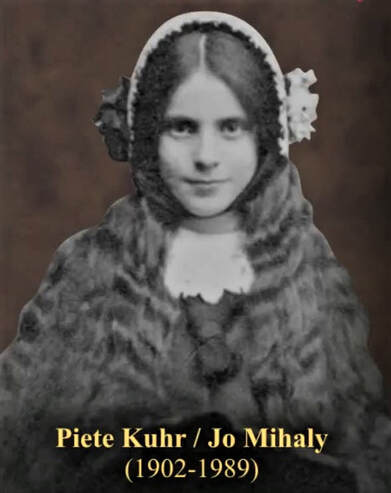

An extraordinary diary to emerge from the war was written by Piete Kuhr. Aa teenager during the war, she went on, as Jo Mihaly, to become an anti-war Expressionist dancer in Berlin in the 20’s and 30’s, to write novels, and in 1933 to flee Germany with her Jewish husband. The following passage, from 30 August 1918, juxtaposes her grief at losing a friend, Lieutenant Waldecker, with the funeral of the fictitious Lieutenant von Yellenic elaborately staged by Piete and her friend Gretel. Like Piete herself, one hardly knows whether to laugh or cry: “No one else was in the house. I covered the camp bed in [my brother’s] room with a cloth and with old sheets and pillows. I made up a life-size dummy…, covered it with a black coach-rug to make it look as if there was a body underneath. Then I put Uncle Bruno's old army boots under the rug. I put a dented steel helmet where Lieutenant Yellenic's head was. I placed my uncle's old cavalry sword and a little bunch of dried lilac … where the hands should have been. I made two Iron Crosses, first and second class, out of cardboard and a paper 'Order of Merit' which Lieutenant von Yellenic had been awarded after his 80th 'kill' in his fighter-plane 'Flea'. I laid out these three medals on Grandma's blue velvet pincushion, then I drew the curtains and lit two candles at the head of the corpse. They were only two little stumps really, but as they were stuck in Grandma's tall brass candlesticks they looked a bit like big funeral candles. After all this I shut the door.

Meanwhile, Gretel had dressed up as the mourning 'Nurse Martha'. She wore Grandma's black dress,… a thin black veil and ... a white handkerchief.… I sat down at the piano and played Chopin's 'Funeral March', then I beat a slow-march rhythm on a saucepan covered with a cloth. It sounded just like a drum roll at a military funeral. The procession then made its way from the bedroom through the dining and drawing rooms. I rushed back to the piano to play 'Jesus, my protector and saviour, lives', and Gretel instantly started to cry—they were real tears. Now came the high point: I opened the double doors. Gretel whispered 'Oh God!' when she saw Lieutenant von Yellenic's corpse in full war regalia in the candlelight, and I must say that it really looked as if there was a dead officer lying there. Nurse Martha sobbed as if her heart was about to break, for she was of course secretly in love with Lieutenant von Yellenic. I didn't know whether to roar with laughter or cry. I was near to both, but then it suddenly struck me that the whole affair resembled Lieutenant Waldecker's funeral procession. I made a speech about Flight Lieutenant von Yellenic, honouring his 80 'kills' and burst three paper bags which I had blown up. And so ended the game of Nurse Martha and [Lieutenant] von Yellenic.” [Source: Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis, ed. A War in Words: The First World War in Diaries and Letters]. ***** Strange Meeting by Wilfred Owen It seemed that out of battle I escaped Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped Through granites which titanic wars had groined. Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned, Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred. Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared With piteous recognition in fixed eyes, Lifting distressful hands, as if to bless. And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,-- By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell. With a thousand fears that vision's face was grained; Yet no blood reached there from the upper ground, And no guns thumped, or down the flues made moan. “Strange friend,” I said, “here is no cause to mourn.” “None,” said that other, “save the undone years, The hopelessness. Whatever hope is yours, Was my life also; I went hunting wild After the wildest beauty in the world, Which lies not calm in eyes, or braided hair, But mocks the steady running of the hour, And if it grieves, grieves richlier than here. For by my glee might many men have laughed, And of my weeping something had been left, Which must die now. I mean the truth untold, The pity of war, the pity war distilled. Now men will go content with what we spoiled. Or, discontent, boil bloody, and be spilled. They will be swift with swiftness of the tigress. None will break ranks, though nations trek from progress. Courage was mine, and I had mystery; Wisdom was mine, and I had mastery: To miss the march of this retreating world Into vain citadels that are not walled. Then, when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels, I would go up and wash them from sweet wells, Even with truths that lie too deep for taint. I would have poured my spirit without stint But not through wounds; not on the cess of war. Foreheads of men have bled