation, paraphrase, and summary of the sources (see Note 2). Daddy was deeply troubled at the time he testified and had to be led into court by an FBI agent (I will describe his emotional state in the next part of my narrative), but he testified in a firm, clear voice.

Eavesdropping on the IRS: Daddy Testifies

In September 1971, Daddy was called to Duncan’s office; Duncan “told me he had the transmitter.” He and Duncan went to Winston-Salem the same day to buy batteries for the transmitter. (We have seen that Daddy and Booner had used mics and transmitters before, so none of this activity would have been unusual.) Around 10 p.m., he and Booner went to the bank headquarters building. They took the batteries, tapes, tools, and radio transmitter to the third-floor office assigned to the IRS agents. Daddy drilled a hole in the ceiling with his pocketknife—he carried a knife wherever he went, much as I always have a mechanical pencil. In its summary of the case, the appeals court noted that the IRS had been issued keys for the office, implying that the door of the office was likely locked that night. Daddy then went into the bathroom next door to the office and climbed into the attic space above the IRS office. Duncan handed him the transmitter and “I proceeded to put it in place.”

Daddy placed a microphone about the size of a nailhead over the hole he had drilled in the ceiling. Booner wanted to test the system, so he went into the board room with an FM receiver while Daddy waited in the IRS office. “I counted from one to ten, and he hollered down the hall that it was coming in loud and clear.” He and Duncan then cleaned up the IRS office, Duncan wiped fingerprints from the inside and outside office doorknobs, and they left the bank about 11:30 that night.

Later, Daddy changed the transmitter batteries at least once. His testimony on this point was consistent with earlier testimony by Jerry Duncan, Jr. (no relation to Booner), who said that he had changed the batteries and, more important, monitored and recorded the agents’ conversations at Booner’s request. Based on the testimony at the trial, Daddy did not participate in monitoring the conversations; by the time of the trial six years later, the planting of the bug was outside the statute of limitations. (2)

Aside from Jerry Duncan and Daddy, two other bank employees were named as unindicted coconspirators, the personnel officer and a senior vice president in the consumer loan division. (3) I don’t have much information as to what these men went through, but from trial testimony we so have the perspective of the IRS agents. They used the office on the third floor of bank headquarters until January 1973, when they moved offsite, in part because they suspected they were being bugged. Agent Owen T. McCusker testified he “was conducting a criminal investigation of Duncan and Certified Check and Title Corp. at Northwestern in 1972” (4). McCusker testified that “the agents had attempted to keep the exact nature of their examination of the bank confidential and that even the bank employes interviewed did not know what the investigation was about” (5). McCusker and other agents:

“suspected that their conversations were being monitored…, according to testimony and tape recordings played yesterday at the trial of Edwin Duncan Jr…. [D]efense attorneys questioned Owen T. McCusker, a retired IRS agent, about a search of the third-floor office agents were using at the bank’s headquarters. McCusker said that agent Phillip Johnson even got up on a chair and looked into a ventilator…..

“‘In fact,’ McCusker told the jury, ‘I checked myself (for a bug). I looked at the telephone. I looked for wiring.’ But McCusker said that after finding nothing, he gave the matter little thought.” (6)

Whether Booner or his coconspirators learned anything of use to them is not clear; in the next part of the memoir, I will speculate that the IRS conversations about Certified Check and Title put the spotlight on Daddy. Since he was a key participant in CC&T’s operations, at some point they began to wonder whether he would stay mum or betray them, his friends and employer.

Eight years later, in Booner’s obituary, his daughter claimed the taping wasn’t a secret: “‘Daddy was very proud about bugging the IRS, because this was war,’ [she] said. ‘He carried the tapes open around North Wilkesboro and joked about it.’” I infer from her words that the fact of spying on the IRS was the point, more important than any information that might have been gained (7). According to the testimony of Jerry Duncan, Booner eventually lost interest in the project, though it continued for as long as the agents were located inside the bank (8). Though he was a vice president of installment loans, Jerry Duncan testified that the monitoring and recording the conversations was “his every day thing”— apparently his main activity every day (9). I should think it a demoralizing chore, especially once Booner lost interest.