where no wounds were. “I am the enemy you killed, my friend. I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed. I parried; but my hands were loath and cold. Let us sleep now. . . .” [Source: Dominic Hibberd and John Onions, The Winter of the World] Editors’ note: “Written March–May 1918…. Owen’s first, worst memory of the front was of a captured dugout where he and his men had almost been buried alive, a horror that must often have recurred in his shellshock nightmares. As Edmund Blunden noted, the poem is ‘a dream only a stage further on than the actuality of the crowded dugouts’. But it is also a very literary vision, Owen’s farewell to poetry, with echoes of Homer, the Bible, Dante, Spenser, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson and many others. Acutely aware of the crisis at the front, he foresees his own likely death, expects his poetry to achieve nothing and – unlike most of the war’s poets – faces up to the full implications of killing.” ***** Although written in early 1919, this poem by a survivor of the war, Siegfried Sassoon, captures the joy of being liberated from the war. Everyone Sang Everyone suddenly burst out singing; And I was filled with such delight As prisoned birds must find in freedom, Winging wildly across the white Orchards and dark-green fields; on – on – and out of sight. Everyone’s voice was suddenly lifted; And beauty came like the setting sun: My heart was shaken with tears; and horror Drifted away ... O, but Everyone Was a bird; and the song was wordless; the singing will never be done. [Source: The Winter of the World]

0 Comments

Edward Thomas Photograph: E.O. Hoppe/Corbis. From: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/may/31/edward-thomas-adlestrop-to-arras-review-jean-moorcroft-wilson “[K]illed at Arras on that first day of the battle [April 9] was the British poet Edward Thomas, who so loved the English countryside:

A Private This ploughman dead in battle slept out of doors Many a frozen night, and merrily Answered staid drinkers, good bedmen, and all bores: "At Mrs Greenland's Hawthorn Bush," said he, "I slept." None knew which bush. Above the town, Beyond `The Drover', a hundred spot the down In Wiltshire. And where now at last he sleeps More sound in France - that, too, he secret keeps. [Source: Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History] ***** Douglas Lyall Grant, a British POW in a German prison camp, on 28th January 1917 – “Renewed joy in the morning when it was discovered that two Russians had escaped last night. We wish them all the best of luck and a rapid journey over the frontier. The method of their escape was particularly cunning. Each day Russian orderlies wheel out barrels of refuse to a ground nearby where the pigs are kept. Today two of these barrels had refuse on the top but Russians underneath.” ***** “The Italian soldiers had not illusions about a swift breakthrough [at the 10th Battle of the Isonzo, beginning 10 May 1917]. Among their many jingles was the verse: Il General Cadorna Ha scritta alla Regina 'Se vuoi veder Trieste, Compra una cartolina.'" Gilbert translates: "General Cadorna / Has written to the Queen, / 'If you want to see Trieste, / Buy a picture postcard." [Source: Gilbert, The First World War] ***** Elias Canetti in the first volume of his memoirs: “I was twelve when I got passionately interested in the Greek wars of liberation, and that same year, 1917, was the year of the Russian Revolution. Even before his journey in the sealed freight car, people were speaking about Lenin living in Zurich [where Canetti lived with his mother]. Mother, who was filled with an insatiable hatred of the war, followed every event that might terminate it. She had no political ties, but Zurich had become a center for war opponents of the most diverse countries and tendencies. Once, when we were passing a coffeehouse, she pointed at the enormous skull of a man sitting near the window, a huge pile of newspapers lay next to him; he had seized one paper and held it close to his eyes. Suddenly, he threw back his head, turned to a man sitting at his side and fiercely spoke away at him. Mother said: ‘Take a good look at him. That’s Lenin. You’ll be hearing about him.’ We had halted, she was slightly embarrassed about standing like that and staring…, but his sudden movement had struck into her, the energy of his jolting turn towards the other man had transmitted itself to her … I was … astonished at Mother’s immobility. She said: ‘Come on, we can’t just stand here,’ and she pulled me along….. She never the called the war anything but ‘the killing.’ Since our arrival in Zurich, she had talked about it very openly to me; in Vienna, she had held back to prevent my having any conflicts at school. ‘You will never kill a person who hasn’t done anything to you,’ she said beseechingly; and proud as she was of having three sons, I could sense how worried she was that we too might become such ‘killers’ some day. Her hatred of war had something elemental to it: Once, when telling me the story of Faust, which she didn’t want me to read as yet, she disapproved of his pact with the devil. There was only one justification for such a pact: to put an end to the war. You could even ally yourself with the devil for that, but not for anything else.”—Elias Canetti, The Tongue Set Free ***** In Memoriam Private D. Sutherland killed in action in the German trench, May, 16, 1916, and the others who died [published in 1917] by E.A. Mackintosh So you were David’s father, And he was your only son, And the new-cut peats are rotting And the work is left undone, Because of an old man weeping, Just an old man in pain, For David, his son David, That will not come again. Oh, the letters he wrote you, And I can see them still, Not a word of the fighting, But just the sheep on the hill And how you should get the crops in Ere the year get stormier, And the Bosches have got his body, And I was his officer. You were only David’s father, But I had fifty sons When we went up in the evening Under the arch of the guns, And we came back at twilight-- O God! I heard them call To me for help and pity That could not help at all. Oh, never will I forget you, My men that trusted me, More my sons than your fathers’, For they could only see The little helpless babies And the young men in their pride. They could not see you dying, And hold you while you died. Happy and young and gallant, They saw their first-born go, But not the strong limbs broken And the beautiful men brought low, The piteous writhing bodies, They screamed “Don’t leave me, sir”, For they were only your fathers But I was your officer. [Source: Winter of the World] Editor’s note: “Young officer-poets who wrote about their men often used the language of love poetry…. Mackintosh had carried the badly wounded Sutherland out of a German trench, pursued by the enemy, but the man had died before he could be got to safety.” Here's my own take on that bloody year. Days of 1917 On the eighth day God looked and the world was mad. He sent forth a pouter pigeon, saying, Alight in a poor out of the way place, maybe southern Appalachia, then fly around the world, flitting up and down, and tell me if any cling to tatterdemalion faith. Shall I release the waters of another flood? Perched above brick-red plots she sees men and women scratch the dirt like hungry biddies, sees drivers and wagons hauling chestnut bark lined up at a tannery, a line of barefoot women selling them apple brandy-- they call it corpse-reviver, gall-breaker, gum-tickler, milk of the wild cow, pain drowner: Pigeon calls it wife-beater and bust-head. She takes flight, the world below snorts and bites its stall: fire coals belch from sawmill boilers, the bristling Atlantic scrapes its tusks against Hatteras. She flies eastward, over seas spattered with white caps and periscopes and bodies of sailors who once swaggered and cussed like gods. She reaches a guarded mount, turns inland, and skims over Polygon Wood, racing ahead of a creeping barrage inundating no-man’s land with fire. She hovers over Tommies engulfed by mustard gas, over Jerries out of sight who suffocate in mud, though once they could swim the length of a pond on one deep breath. Here and there a comrade dies to rescue one he loves, a padre breathes life into one who is losing hope. The pigeon looks up to heaven. They’re drowning themselves ready enough. You can hold off.  Isaac Rosenberg Source: https://mypoeticside.com/poets/isaac-rosenberg-poems January 1916

“[T]he last British troops left Cape Helles on the Gallipoli Peninsula. … Thirty-three Commonwealth war cemeteries on the peninsula contain the graves of those whose bodies were found. On the grave of Gunner J.W. Twamley his next of kin caused the lines to be inscribed: Only a boy but a British boy, The son of a thousand years. A bereaved Australian sent the following lines: Brother Bill a sniping fell: We love him still, We always will. From parents whose grief could not find comfort in religion came the question: What harm did he do Thee, O Lord?” [Source: Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History] ***** February Afternoon by Edward Thomas Men heard this roar of parleying starlings, saw, A thousand years ago even as now, Black rooks with white gulls following the plough So that the first are last until a caw Commands that last are first again, – a law Which was of old when one, like me, dreamed how A thousand years might dust lie on his brow Yet thus would birds do between hedge and shaw. Time swims before me, making as a day A thousand years, while the broad ploughland oak Roars mill-like and men strike and bear the stroke Of war as ever, audacious or resigned, And