Planting the bug changed Daddy’s life forever. For me, it is hard to separate the story of the bugging from the story of Daddy’s emotional deterioration between the time of the bugging and his testimony, the topic of the next part and, like at least one of my siblings, memories of these events are almost inseparable from Watergate.

In his testimony, Daddy said that he “soon suffered ‘mental anguish’ because of ‘the fact that I had violated the law,’” presumably meaning the anti-eavesdropping provisions of a 1968 federal law (the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act). “He said that ‘as soon as I realized what I had done, I started to see my doctor,’” presumably Dr. Taylor. He couldn't sleep. Soon he began taking pills prescribed by the good doctor. He stopped doing any banking business in November 1971. “Absher had been a vice president in charge of public relations. ‘After we planted the bugging device I went over on the hill and worked at manual labor. . . . I helped put in a sewer line over there . . . and I just let my public relations job go more or less to hell.’” (10)

September 1971 - August 1976

In September 1971, the month that Daddy bugged the IRS, I was preparing to leave on my mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I was working at the bank in the Time Payment Department, an area within Jerry Duncan’s scope of responsibility, though I don’t remember ever meeting him or even hearing his name. I was oblivious to Daddy’s drama. September was also the month in which the White House “Plumbers” illegally searched the office of the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg, hoping to find information to discredit him. Ellsberg was a whistleblower who had leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and other newspapers. Officially titled The History of U.S. Decision-Making in Vietnam, 1945–1968, the papers revealed the deceptions and lies behind the U.S. war effort in Viet Nam (11). It was a major story at the time; Ellsberg, one of the authors of the study, was indicted for “stealing and holding secret documents” (11), but the charges were dismissed once the burglary in September 1971 came to light. Ellsberg had discovered, as my father was soon to find out, that whistleblowers are not popular with the powers-that-be.

In November 1971, around the time Daddy stopped doing banking business, I headed to Utah for a few days at the old Mission Home in Salt Lake City then several weeks at the Language Training Mission on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo.

Around Thanksgiving, I was struggling. At first I did not adapt to the new environment with its high expectations. I wrote a rather whining letter to Daddy, essentially asking permission to come home. (That was the gist, but I haven’t found the letter in my mission memorabilia.) Daddy answered wisely, giving me the out if I wanted it.

At the age of ten, Martin Kaiser was building radio-controlled model planes and his first ham radio; not long after that age, Francis Ford Coppola was planting microphones around the house in the hopes of overhearing conversations about his Christmas presents. At that age Daddy was otherwise engaged: my brother and I “were 10 and 11 year old men doing all the work from spring plowing to getting in the crop. The horses were big, I would lead a horse up to the porch and together we buckled the harness on. My brother, being bigger and stronger, handled the plow and I drove the horses to pull the plow and turn the land over. The land was full of roots, rocks and stumps. When the plow hit a solid object it jumped out of the ground. Which meant stopping the horses backing them up and my brother pulled the plow back and we started up again. As the day wore on we would become literally exhausted and tempers wore thin. The plow hit a rock and it was my fault as naturally I put the rock or stump in place. We would cuss, fight, play and cry until quitting time and go home to a supper of cornbread and cold milk.”

Despite this unhappy picture, Daddy grew to enjoy hard manual labor and reveled in his capacity for it. Business was for making a living. But if Daddy did not have the typical background of a wiretapper and eavesdropper, in “Bugging the Buggers” we have seen that, under the direction of Booner, he became involved in planting bugs to surveil an employee suspected of embezzling and once brought home the equipment to show off to the family.