God still sits aloft in the array That we have wrought him, stone-deaf and stone-blind. [Source: Dominic Hibberd and John Onions, The Winter of the World] ***** Spreading Manure by Rose Macaulay There are forty steaming heaps in the one tree field, Lying in four rows of ten, They must be all spread out ere the earth will yield As it should (And it won’t, even then). Drive the great fork in, fling it out wide; Jerk it with a shoulder throw, The stuff must lie even, two feet on each side. Not in patches, but level…so! When the heap is thrown you must go all round And flatten it out with the spade, It must lie quite close and trim till the ground Is like bread spread with marmalade. The north-east wind stabs and cuts our breaths, The soaked clay numbs our feet, We are palsied like people gripped by death In the beating of the frozen sleet. I think no soldier is so cold as we, Sitting in the frozen mud. I wish I was out there, for it might be A shell would burst to heat my blood. I wish I was out there, for I should creep In my dug-out and hide my head, I should feel no cold when they lay me deep To sleep in a six-foot bed. I wish I was out there, and off the open land: A deep trench I could just endure. But things being other, I needs must stand Frozen, and spread wet manure. [Source: The Winter of the World] Editors’ note: In England, “many women volunteered to replace men as land workers; like soldiers in the trenches, they suffered in the exceptionally harsh winter of 1916–17.” The winter was harsh throughout Europe and was particularly hard on soldiers in wet trenches, civilians in blockaded economies like Germany’s, and on prisoners of war, especially those who, like Russian soldiers, were not assisted by their governments. Alexei Zyikov, a Russian soldier from Moscow, was captured in 1915 and in 1916 was being held in Marienburg POW camp in north-eastern Germany. In his first diary entry he wrote: “Hunger does not give you a moment's peace and you are always dreaming of bread: good Russian bread! There is consternation in my soul when I watch people hurling themselves after a piece of bread and a spoonful of soup.… We work from dawn till dusk, sweat mingling with blood; we curse the blows of the rifle butts; I find myself thinking about ending it all, such are the torments of my life in captivity! [He had been held for 11 months.] On Sunday we did no work but stood around outside our huts under the gaze of the Germans with their wives and children, full of curiosity and hate watching us from their windows and from the street. And, it was wonderful, they could see that we were people too and they began to come a little closer. But then some of the little German children began hurling stones at us.… [N]othing surprises me here - like today, I saw a soldier rummaging in a rubbish pit, picking out potato and swede peelings and eating them slowly to make them last. The hunger is dreadful: you feel it constantly, day and night. You have to forget who you once were and what you've become.” Zyikov's entries stopped in 1917. His fate is unknown. His diary was discovered in WW2 by Russian soldiers who had invaded the Third Reich. [Source: Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis, ed. A War in Words: The First World War in Diaries and Letters] ***** Returning, We Hear the Larks by Isaac Rosenberg Sombre the night is: And, though we have our lives, we know What sinister threat lurks there. Dragging these anguished limbs, we only know This poison-blasted track opens on our camp-- On a little safe sleep. But hark! Joy—joy—strange joy. Lo! Heights of night ringing with unseen larks: Music showering on our upturned listening faces. Death could drop from the dark As easily as song-- But song only dropped, Like a blind man's dreams on the sand By dangerous tides; Like a girl's dark hair, for she dreams no ruin lies there, Or her kisses where a serpent hides. [Source: The Winter of the World] ***** In the summer of 1916, Rosenberg, then serving in France, looked back on the war’s beginning: August 1914 What in our lives is burnt In the fire of this? The heart’s dear granary? The much we shall miss? Three lives hath one life – Iron, honey, gold. The gold, the honey gone – Left is the hard and cold. Iron are our lives Molten right through our youth. A burnt space through ripe fields A fair mouth’s broken tooth. [Source: The Winter of the World] Edited 12 November 2023 The entries below were written by a British civilian, a Russian soldier on the Eastern Front, a thirteen-year-old Prussian schoolgirl, a widow in a besieged city in Galicia, British soldiers in Flanders and the Dardanelles, a Turkish officer in the Dardanelles, an unknown Austrian officer fighting the Italians in the Alps, Rudyard Kipling (whose son John had been killed in unknown circumstances in France), and Thomas Hardy.

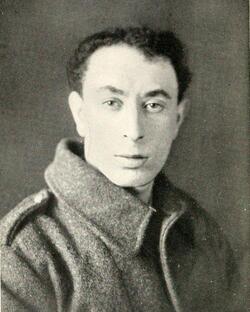

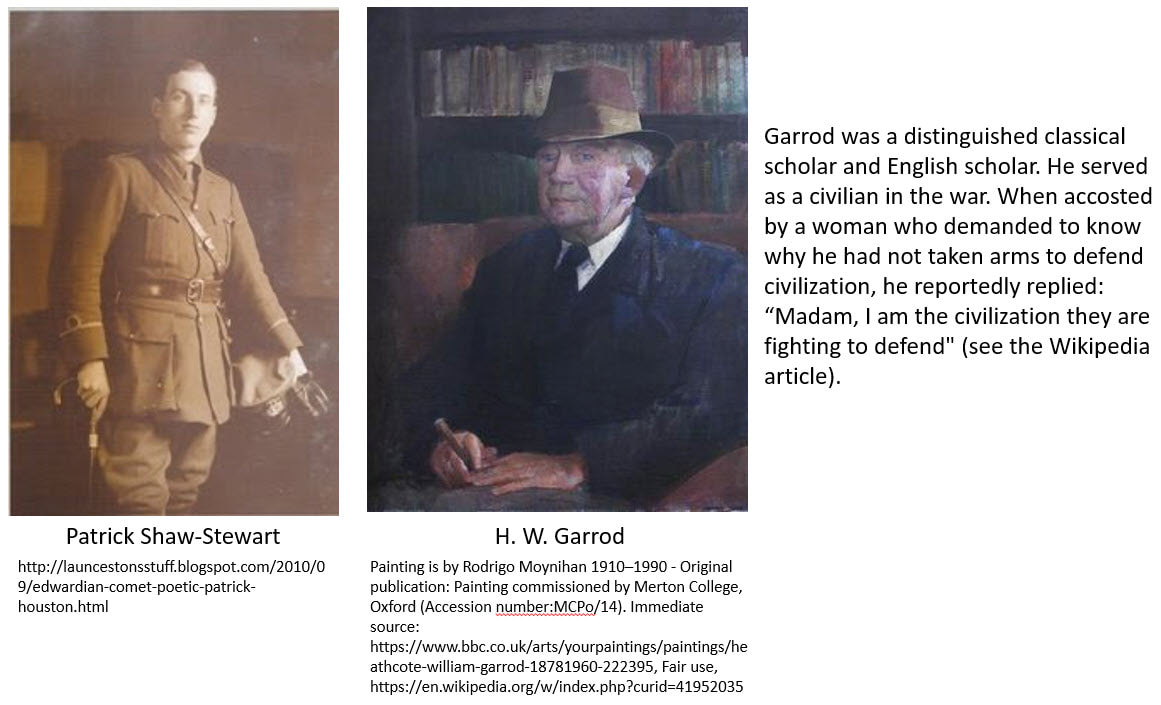

Epitaph: Neuve Chapelle by H.W. Garrod Tell them at home, there's nothing here to hide: We took our orders, asked no questions, died. [Source: Dominic Hibberd and John Onions, The Winter of the World] ***** In his journal entry for 27 January, Russian soldier Vasily Mishnin describes being under artillery fire. The men break and run. Mishnin and a comrade hide in a hut: "We press ourselves against a wall, sit down and wipe our tears. Our eyes are full of tears, we wipe them away, but they just keep coming because the shells are full of gas. We are terrified. [We] lie face down and we just want to dig ourselves into the earth. Under our breath we pray to our Lord God to save us from this, just for this one day. Dear Nyurochka [his wife], pray for me in this terrible hour, and forgive me if I am guilty of anything. Dear God, are you really sitting up there in heaven without hearing or saying anything?" [Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis, ed. A War in Words: The First World War in Diaries and Letters] ***** On March 11, the Prussian schoolgirl, Piete Kuhr, wrote in her journal: “Another collection has been announced at school, for copper, again, but also for tin, lead, zinc, brass and old iron to make gun-barrels, field guns, cartridge cases and so forth. There is a keen competition between the classes. Our class, the fourth, has so far collected the most. I turned the whole house over from top to bottom. Grandma cried, 'the wench will bankrupt me! Why don't you give them your lead soldiers instead of cleaning me out!' So my little army had to meet their deaths.” ***** Helena Seifertóv Jabłońska was trapped by the Russian army in a besieged fortress city in Galicia, a province of Austria-Hungary. She had refused to leave because she did not want to abandon her husband’s grave. On March 15, she wrote: ”The Russians have burned nearly all the surrounding villages. In one village the inhabitants locked themselves into their huts to keep out the Russians. The Russians boarded up the doors from the outside and set fire to the huts. There is no longer any doubt that we will have to surrender. Betrayal and hunger have exhausted us. .... [The soldiers] are mere shadows, not people, they are skeletons, not men. The peasants have had everything taken from them, so as not to leave anything for the Russians. This was done ruthlessly, without any compassion. An act unworthy of the civilised Catholic nation that we are. It was cruel to give such an order, but those executing it were crueller still. How generous of them to leave the peasants their lives!” ***** Sidney Appleyard remembered a soldiers’ marching song from May 1915 in Flanders written by the “platoon poet, Bill Bright”: I’m a bomber, I'm a bomber Wearing a grenade, The Army's got me where it wants, I'm very much afraid. When decent jobs are going I never get a chance, Which shows what bloody fools we were To volunteer for France." [Source: Andrew Roberts, Elegy: The First Day on the Somme] ***** In the Gallipoli campaign, a British officer at Cape Helles wrote about returning to the front after a brief leave: 'I saw a man this morning' by Patrick Shaw-Stewart I saw a man this morning Who did not wish to die: I ask, and cannot answer, If otherwise wish I. Fair broke the day this morning Against the Dardanelles; The breeze blew soft, the morn's cheeks Were cold as cold sea-shells. But other shells are waiting Across the Aegean Sea, Shrapnel and high explosive, Shells and hells for me. O hell of ships and cities, Hell of men like me, Fatal second Helen, Why must I follow thee? Achilles came to Troyland And I to Chersonese: He turned from wrath to battle, And I from three days' peace. Was it so hard, Achilles, So very hard to die? Thou knewest, and I know not-- So much the happier I. I will go back this morning From Imbros over the sea; Stand in the trench, Achilles, Flame-capped, and