In September 1971, the IRS arrived at the headquarters of the bank in downtown North Wilkesboro to open another audit as well as a criminal investigation. Based on prior interactions with the IRS—a payment of over $200,000 in unpaid taxes that had been triumphantly recouped by the bank in 1966—Edwin Duncan, Jr., was convinced that the IRS was out to “get” the bank. As discussed in “Bugging the Buggers,” Booner (as Duncan, Jr., was universally called) had five bank buildings swept for listening devices and found two, including a sophisticated device that probably only the Feds would have access to. But this did not happen until 1972, according to Marty Kaiser. Back in September 1971, Booner decided to bug the office assigned to the IRS. We know some of the details because, six years later, in September 1977, at Booner’s trial, Daddy testified for the prosecution as a “surprise witness.”

The following account is drawn from several newspaper accounts of his testimony as well as the summary of the facts of the case by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. My account includes direct quotation, paraphrase, and summary of the sources (see Note 2). Daddy was deeply troubled at the time he testified and had to be led into court by an FBI agent (I will describe his emotional state in the next part of my narrative), but he testified in a firm, clear voice.

Eavesdropping on the IRS: Daddy Testifies

In September 1971, Daddy was called to Duncan’s office; Duncan “told me he had the transmitter.” He and Duncan went to Winston-Salem the same day to buy batteries for the transmitter. (We have seen that Daddy and Booner had used mics and transmitters before, so none of this activity would have been unusual.) Around 10 p.m., he and Booner went to the bank headquarters building. They took the batteries, tapes, tools, and radio transmitter to the third-floor office assigned to the IRS agents. Daddy drilled a hole in the ceiling with his pocketknife—he carried a knife wherever he went, much as I always have a mechanical pencil. In its summary of the case, the appeals court noted that the IRS had been issued keys for the office, implying that the door of the office was likely locked that night. Daddy then went into the bathroom next door to the office and climbed into the attic space above the IRS office. Duncan handed him the transmitter and “I proceeded to put it in place.”

Daddy placed a microphone about the size of a nailhead over the hole he had drilled in the ceiling. Booner wanted to test the system, so he went into the board room with an FM receiver while Daddy waited in the IRS office. “I counted from one to ten, and he hollered down the hall that it was coming in loud and clear.” He and Duncan then cleaned up the IRS office, Duncan wiped fingerprints from the inside and outside office doorknobs, and they left the bank about 11:30 that night.

Later, Daddy changed the transmitter batteries at least once. His testimony on this point was consistent with earlier testimony by Jerry Duncan, Jr. (no relation to Booner), who said that he had changed the batteries and, more important, monitored and recorded the agents’ conversations at Booner’s request. Based on the testimony at the trial, Daddy did not participate in monitoring the conversations; by the time of the trial six years later, the planting of the bug was outside the statute of limitations. (2)

Aside from Jerry Duncan and Daddy, two other bank employees were named as unindicted coconspirators, the personnel officer and a senior vice president in the consumer loan division. (3) I don’t have much information as to what these men went through, but from trial testimony we so have the perspective of the IRS agents. They used the office on the third floor of bank headquarters until January 1973, when they moved offsite, in part because they suspected they were being bugged. Agent Owen T. McCusker testified he “was conducting a criminal investigation of Duncan and Certified Check and Title Corp. at Northwestern in 1972” (4). McCusker testified that “the agents had attempted to keep the exact nature of their examination of the bank confidential and that even the bank employes interviewed did not know what the investigation was about” (5). McCusker and other agents:

“suspected that their conversations were being monitored…, according to testimony and tape recordings played yesterday at the trial of Edwin Duncan Jr…. [D]efense attorneys questioned Owen T. McCusker, a retired IRS agent, about a search of the third-floor office agents were using at the bank’s headquarters. McCusker said that agent Phillip Johnson even got up on a chair and looked into a ventilator…..

“‘In fact,’ McCusker told the jury, ‘I checked myself (for a bug). I looked at the telephone. I looked for wiring.’ But McCusker said that after finding nothing, he gave the matter little thought.” (6)

Whether Booner or his coconspirators learned anything of use to them is not clear; in the next part of the memoir, I will speculate that the IRS conversations about Certified Check and Title put the spotlight on Daddy. Since he was a key participant in CC&T’s operations, at some point they began to wonder whether he would stay mum or betray them, his friends and employer.

Eight years later, in Booner’s obituary, his daughter claimed the taping wasn’t a secret: “‘Daddy was very proud about bugging the IRS, because this was war,’ [she] said. ‘He carried the tapes open around North Wilkesboro and joked about it.’” I infer from her words that the fact of spying on the IRS was the point, more important than any information that might have been gained (7). According to the testimony of Jerry Duncan, Booner eventually lost interest in the project, though it continued for as long as the agents were located inside the bank (8). Though he was a vice president of installment loans, Jerry Duncan testified that the monitoring and recording the conversations was “his every day thing”— apparently his main activity every day (9). I should think it a demoralizing chore, especially once Booner lost interest.

Planting the bug changed Daddy’s life forever. For me, it is hard to separate the story of the bugging from the story of Daddy’s emotional deterioration between the time of the bugging and his testimony, the topic of the next part and, like at least one of my siblings, memories of these events are almost inseparable from Watergate.

In his testimony, Daddy said that he “soon suffered ‘mental anguish’ because of ‘the fact that I had violated the law,’” presumably meaning the anti-eavesdropping provisions of a 1968 federal law (the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act). “He said that ‘as soon as I realized what I had done, I started to see my doctor,’” presumably Dr. Taylor. He couldn't sleep. Soon he began taking pills prescribed by the good doctor. He stopped doing any banking business in November 1971. “Absher had been a vice president in charge of public relations. ‘After we planted the bugging device I went over on the hill and worked at manual labor. . . . I helped put in a sewer line over there . . . and I just let my public relations job go more or less to hell.’” (10)

September 1971 - August 1976

In September 1971, the month that Daddy bugged the IRS, I was preparing to leave on my mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I was working at the bank in the Time Payment Department, an area within Jerry Duncan’s scope of responsibility, though I don’t remember ever meeting him or even hearing his name. I was oblivious to Daddy’s drama. September was also the month in which the White House “Plumbers” illegally searched the office of the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg, hoping to find information to discredit him. Ellsberg was a whistleblower who had leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and other newspapers. Officially titled The History of U.S. Decision-Making in Vietnam, 1945–1968, the papers revealed the deceptions and lies behind the U.S. war effort in Viet Nam (11). It was a major story at the time; Ellsberg, one of the authors of the study, was indicted for “stealing and holding secret documents” (11), but the charges were dismissed once the burglary in September 1971 came to light. Ellsberg had discovered, as my father was soon to find out, that whistleblowers are not popular with the powers-that-be.

In November 1971, around the time Daddy stopped doing banking business, I headed to Utah for a few days at the old Mission Home in Salt Lake City then several weeks at the Language Training Mission on the campus of Brigham Young University in Provo.

Around Thanksgiving, I was struggling. At first I did not adapt to the new environment with its high expectations. I wrote a rather whining letter to Daddy, essentially asking permission to come home. (That was the gist, but I haven’t found the letter in my mission memorabilia.) Daddy answered wisely, giving me the out if I wanted it.

When I read his response, I was at first upset that he had given me the permission I requested, but from my reaction I knew I needed to stay, and so I did: he wrote wisely. As I’ve mentioned above, Daddy had stopped doing banking business; the letterhead shows that he was now working for a bank subsidiary, Northwestern Insurance Company. I may have known about this change already--I vaguely remember visiting him in an office of the insurance company on 9th Street, possibly just before I left on my mission--but I did not understand the significance until years later.

After many more years, I understand that the words in his letter applied to him as well as me. He was stepping “into an unknown realm,” not only in a new job, but in a crisis of conscience that was setting him on a collision course with Booner and his cronies; he must have had many “moments of doubt.” A sentence in the next paragraph also applied to us both, though of course I did not realize it at the time: “The only council [sic] that comes to my mind is this, ‘Walk humble before God and in pride before men,’ remembering that the darkest hour comes just before dawn.”