shout for me. Two years later, Shaw-Stewart was killed on the Western Front. This poem—his only surviving complete poem—was found after his death in his copy of Housman’s A Shopshire Lad. [Hibberd and Onions, The Winter of the World: Poems of the Great War] ***** On 22 November, Mehmed Fasih, a Turkish officer fighting opposite Shaw-Stewart, wrote in his diary: “05.00 hrs. Daydream about a happy family and nice kids. Will I live to see the day when I have some? I know I should be infinitely grateful for what I do have, but why have I not, to this day, been able to find real happiness, the kind that sets the heart free and brings comfort to the soul? Dear God! Will you ever grant such things to be my lot in life?” [A War in Words] ***** From the diary of an unknown Austrian officer, 18th July 1915, fighting the Italian army in the Alps: “In the night the artillery fire became insanely heavy. This is the end, I thought, and prepared to die like a proper Christian. But I am still so young! To die without a confession, without the words of comfort and faith of our holy religion! Oh Italy, may God punish your king and your treacherous people.” [A War in Words] ***** The Children By Rudyard Kipling These were our children who died for our lands: they were dear in our sight. We have only the memory left of their home-treasured sayings and laughter. The price of our loss shall be paid to our hands, not another’s hereafter. Neither the Alien nor Priest shall decide on it. That is our right But who shall return us the children? At the hour the Barbarian chose to disclose his pretences, And raged against Man, they engaged, on the breasts that they bared for us, The first felon-stroke of the sword he had long-time prepared for us – Their bodies were all our defence while we wrought our defences. They bought us anew with their blood, forbearing to blame us, Those hours which we had not made good when the judgment o’ercame us. They believed us and perished for it. Our statecraft, our learning Delivered them bound to the Pit and alive to the burning Whither they mirthfully hastened as jostling for honour – Not since her birth has our Earth seen such worth loosed upon her. Nor was their agony brief, or once only imposed on them. The wounded, the war-spent, the sick received no exemption: Being cured they returned and endured and achieved our redemption, Hopeless themselves of relief, till Death, marvelling, closed on them. That flesh we had nursed from the first in all cleanness was given To corruption unveiled and assailed by the malice of Heaven – By the heart-shaking jests of Decay where it lolled on the wires – To be blanched or gay-painted by fumes – to be cindered by fires – To be senselessly tossed and retossed in stale mutilation From crater to crater. For this we shall take expiation. But who shall return us our children? [The Winter of the World] ***** This post is already too long, but I cannot leave without this poem from December: The Oxen by Thomas Hardy Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock. “Now they are all on their knees,” An elder said as we sat in a flock By the embers in hearthside ease. We pictured the meek mild creatures where They dwelt in their strawy pen, Nor did it occur to one of us there To doubt they were kneeling then. So fair a fancy few would weave In these years! Yet, I feel, If someone said on Christmas Eve, “Come; see the oxen kneel, “In the lonely barton by yonder comb Our childhood used to know,” I should go with him in the gloom, Hoping it might be so. Edited 11 November 2023  Anna Akhmatova For five days beginning today, I am going to post a poem or two from the Great War, beginning with poems written in 1914, and ending in poems written in 1918. I’ll also add some other items, including contemporary journal entries.