In January I flew to the France Paris Mission. In May 1972, while I was serving as a missionary in Poitiers, France, the Whitehouse Plumbers installed listening devices in “the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate hotel and office complex in Washington DC” (12): when it came to surveilling the opposition, Nixon was playing catchup with Booner. Much of the Watergate scandal occurred while in I was France. The news was one of many items considered distractions from our mission to teach the Gospel of Jesus Christ, so we knew little or nothing about Watergate. For the French, until perhaps the very end, it was not a big or interesting story. As we walked down the street, we would of course look curiously at the headlines, but Watergate never made it above the fold on the front page. At some point the mother of one of the missionaries in the apartment--she was not a member of the church and probably did not understand our restrictions--sent us a bundle of frontpage articles from New York papers. Watergate exploded all at once in our little space. We were stunned, but not long afterwards we refocused on our mission. That's how I remember it, at least.

Edwin Duncan, Sr., died in early October 1973. I returned from France in November, worked at the bank for a couple of months, returned to BYU as a sophomore in January 1974, and was married in August that year, on the day that Nixon flew away from the White House into political exile. I had worked at the bank that summer, but it was the last time. So far as I remember, I still knew nothing about the bugging of the IRS in 1971-1972.

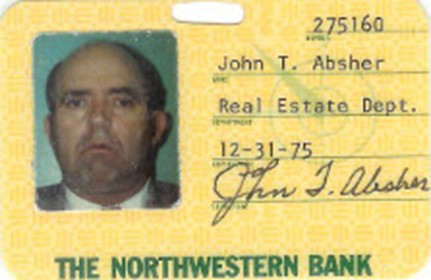

I graduated from BYU in August 1976 and with my then wife moved to Durham, North Carolina, where I enrolled in graduate school at Duke University. I think it was in this period that Daddy occasionally shared tidbits about questionable practices at the bank, and on my trips home I could see that he was deteriorating mentally and emotionally. But I was too wrapped up in my own life and concerns to ask questions or foresee the coming disaster.

After many more years, I understand that the words in his letter applied to him as well as me. He was stepping “into an unknown realm,” not only in a new job, but in a crisis of conscience that was setting him on a collision course with Booner and his cronies; he must have had many “moments of doubt.” A sentence in the next paragraph also applied to us both, though of course I did not realize it at the time: “The only council [sic] that comes to my mind is this, ‘Walk humble before God and in pride before men,’ remembering that the darkest hour comes just before dawn.”

In January I flew to the France Paris Mission. In May 1972, while I was serving as a missionary in Poitiers, France, the Whitehouse Plumbers installed listening devices in “the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate hotel and office complex in Washington DC” (12): when it came to surveilling the opposition, Nixon was playing catchup with Booner. Much of the Watergate scandal occurred while in I was France. The news was one of many items considered distractions from our mission to teach the Gospel of Jesus Christ, so we knew little or nothing about Watergate. For the French, until perhaps the very end, it was not a big or interesting story. As we walked down the street, we would of course look curiously at the headlines, but Watergate never made it above the fold on the front page. At some point the mother of one of the missionaries in the apartment--she was not a member of the church and probably did not understand our restrictions--sent us a bundle of frontpage articles from New York papers. Watergate exploded all at once in our little space. We were stunned, but not long afterwards we refocused on our mission. That's how I remember it, at least.

Edwin Duncan, Sr., died in early October 1973. I returned from France in November, worked at the bank for a couple of months, returned to BYU as a sophomore in January 1974, and was married in August that year, on the day that Nixon flew away from the White House into political exile. I had worked at the bank that summer, but it was the last time. So far as I remember, I still knew nothing about the bugging of the IRS in 1971-1972.

I graduated from BYU in August 1976 and with my then wife moved to Durham, North Carolina, where I enrolled in graduate school at Duke University. I think it was in this period that Daddy occasionally shared tidbits about questionable practices at the bank, and on my trips home I could see that he was deteriorating mentally and emotionally. But I was too wrapped up in my own life and concerns to ask questions or foresee the coming disaster.

Daddy’s deterioration is evident in his bank id card from December 1975

The following poem explores the situation through invented incidents and words. I wrote it before I had my current grasp of chronology and bank culture, so in many respects it’s not an accurate account. He did not listen in on the conversations of the IRS agents, and there’s no evidence he listened to the tapes, but I suspect he may have done so, especially at the beginning. The poem conflates that bugging of the IRS and the later bugging of the FBI. The character of the talky bugger is an invention, a type, and is not intended as the depiction of any actual person. Still, I hope the poem captures some of the emotional and moral truths of his story. In the poem, Booner becomes Junior; I didn’t know this at the time, but Booner comes from how the very young Edwin Duncan, Jr., pronounced his name.

The Green Noise of the World

i.

I imagined old man Duncan could snap

the thumb of his good hand across the head

on a double sawbuck and tell who had held it--

grease monkey, reverend, beautician—as if

the paper had been inked with their souls.

When he was dying, he pulled Junior’s

ear to his lips, Only you under the stars

and under the sun can keep the thing going.

(Junior had to stoop to catch the words.

More tears in the old man’s eyes than his.)

The IRS is on to you-know-what:

their auditors have bugged our damned comptroller--

they’re grabbing for our balls. You have it all.

To keep it, little man, you’ll have to dance.

ii.

Junior found people worth knowing—a man

who showed him how to squirrel away his cash

into a nut so hard no auditor

could crack it; another, who could hide

a transmitter in the olive in a martini.

After a fifth of Junior’s shine, the tongue

of the bugger flapped: When the mark speaks,

the whole room resonates. All you have to do

is capture and amplify. When you’ve played

hours of scratchy tapes—through the white noise

of transistor hiss, then the softer static

of white filtered to pink in flickering circuits--

you’ll know the goddamn joy of catching

the little words needed to goddamn ruin a man.

iii.

Junior picked me out for something bigger.

We go back a ways, I knew your daddy,

you worked for mine. Are you ready

to quit dicking with your career? Junior

gave me his Italian shotgun, an over

and under engraved with two gold pheasants.

He gave me a Plymouth. Don’t sweat the expense,

you’ll need some elbow room to maneuver,

and cash is a cold-cock tool that spreads

the world as broad as a man’s needs.

Into my jacket pocket he slipped some money.

His right arm went across my shoulders,

he held my right hand in his left and whispered

in my ear drops of poison as thick as honey.

iv.

I’ve lent money to Landreths, Clonches, Woodards,

their skin white as talcum, to black men liable

to come in, named the same, and make their answers

yes, sir, no, sir, like it says in the Bible:

when cash was in their pocket, the dark world

shone wet and lucent, a glassine envelope;

when money was in both pockets, the men swaggered

and whistled down 10th Street, inflated with hope,

the payback lurking where they couldn’t see it.

It was fine to be vice president of this,

to see the money spread out, steaming manure

on poor land, to see it catch on fire and heat

the county, like Nebuchadnezzar’s furnace.

In it I stood, stoking it bluer, bluer.

v.

Yellow ears were bursting from the shuck,

the morning fog was glowing in the sun,

when Junior found me, See these two transmitters?

He held his left hand out. I have just one

little job for you, then we’ll be partners,

stepping shoulder to shoulder, cheek to cheek.

I’ll keep you closer than my finger bone.

I drove through the roaring boom of traffic

to buy the batteries where no one knew me

by face or name. In a ceiling tile

of the office reserved for IRS auditors

I used my pocketknife to cut a pinhole,

then climbed on the sink next door to shimmy

into the crawl space to plant the little bastard.

vi.

Later I drove to the river, played the last tape,

and listened: the shuffling of papers as the agents

traced and vouched cash. The clicking ten-keys.

A cassette tinkling country, Can’t sleep a wink,

that is true, then an old movie tune, Let's

face the music. I pondered the muteness

of the stars, the silent spinning of the earth--

the vast listening of God who cannot stop

his ears against our racket. As I woke

the sky was whitening east to west and flushing

pink at the margin. I wondered (why hadn’t

I thought of it before?) what’s Junior’s done

with the second bug? I reached under the dash,

under the seat. I pulled off the heel of my shoe.

vii.

This morning, I heard a buzzing, like flies

around a carcass, whispers like corduroy on

corduroy, sifted meal sliding down itself.

Then a voice came from the dirt, Get up, John,

the birds wait. Even the children go

unafraid. I rose to the commotion

in the trees, the house full of strange

perfumes invited me to open the white

doors, to look at sleepers helpless in night

clothes, while their cold paws tunneled the stale

air of dreams. The voice commanded, Go, dig

with the moles, find the wiring by which

a man can tap the green noise of the world.

Now my head crackles like a radio.

Anderbo, Fall 2009, slightly revised.

Posted 12 April 2024, updated 13, 17 April 2024.

Please send comments, critiques, and questions to [email protected].

NOTES

Note 1: Screenplay of The Conversation, script slug (https://www.scriptslug.com/script/the-conversation-1974). The headline is from Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Sep 1977, 1.

Note 2: “Witness Says He Helped Duncan Install Transmitter,” Sentinel, 27 Sep 1977, 1-2; David Bailey, “Edwin Duncan Trial: Witness ‘Anguished’ by Bugging (changed in a later edition to “Witness Says Bugging Bugged Him”), Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Sep 77, 1-2; United States v. Edwin Duncan, Jr., 598 F.2d 839 (4th Cir. 1979) https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/366306/united-states-v-edwin-duncan-jr/; “Witness Says He Helped Duncan Install Transmitter,” Sentinel, 27 Sep 1977, 1-2.

Note 2: “Witness Says He Helped Duncan Install Transmitter,” Sentinel, 27 Sep 1977, 1-2.

Note 3: David Bailey, “Duncan Faces 3 Charges in Trial Here This Week,” Winston-Salem Journal, 25 Sep 1977, B1, B3.

Note 4: David Bailey, “Tape Is Played for Jury in Duncan Case,” Winston-Salem Journal, 29 Sep 1977, 1, 2

Note 5: Mark Wright, “Prosecution Plays 3 Tapes at Duncan’s Bugging Trial,” Sentinel, 28 Sep 1977, 1, 2.

Note 6: David Bailey, “Tapes Indicate Bugging Suspected,” Winston-Salem Journal, 30 Sep 1977, 1, 2.

Note 7: John Byrd, “Edwin Duncan, Former Bank Chairman, Dies,” Winston-Salem Journal, 7 Mar 1985, 4. During the trial in 1977, George Collins (president of the bank) testified he told the FBI that the bugging "'was no secret. . . that a large number of people knew about it'" (Mark Wright, “Prosecution Calls FBI Man in Duncan Bugging Trial,” Sentinel, 28 Sep 1977, City ed., 1, 2).

Note 8: “Duncan Gave Taping Order, Witness Says,” Winston-Salem Journal, 27 Sep 1977, 1-2. The defense argued that Booner’s interest in the bugging lasted only during the period outside the statute of limitations—impossible to prove and irrelevant, since the bugging he ordered continued well beyond that period.

Note 9: “Former Officials of Bank Testify,” Journal-Patriot, 29 Sep 1977, A1, A12.

Note 10: David Bailey, “Edwin Duncan Trial: Witness ‘Anguished’ by Bugging,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Sep 1977, 1-2; “Witness Says He Helped Duncan Install Transmitter,” Sentinel, 27 Sep 1977, 1-2.

Note 11: Wikipedia has a useful summary (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pentagon_Papers).

Note 12: https://web.archive.org/web/20120505222315/http://watergate.info:80/chronology/1972.shtml