For the most part, I’ll be posting items I copied into my journal in 2017 when I was preparing to teach the literature of the First World War at Southern Virginia University. The class grows in importance for me as it recedes into the past, perhaps because the preparation for the class led me to read a large body of literature in a short time, reminiscent in a way of grad school but much more rewarding. A year ago I wrote that the conditions of another world war appear to be forming. The events of the last year, and especially the last month, have only moved us closer to it. May Providence and chance, wisdom and stupidity combine to prevent it. Today’s first poem is by Akhmatova. In Memoriam, July 19, 1914 by Anna Akhmatova We aged a hundred years and this descended In just one hour, as at a stroke. The summer had been brief and now was ended; The body of the ploughed plains lay in smoke. The hushed road burst in colors then, a soaring Lament rose, ringing silver like a bell. And so I covered up my face, imploring God to destroy me before battle fell. And from my memory the shadows vanished Of songs and passions—burdens I'd not need. The Almighty bade it be—with all else banished-- A book of portents terrible to read. Translation by Stephen Edgar. Source: http://www.worldwarone.it/2016/06/the-poets-and-world-war-in-memoriam.html. Diaries. These entries show two children and an adult philosopher dealing with the outbreak of war. The 12-year-old Prussian schoolgirl Piete Kuhr began a diary and wrote (1 Aug 1914): "At school the teachers say it is our patriotic duty to stop using foreign words. I didn't know what that meant at first, but now I see it—you must no longer say 'Adieu' because that is French. I must now call Mama 'Mutter'. At school they talk of nothing but the war now.” [Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis, ed. A War in Words: The First World War in Diaries and Letters] On 4 August, Piete wrote: “The 149th Infantry Regiment is stationed in our town, Schneidemühl. They are going to be sent to the Western Front. This evening we heard the far off sound of the drums, bass drums and kettledrums. The music kept getting louder and clearer. We couldn't bear to stay in our room and ran out into the street.… Our regiment was marching down the street to the station. The soldiers wore new grey uniforms and black spiked helmets. They were looking serious. I had expected them to be laughing and rejoicing. A trumpet call rang out. A soldier as big as a tree came past me. I stretched out my hand over the fence and muttered 'Farewell!' He smiled at me and shook my hand. I gazed after him. Gradually the train began to move. It wouldn't have taken much for me to burst out crying. I went home by a roundabout way. I held my hand out in front of me, the one that the soldier had squeezed. As I went up our poorly lit steps, I stared at the palm of my hand. Then I quickly kissed it.” Yves Congar, a French schoolboy in Sedan in eastern France, also began an illustrated diary about this time. This mixture of quotation and summary is from his entry for 25 August: "We are just getting up when mother comes up to me and says, ‘….Put your soldiers away, the Germans are coming.' I go outside after putting them away and I hear shooting and I see a plane in the sky. As soon as I am back inside, my big brothers come through the door. 'They're coming! They're coming! They're right behind us!' I go and look out the dining-room widow." Yves watches through the wind as "the shooting starts." The German soldiers charge; he hears two massive thuds "as two horses fall dead in front of the window. Bullets whizz by in both directions." They can hear artillery, machine guns, and rifles; they hear the "Germans hitting Mr Benoit's door with their rifle butts, looking for French troops. Just to be safe they shoot Mr Benoit's dog, so that its barking won't interfere with their patrols." In the evening, they hear bridges being blown up. "The Germans, fiends, thieves, murderers and arsonists ... set fire to everything: to our church in Givonne; to the chapel in Fond de Givonne Glaire; to Donchery, where they use incendiary rockets....." Next day, the Germans demand "a quarter of a million francs' worth of gold." (Source: A War in Words) Sedan was occupied for almost the entire war. Ludwig Wittgenstein. Tuesday 18th August, 1914: In his private diary, LW notes that last night he was awakened suddenly at 1 a.m., when his lieutenant asked him to man the searchlight immediately. LW ran to do so, almost naked, in icy air and rain. ‘I was sure I would die’. He turned on the searchlight, then went back to get dressed. ‘I felt the horrors of war’, he notes. Writing this diary entry later, in the evening, he feels he has overcome the shock again, and resolves to hold on to life ‘with all my strength.’ (http://www.wittgensteinchronology.com/7.html) Wednesday 19th August, 1914: Around this time, LW buys a copy of Tolstoy’s book The Gospel in Brief from an impoverished bookshop in Tarnów, Galicia, which has only this single book remaining (Monk, p.115; Waugh, pp.103-5). (Tarnów lies about 60km East of Kracow, so the Goplana must have sailed first along the Vistula, then South along the river Dunajec, to reach there). (http://www.wittgensteinchronology.com/7.html Tuesday 25th August, 1914: In his private diary, LW notes that yesterday was a terrible day. In the evening the Goplana’s searchlight didn’t work, and when he tried to examine it, he was disturbed by the crew shouting, bawling, etc. He wanted to examine it more closely, but the platoon commander took it out of his hands. ‘It was horrible. I saw that there isn’t a single decent person in the whole crew’. He then wonders how to conduct himself in the future, should he tolerate this, or not? In the latter case, he muses, he would certainly wear out, but in the former case maybe not. He urges himself to keep himself together, and ends ‘God help me!’ (http://www.wittgensteinchronology.com/7.html) Wednesday 2nd September, 1914: In his private diary, LW notes that he has been on searchlight duty every night, with the exception of yesterday, and that he sleeps during the day. He seems thankful for this, since being on the night-shift means that he is thereby ‘deprived of the wickedness of my comrades’. He then reports that yesterday they heard a huge battle that had already been underway for 5 days. [This could have been the victory by the Austrian 1st army at the battle of Kraśnik or the victory of the Austrian 4th army at the battle of Komarów (or both)] He also notes that yesterday he masturbated ‘for the first time in 3 weeks’, being ‘almost unsensual’. He records that he works a little bit every day, but is too tired and distracted. But he also notes that he began reading Tolstoy's ‘Notes on the Gospels’. ‘A magnificent work. But it’s not what I expected.’ In his notebook entry, LW explains that at least part of what his dictum ‘Logic must take care of itself’ means is that in a certain sense it must be impossible to go wrong in logic. He counts this ‘an extremely profound and important insight’. Frege, he notes, had said that every well-formed sentence must make sense. But LW responds that every possible sentence is well-formed, and that if it doesn’t make sense this can only be because we have failed to give a meaning to one or more of its parts. (http://www.wittgensteinchronology.com/7.html) I’ll end with this poem by a poet who died in November 1914: On the Eastern Front by George Trakl The winter storm's mad organ playing is like the Volk's dark fury, the black-red tidal wave of onslaught, defoliated stars. Her features smashed, her arms silver, night calls to the dying men, beneath shadows of November's ash, ghost casualties heave. A spiky no-man's-land encloses the town. The moon hunts petrified women from their blood-spattered doorsteps. Grey wolves have forced the gates. Translation by John Greening. Source: http://www.worldwarone.it/search/label/Poets Expanded and edited, 10 November 2023. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed