Part 6: The Northwestern Bank - A Country Bank Goes to Town [Draft 1]

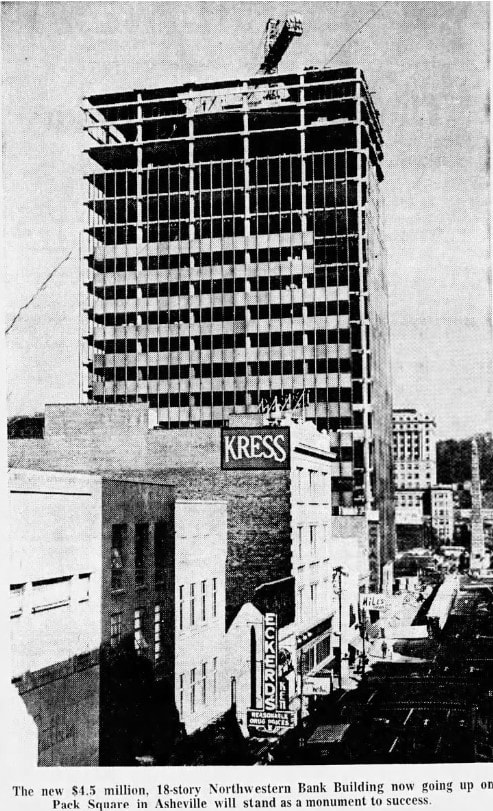

I don’t know the location or date of the picture. Though the resolution is poor, perhaps it was taken for bank PR purposes.

In April 1965, a few months after Daddy joined the bank and we moved to North Wilkesboro. The Winston-Salem Journal published a long, laudatory profile of Edwin Duncan, Sr., by Chester Davis. (1) The article implied that the success of the bank was the lengthened shadow of Duncan. Present at the creation of the bank in 1937, he served as executive vice president from its founding until 1958, when he became president. He was devoted to the economic development of the North Carolina mountains. Just five years later, the paper published a profile of Duncan’s son, newly selected as bank president while his father remained head of the holding company. (2) These profiles, explored in detail below, help us understand the culture of the bank that Daddy was joining and the context of the decisions that helped bring his life to a premature end. Another, more jaded view was provided by the bank itself, in 1976, in its suit against the IRS to recover back taxes, fines, and penalties. (3) As discussed below, the bank had to acknowledge that its “country bank” practices and controls were not sufficient to properly manage a company of its size. The evidence provided by the newspapers in 1976 suggests something more than poor controls, and this becomes even more evident in the accounts of the arrests and scandals in 1977.

In his profile of Edwin Duncan, Sr., reporter Davis describes him as “a big, hulking man with an amiable and handsome red face.” He has an unexpected laugh “for such a big man”—“a high pitched chuckle [that] is more like a giggle.” The idioms of the mountains “slip into his speech,” according to the reporter. His office is “bare of photographs and the other sentimental trophies of a lifetime with which may men like to surround themselves.” He has many business acquaintances, few “close personal friends.” “‘Any conversation with him,’” one of those friends says, “‘sooner or later will get around to profits and losses.’” Twelve years later, four years after Duncan’s death and in the time of scandals rocking the bank, the Winston-Salem Journal published another profile of Duncan, this one by Roy Thompson, a local columnist: Duncan “was a plain-talking man. Ask anybody who knew him to describe him, and you’ll hear some form of the verb ‘work’ in the first sentence.” (4) Still, according to Davis in the 1965 profile, he was “pleasant and often fascinating to talk to.” Another profile from the summer of 1977 relies on the recollections of a real estate developer, who describes how Duncan talked to him, potentially a new customer, at the beginning of his career. In 1960 the developer “gave up his trade as a plumber to go into home building” and needed money to grow:

“‘I had heard of Northwestern,’ … and I went to talk to Mr. (Edwin) Duncan (Sr.) himself. . . I could never go in and talk to the president of another bank. [Duncan] … put himself in a position to see a guy like myself. He and I just hit it off…. I think he had a lot of talent for this kind of thing; the was his strong point, no doubt about it. . . . I think he read the man more than he read his balance sheet. And he’d put it to you in a way that you’d feel, gosh, you just couldn’t let this man down. He just had so much faith in you that there was no way you could let him down . . . . .’” (5) Loans based on assessment of an individual rather than his balance sheet were called “character loans,” something that Duncan seems to have excelled at (6).

Duncan was as plain in appearance as in conversation: “he never learned to dress the way a banker was supposed to dress,” according to Roy Thompson. Thompson is being diplomatically general. When my sister was working at the bank she saw him enter the lobby one morning. His hair was disheveled, his suit rumpled, his trousers covered halfway to the knees in dried cow manure; he had evidently looked after his cattle before driving to work. She observed his nervous habit of chewing the end of his necktie. One day, while a friend of the family was at the bank on business, he saw Duncan walk into the lobby in a similar state. He told the bank official he was talking to that something ought to be done for that poor man. "Don't worry about him, sir; he owns the bank."

With a few exceptions, Duncan stuck to banking in his career, but the exceptions are notable: he served two terms in the State Senate and “twice on the State Banking Commission.” In 1960, the death of Carl Buchan left Lowe’s Hardware in a financial mess that, it was thought, could be resolved only through acquisition by a larger company and relocation. Duncan took over as president and chairman of the board and in four years “doubled the company’s sales and tripled its net worth,” assuring it could stay independent and remain headquartered in Wilkes County. (1)

Finally, Davis’s profile mentions three other key characteristics. First, Duncan was dedicated to the economic growth of northwest North Carolina; at the time, the bank was credited with the existence of forty-four companies in the area. As evidence of his “local patriotism,” a friend of Duncan told the reporter, “‘Edwin is as dedicated to this country as anybody who has been raised here.’” Second, “a lifetime friend” noted Duncan's “‘amazingly retentive memory. He not only recalls the smallest details but he possessed the great gift of fitting those details into a pattern and then acting on that pattern. He doesn't guess wrong often.’” Third, a long-time associate said, “‘He can see trouble coming and do something about it earlier and more constructively than any man I have ever been associated with.’”

Growth of the Bank

In looking at the description of the bank’s growth and culture depicted in these profiles, I will focus on indications of trouble in the light of later events—an unfair advantage I have over those living at the time.

In the twenty-eight years between 1937 and 1965, Northwestern grew from being the 27th largest bank in the state to the fifth. The growth was unplanned, Duncan says: “‘We take it as it comes.... We develop piecemeal.’” The bank expanded opportunistically (not a word he uses): since “‘a country bank can’t afford computers and it can’t offer its customers a line of credit sufficient to their needs,’” the bank must “‘expand and improve our services.” According to Duncan, “‘in six counties we serve, Northwestern is the only bank there is. In three of those counties we are the only lending institution of any kind,’” and there the bank serves “‘more like a building and loan association’” than a bank. (1)

But most of the growth occurred when Northwestern bought or merged with “‘small rural banks’” that typically “‘lack ... depth of leadership.’” How this strategy helped create Northwestern’s distinctive culture will be discussed below.

By the time of the interview, Duncan had realized that “‘we had to move to the cities. That's where our rural people are moving. Many of them will come to us because they know us. Many small businesses will come to us because we are tailed to serve their special needs.’” (1) But the move to the cities and areas beyond the North Carolina mountains may have been accelerated by the ambitions of Duncan’s son. Known by everyone as Booner, he joined the bank in 1957 and by 1964 he was a senior vice president. In addition to installment loans, he was responsible for branch operations. I don't know if his responsibilities then included expansion into new towns, but they probably did, since sometime after 1969 his subordinate, Gwyn Bowers, was put in charge of the bank's branch expansion and facilities. According to his obit, Booner “tried to overcome his father's desire that 'Northwestern never move outside the North Carolina mountains’” (6). At the time of the 1965 profile, the bank had 63 branches, most in or near the mountains, but some as far east as Burlington and Yanceyville. Booner became president of the bank in 1971 and by the time he was fired by the board in 1977, the bank had 140 branches from the mountains to Raleigh. All this is to say that behind the growth were competing visions and tactics, even if no grand vision guided the way.

The 1965 profile of the older Duncan discusses Northwestern’s project to build a “$4.5 million, 18-story Northwestern Bank building … on Park Square in Asheville,” a building that, the newspaper states, “will stand as a monument to success.” The ambition of the project—which in the future would create scandal, embarrassment, and lawsuits—belies Duncan’s main point, which we might call the opportunistic and organic growth of the bank. The project was conspicuous—it generated a lot of press, probably one of its purposes—and, as events would prove, it far exceeded the bank’s own need for office space in Asheville or its ability to lease office space to others. In his profile, Davis characterizes Duncan as “a man of modest ambitions and vaulting accomplishments,” but the Asheville bank suggests a larger ambition that at least on this occasion exceeded his ability to manage. (1)

Culture of the Bank

For Edwin Duncan, Sr., the bank began with the Bank of Sparta, founded in the early 20th century by his father. The customers were largely farmers. The banks that merged with the Bank of Sparta in 1937 to form Northwestern were also located in rural communities and were also designed to serve the needs of farmers and small-town businesses. In a profile of the younger Duncan published in early 1971, the reporter noted that the bank was “still heavy in farm financing. [In] the last rankings..., Northwestern Bank was listed as the 23rd largest farm bank in the nation and the largest farm bank in North Carolina” (2).

As we have seen, the older Duncan was accessible to customers and potential customers, and in the 1971 profile Booner makes a similar point: “farmers are down-to-earth people and don't like pretentiousness.... ‘If you notice outside there's not a wall of secretaries to block the entrances,’ he said of the bank's executive offices. ‘People wander in and talk to us sometimes without knowing who we are.’”

Edwin "Booner" Duncan, Jr.--John Byrd, "Edwin Duncan, Former Bank Chairman, Dies," Winston-Salem Journal, 7 March 1985, 1

The informal culture—everyone at the bank, from the mailroom to the C-Suite, called the younger Duncan “Booner,” much to the surprise of at least one visiting New York banker (7)—was reflected in decentralized decision-making. Perhaps because the bank began with the merger of several small banks and grew by merging with or purchasing other small banks, it promoted decision-making at the local level. In the 1965 profile, the older Duncan stated, “‘We believe that local officers and local boards of directors have a better understanding of their customers and their banking needs than home office personnel.... We don't bank by the book.’” (1) In his 1971 profile, the younger Duncan said, “‘We like to think of ourselves as an association of small banks.... As long as our managers do a good job and show the profit we expect of them, they are largely on their own.’” The reporter found officials of other banks who corroborated this account; they even said that Northwestern branches sometimes competed against each other for business. (2)

More often than not, Northwestern’s local boards and management had been associated with the smaller bank merged into Northwestern. Leaving them with decision-making authority was a way to attach their loyalty and their interests to their new employer. A manager who left for a competitor could take customers with him (most if not all were men). Years later, it became apparent that this desire to hang on to influential local talent sometimes led the bank to commit questionable, probably illegal practices. In the mid-1960s, payments totaling $550,000 were made to four men working for banks being acquired by Northwestern. The payments were designed to “secure the employment of key management personnel and to prevent them from leaving the bank and competing with it in the community following the bank’s acquisition.” . If disclosed to the FDIC, the payments would have been prohibited and the mergers blocked. To conceal the transactions from the FDIC, the payments were made through the Northwest Finance Company, a company owned personally by Duncan and other high bank officials. The payments were probably illegal, but by the time they were disclosed, in 1974, they were well past the five-year statute of limitations. (8)

This practice—and the effective way it was concealed from regulators—is evidence of two related cultural traits: clever tactics and willingness to skirt laws and regulations. I wonder if the government’s discovery of these tricks was foreseen by the older Duncan, with his vaunted ability to see trouble coming; if so, his stratagems to prevent discovery failed not long after his death. The cleverness was evident in 1964, when, to raise capital, Northwestern became the first bank in the state to issue debentures—unsecured, “long-range promissory notes,” as the newspaper described them—rather than issuing stock, a much more common way of raising capital. Debentures had advantages over issuing new shares: they did not dilute the value of current shares and the “‘interest on debentures is [tax]-deductible.’” Issuing the debentures required a rule change by the State Banking Commission. (9) To achieve its goals, the bank engaged in relatively sophisticated political and financial maneuvering, yet its country bank roots were still evident, if we can believe the bank. In a lawsuit against the IRS roughly ten years later, the bank stated: “‘It must be remembered that [in the late 1960s and early 1970s] there was little opportunity for bank management to learn about tax planning…. [T]here was no certified public accountant on the bank’s staff, there was little association with an independent public accounting firm and the advice of lawyers was sought ‘very little.’” (10) The bank now used its carefully polished image as a country bank to explain away control issues: “‘The Northwestern Bank was a country bank as it was run like one. . .and did not depend upon careful, polished legal documents.’” (11)

The lack of controls is evident in a practice adopted by the bank in 1968-1970, and possibly further back: in lieu of entries in the company books, bank personnel would cut cashier’s checks against the company’s funds; the only audit trail was usually the name of the cashier who signed the check. On discovering this practice, the IRS declared the checks as unreported income and collected back taxes along with significant fines and penalties. In its 1976 suit against the IRS to recover the funds, the bank argued that the practice was not inherently wrong, but only evidence of how the bank’s growth had overwhelmed its systems and practices. An experienced accountant I know has told me that this practice may well have been adopted to conceal questionable transactions. I think this likely, though in the news accounts I’ve seen, no connection is made between the cashier’s checks and the questionable business arrangements and cash flows that came under scrutiny, for example, the divergence of insurance commissions from the bank to a company owned by Edwin Duncan, Jr., Certified Check and Title (see below for more). In preparation to reclaim the money from the IRS, the bank retained an audit firm that took eighteen months to document the cashier’s checks and update the company’s books. (11)

As another indication of the lack of controls, the company did not name a general counsel until after Booner’s dismissal by the board in 1977. The lawyer who came closest to filling that role during Booner’s term as president, Jack T. Hamilton of Charlotte, was more a crony—a loyal and trusted friend—than a company lawyer. (12) In the country bank tradition, the Duncans, father and son, surrounded themselves with friends and family members. Benevolent nepotism is a theme of Booner’s obituaries in 1985, at least those written under the influence of his family. One obituary quotes an interview with the older Duncan: “Edwin Duncan Sr. made no secret of his tendency toward nepotism—or ‘well-placed family members’ …. He said there was a place at Northwestern for every ‘competent family member,’ and many of them worked there.” (13) When I worked in the Time Payment Department, an older member of the Duncan family occasionally spent a few hours in the department. She must have had some work-related reason for being there, but I remember her only because she often sat at a desk clipping bond coupons, coupons she’d then submit to receive the interest. This was new and fascinating to me, and it seemed absurd, no doubt the reason I remember it.

Booner’s daughter, Katherine Woodruff, said, “‘My grandfather and daddy believed in nepotism.... They saw the bank as a small bank that served Northwest North Carolina. They knew most of the families in Northwest North Carolina, and they promoted families they knew at that bank.’” (6) Along with the network of family and friends, Booner “inherited his father's intense personal loyalties and his enemies,” an extension of the older man’s local patriotism. These enemies included notably the IRS; according to the family, Booner and his father were engaged “in a long family dispute” with the IRS. In 1966, the bank had recovered more than $200,000 from the IRS, and in glee the older Duncan posted a copy of the check in the lobby of the home office. The family thought that the IRS audit launched in September 1971 was a continuation of the feud.

Management by cronies in a company with weak accounting controls made it easy for top management to privately profit from assets owned by shareholders. A perfect example is the relationship between the bank and Certified Title and Check (CC&T). I’ve already mentioned my shock when I found Daddy’s involvement with CC&T. The company was owned in entirety by the younger Duncan and held in trust for his children. Although it was not part of the Northwestern family of companies, its officers and employees, including Daddy, worked for the bank or related companies, and they did much, if not all, of CC&T’s work. I suspect that providing extra income to trusted bank employees was another expression of the Duncans’ nepotism. Daddy was involved in CC&T’s business of buying and reselling heavy construction equipment. More important, he was a central player in the shady scheme of financing purchases through loans nominally made to Julius Womble but actually issued for the benefit of CC&T, a scheme that the government thought was intended to bypass state laws limiting the amount bank officers could borrow from their own bank (14). Daddy was also involved in some way in CC&T’s unsuccessful business in selling Costa Rican cigars in the US.

However, by far the most important use of CC&T was to finance a small fleet of company airplanes in a way that hid the fleet from the board and regulators. (Daddy knew about this and occasionally used the planes, including a trip to the Caymans and Costa Rica, but I don’t know if he was otherwise involved.) The scheme worked something like this: when a consumer loan was issued, the loan officer—who had to be licensed to sell insurance in the state—offered the customer the option of purchasing insurance policies to make payments in the event of the customer’s death (known as credit life insurance) or disability (credit accident and health insurance). One newspaper account states that, in some cases, the insurance was required to close the loans (10). But my recollection is that the insurance was optional, hence Daddy’s advice to me (which I clearly remember) never to buy it. Sales of the policies generated commissions, and though some commissions seem to have been paid to loan officers, most were diverted to lease (or purchase) and maintain the aircraft.

At first, the commissions were paid directly to the bank for this purpose, but in 1969 (when there were six planes in the fleet), management learned that the State Banking Commission and IRS would question the payment of commissions to the bank, so the payments were diverted to CC&T. The payments were washed through “insurance checking accounts” that were not closed annually and in that way were hidden from the board, stockholders, and regulators. According to the FBI, at least $2.5 million in commissions were diverted in this way. Like many practices that later came under scrutiny, this sleight-of-hand began when Edwin Duncan, Sr., was still president of the bank, but it was the son who inherited the practice and the wrath of the government. (15)

More often than not, Northwestern’s local boards and management had been associated with the smaller bank merged into Northwestern. Leaving them with decision-making authority was a way to attach their loyalty and their interests to their new employer. A manager who left for a competitor could take customers with him (most if not all were men). Years later, it became apparent that this desire to hang on to influential local talent sometimes led the bank to commit questionable, probably illegal practices. In the mid-1960s, payments totaling $550,000 were made to four men working for banks being acquired by Northwestern. The payments were designed to “secure the employment of key management personnel and to prevent them from leaving the bank and competing with it in the community following the bank’s acquisition.” . If disclosed to the FDIC, the payments would have been prohibited and the mergers blocked. To conceal the transactions from the FDIC, the payments were made through the Northwest Finance Company, a company owned personally by Duncan and other high bank officials. The payments were probably illegal, but by the time they were disclosed, in 1974, they were well past the five-year statute of limitations. (8)

This practice—and the effective way it was concealed from regulators—is evidence of two related cultural traits: clever tactics and willingness to skirt laws and regulations. I wonder if the government’s discovery of these tricks was foreseen by the older Duncan, with his vaunted ability to see trouble coming; if so, his stratagems to prevent discovery failed not long after his death. The cleverness was evident in 1964, when, to raise capital, Northwestern became the first bank in the state to issue debentures—unsecured, “long-range promissory notes,” as the newspaper described them—rather than issuing stock, a much more common way of raising capital. Debentures had advantages over issuing new shares: they did not dilute the value of current shares and the “‘interest on debentures is [tax]-deductible.’” Issuing the debentures required a rule change by the State Banking Commission. (9) To achieve its goals, the bank engaged in relatively sophisticated political and financial maneuvering, yet its country bank roots were still evident, if we can believe the bank. In a lawsuit against the IRS roughly ten years later, the bank stated: “‘It must be remembered that [in the late 1960s and early 1970s] there was little opportunity for bank management to learn about tax planning…. [T]here was no certified public accountant on the bank’s staff, there was little association with an independent public accounting firm and the advice of lawyers was sought ‘very little.’” (10) The bank now used its carefully polished image as a country bank to explain away control issues: “‘The Northwestern Bank was a country bank as it was run like one. . .and did not depend upon careful, polished legal documents.’” (11)

The lack of controls is evident in a practice adopted by the bank in 1968-1970, and possibly further back: in lieu of entries in the company books, bank personnel would cut cashier’s checks against the company’s funds; the only audit trail was usually the name of the cashier who signed the check. On discovering this practice, the IRS declared the checks as unreported income and collected back taxes along with significant fines and penalties. In its 1976 suit against the IRS to recover the funds, the bank argued that the practice was not inherently wrong, but only evidence of how the bank’s growth had overwhelmed its systems and practices. An experienced accountant I know has told me that this practice may well have been adopted to conceal questionable transactions. I think this likely, though in the news accounts I’ve seen, no connection is made between the cashier’s checks and the questionable business arrangements and cash flows that came under scrutiny, for example, the divergence of insurance commissions from the bank to a company owned by Edwin Duncan, Jr., Certified Check and Title (see below for more). In preparation to reclaim the money from the IRS, the bank retained an audit firm that took eighteen months to document the cashier’s checks and update the company’s books. (11)

As another indication of the lack of controls, the company did not name a general counsel until after Booner’s dismissal by the board in 1977. The lawyer who came closest to filling that role during Booner’s term as president, Jack T. Hamilton of Charlotte, was more a crony—a loyal and trusted friend—than a company lawyer. (12) In the country bank tradition, the Duncans, father and son, surrounded themselves with friends and family members. Benevolent nepotism is a theme of Booner’s obituaries in 1985, at least those written under the influence of his family. One obituary quotes an interview with the older Duncan: “Edwin Duncan Sr. made no secret of his tendency toward nepotism—or ‘well-placed family members’ …. He said there was a place at Northwestern for every ‘competent family member,’ and many of them worked there.” (13) When I worked in the Time Payment Department, an older member of the Duncan family occasionally spent a few hours in the department. She must have had some work-related reason for being there, but I remember her only because she often sat at a desk clipping bond coupons, coupons she’d then submit to receive the interest. This was new and fascinating to me, and it seemed absurd, no doubt the reason I remember it.

Booner’s daughter, Katherine Woodruff, said, “‘My grandfather and daddy believed in nepotism.... They saw the bank as a small bank that served Northwest North Carolina. They knew most of the families in Northwest North Carolina, and they promoted families they knew at that bank.’” (6) Along with the network of family and friends, Booner “inherited his father's intense personal loyalties and his enemies,” an extension of the older man’s local patriotism. These enemies included notably the IRS; according to the family, Booner and his father were engaged “in a long family dispute” with the IRS. In 1966, the bank had recovered more than $200,000 from the IRS, and in glee the older Duncan posted a copy of the check in the lobby of the home office. The family thought that the IRS audit launched in September 1971 was a continuation of the feud.

Management by cronies in a company with weak accounting controls made it easy for top management to privately profit from assets owned by shareholders. A perfect example is the relationship between the bank and Certified Title and Check (CC&T). I’ve already mentioned my shock when I found Daddy’s involvement with CC&T. The company was owned in entirety by the younger Duncan and held in trust for his children. Although it was not part of the Northwestern family of companies, its officers and employees, including Daddy, worked for the bank or related companies, and they did much, if not all, of CC&T’s work. I suspect that providing extra income to trusted bank employees was another expression of the Duncans’ nepotism. Daddy was involved in CC&T’s business of buying and reselling heavy construction equipment. More important, he was a central player in the shady scheme of financing purchases through loans nominally made to Julius Womble but actually issued for the benefit of CC&T, a scheme that the government thought was intended to bypass state laws limiting the amount bank officers could borrow from their own bank (14). Daddy was also involved in some way in CC&T’s unsuccessful business in selling Costa Rican cigars in the US.

However, by far the most important use of CC&T was to finance a small fleet of company airplanes in a way that hid the fleet from the board and regulators. (Daddy knew about this and occasionally used the planes, including a trip to the Caymans and Costa Rica, but I don’t know if he was otherwise involved.) The scheme worked something like this: when a consumer loan was issued, the loan officer—who had to be licensed to sell insurance in the state—offered the customer the option of purchasing insurance policies to make payments in the event of the customer’s death (known as credit life insurance) or disability (credit accident and health insurance). One newspaper account states that, in some cases, the insurance was required to close the loans (10). But my recollection is that the insurance was optional, hence Daddy’s advice to me (which I clearly remember) never to buy it. Sales of the policies generated commissions, and though some commissions seem to have been paid to loan officers, most were diverted to lease (or purchase) and maintain the aircraft.

At first, the commissions were paid directly to the bank for this purpose, but in 1969 (when there were six planes in the fleet), management learned that the State Banking Commission and IRS would question the payment of commissions to the bank, so the payments were diverted to CC&T. The payments were washed through “insurance checking accounts” that were not closed annually and in that way were hidden from the board, stockholders, and regulators. According to the FBI, at least $2.5 million in commissions were diverted in this way. Like many practices that later came under scrutiny, this sleight-of-hand began when Edwin Duncan, Sr., was still president of the bank, but it was the son who inherited the practice and the wrath of the government. (15)

The Asheville building under construction--Chester Davis, "Faith in the Future--Banker Ed Duncan, Symbol of Northwestern N.C. Growth," Winston-Salem Journal, 4 April 1965, 57.

The Asheville bank building project, predicted in the profile of the older Duncan to become “a monument to success,” became something else entirely. In late 1975, a stockholder of the holding corporation, Northwestern Financial Corp., sued the company “alleging that top Northwestern officials had been using a company controlled by themselves”—that is, the similarly named Northwestern Finance Co.—“to rake off profits from the corporation and Northwestern Bank.” Unlike CC&T, the principal here was the older Duncan, but, like CC&T, “the company had no office, no employes, has consequently paid no salary and has incurred no administrative expenses,” or so the suit alleged: “the bank supplied all of these.” (16)

In the case of the Asheville building, the project got in trouble when the developer went bankrupt. To help save the project, “the bank leased from a finance company subsidiary, Northwestern Bank Building, Inc...., floors 7 to 11 in the building... although the bank had no use for the space”; the bank also “paid ground rent to” another subsidiary of Northwestern Finance. The rent was paid, according to the bank, to prevent bad publicity in the Asheville area. Northwestern Finance—again, a company unrelated to the bank but controlled by the older Duncan—apparently financed the project, but it was saved from disaster by the bank: the finance company “ended up owning the building,” while the bank and its shareholders bore the risks and “lost a substantial sum of money.”

There was at least one other similar project, the building of a dam in Colorado, where risk was shifted by the finance company to the bank; the lawsuit alleged that the $10 million in losses borne by the bank translated to a profit of $100,000 for Duncan’s finance company. Details of this deal were not revealed to regulators or even the board till after the older Duncan’s death. In these arrangements, Duncan stood to personally profit from the bank’s losses, though whether he did, and to what extent, I do not know. The judge set aside stock valued $750,000 in anticipation of settling the shareholders' suit, perhaps an indication of how much he thought the finance company had profited at the expense of the bank and its shareholders (17).

This was the company my father joined in 1965, the culture that in September 1971 expected him to break the law in loyalty to the bank and especially to the Edwin Duncans.

*****

I also worked at the bank for several short stints during summers and after my return from my mission.

In his February 1971 profile, Edwin Duncan, Jr., is described as sitting in his office in downtown North Wilkesboro. He shifted a bit in his chair and pointed out a side street that, he said, had once been the center of trade in North Wilkesboro. He was looking out on Tenth Street, then with only a couple of blocks of businesses, including a bar and a pool room; it was known as a street to avoid after dark on the weekends.

But during the Second World War, according to my father, you could buy any item you needed Tenth, no matter how severely rationed. I don't remember now if he used the term “black market,” but that was how I understood him. One of my occasional jobs was to walk loan papers around to nearby members of the loan committee. So far as I could tell, not every loan was treated this way, but I don’t remember why some loans required approval by the committee; perhaps I never knew. I vaguely remember two members of the loan committee. One managed the old-fashioned department store on the corner of D Street and Tenth Street, where I’d gone more than once to buy blue jeans. It was a short walk from the bank. The other member of the committee was an older, heavy man named Frank, whose store was even closer to the bank, near the corner of 10th and B Street (the town's main street). His store--a wholesale grocery, as I've discovered after a bit of research--was dark and full of a jumble of things; I vaguely remember salt-cured hams hanging from the walls and bags of feed stacked on the floor. It was not, to my young eyes, impressive as a business, and I wondered why the owner should serve on the loan committee. Daddy said he was one of the men you went to during the war to get whatever you wanted. I supposed that along the way he had accumulated property and investments and useful connections.

There isn’t much to this memory, beyond the pleasure in its unexpected return to consciousness, except this: the knowledge of shady behavior by an older man filled me with a certain conceit and unearned superiority. In a casual way, I passed on my new-found knowledge to my boss, expecting her to be amused or impressed by my inside knowledge. She was an extremely dignified and put-together woman, perhaps around forty-five years old, with extensive ties to the community. Her husband was a farmer, I think, and she came from a family that owned a Main Street jewelry store, where she often worked after banking hours and on the weekends. She was upset and angry with me. “That’s not true!” she said. “You shouldn’t be repeating such things.” Though I thought Daddy’s information was probably accurate, her rebuke of my idle gossip was just. I have often wondered how much she was affected by the many scandals that rocked the bank in 1976 and 1977.

I'm an excellent example of Northwestern's nepotism at work. I got the job only because my father was a vice president. I believe I replaced an older woman who had quit or perhaps retired in the not distant past, but the department could have gotten along quite well without me. My primary task was taking payments on installment loans. The busy time was Friday afternoon, when the workers at a nearby furniture plant and other businesses cashed their paychecks and made their car payments. The checks were small and on occasion the car payment was relatively large, usually when a worker had bought, for himself or his son, a muscle car. I must have taken at least a few payments from women, but all I remember is the men, including an African American barber who delighted in the unexpected pronunciation of his name. He asked me to pronounce the name, McEachin, as it was spelled on the payment coupon. I said, muh-KEACH-un. He laughed and said it was muh-KAY-hern.

My other main task was helping the insurance clerk, a delightful woman named Arlene. Banks require that cars they finance be covered by collision insurance. One of Arlene’s jobs was to obtain endorsements of coverage from the insurance companies and match them with the loan papers (all this was done in paper). She always had a stack of endorsements she could not match with loans, and when my work as a teller was slow, I was responsible for matching endorsements with loans, including paid-off loans. (If the loan had been paid off, we did not need the endorsement, so we could discard it.) One of the problems was that, in our files, the customers’ names were often spelled wrong. Another was that we received endorsements in error, so there was no matching loan. It was tedious work, but Arlene was fun to work with. She was deeply devoted to her family, including a brother who was severely injured when he was changing a truck tire. She was in the choir at her church and she often shared the sheet much of the Gospel songs she was learning. I can’t read music, but since I my childhood I’ve enjoyed Southern Gospel music, so I appreciated the lyrics. Sad to say, it never occurred to me to go to church with Arlene and hear her choir perform. Arlene used to say that, if she didn't do something right or on time, "my name will be mud," so I took to calling her Mud Spears on occasion. I hope she realized it was out of affection.

I was a “family and friends” hire, but I did my work and I enjoyed my relationship with my coworkers, including many I’ve not mentioned here. But it became a painful experience on the day I accidentally saw one of my coworker’s pay stubs. She was far more experienced at the job and brought more value to the bank, and she was helping support a family, but I discovered that I was being paid significantly more. This was a mortifying revelation.

Posted 26 March 2024, updated 28 March 2024, 12 April 2024, 5 May 2024. Please send comments, corrections, and questions to [email protected].

The Asheville bank building project, predicted in the profile of the older Duncan to become “a monument to success,” became something else entirely. In late 1975, a stockholder of the holding corporation, Northwestern Financial Corp., sued the company “alleging that top Northwestern officials had been using a company controlled by themselves”—that is, the similarly named Northwestern Finance Co.—“to rake off profits from the corporation and Northwestern Bank.” Unlike CC&T, the principal here was the older Duncan, but, like CC&T, “the company had no office, no employes, has consequently paid no salary and has incurred no administrative expenses,” or so the suit alleged: “the bank supplied all of these.” (16)

In the case of the Asheville building, the project got in trouble when the developer went bankrupt. To help save the project, “the bank leased from a finance company subsidiary, Northwestern Bank Building, Inc...., floors 7 to 11 in the building... although the bank had no use for the space”; the bank also “paid ground rent to” another subsidiary of Northwestern Finance. The rent was paid, according to the bank, to prevent bad publicity in the Asheville area. Northwestern Finance—again, a company unrelated to the bank but controlled by the older Duncan—apparently financed the project, but it was saved from disaster by the bank: the finance company “ended up owning the building,” while the bank and its shareholders bore the risks and “lost a substantial sum of money.”

There was at least one other similar project, the building of a dam in Colorado, where risk was shifted by the finance company to the bank; the lawsuit alleged that the $10 million in losses borne by the bank translated to a profit of $100,000 for Duncan’s finance company. Details of this deal were not revealed to regulators or even the board till after the older Duncan’s death. In these arrangements, Duncan stood to personally profit from the bank’s losses, though whether he did, and to what extent, I do not know. The judge set aside stock valued $750,000 in anticipation of settling the shareholders' suit, perhaps an indication of how much he thought the finance company had profited at the expense of the bank and its shareholders (17).

This was the company my father joined in 1965, the culture that in September 1971 expected him to break the law in loyalty to the bank and especially to the Edwin Duncans.

*****

I also worked at the bank for several short stints during summers and after my return from my mission.

In his February 1971 profile, Edwin Duncan, Jr., is described as sitting in his office in downtown North Wilkesboro. He shifted a bit in his chair and pointed out a side street that, he said, had once been the center of trade in North Wilkesboro. He was looking out on Tenth Street, then with only a couple of blocks of businesses, including a bar and a pool room; it was known as a street to avoid after dark on the weekends.

But during the Second World War, according to my father, you could buy any item you needed Tenth, no matter how severely rationed. I don't remember now if he used the term “black market,” but that was how I understood him. One of my occasional jobs was to walk loan papers around to nearby members of the loan committee. So far as I could tell, not every loan was treated this way, but I don’t remember why some loans required approval by the committee; perhaps I never knew. I vaguely remember two members of the loan committee. One managed the old-fashioned department store on the corner of D Street and Tenth Street, where I’d gone more than once to buy blue jeans. It was a short walk from the bank. The other member of the committee was an older, heavy man named Frank, whose store was even closer to the bank, near the corner of 10th and B Street (the town's main street). His store--a wholesale grocery, as I've discovered after a bit of research--was dark and full of a jumble of things; I vaguely remember salt-cured hams hanging from the walls and bags of feed stacked on the floor. It was not, to my young eyes, impressive as a business, and I wondered why the owner should serve on the loan committee. Daddy said he was one of the men you went to during the war to get whatever you wanted. I supposed that along the way he had accumulated property and investments and useful connections.

There isn’t much to this memory, beyond the pleasure in its unexpected return to consciousness, except this: the knowledge of shady behavior by an older man filled me with a certain conceit and unearned superiority. In a casual way, I passed on my new-found knowledge to my boss, expecting her to be amused or impressed by my inside knowledge. She was an extremely dignified and put-together woman, perhaps around forty-five years old, with extensive ties to the community. Her husband was a farmer, I think, and she came from a family that owned a Main Street jewelry store, where she often worked after banking hours and on the weekends. She was upset and angry with me. “That’s not true!” she said. “You shouldn’t be repeating such things.” Though I thought Daddy’s information was probably accurate, her rebuke of my idle gossip was just. I have often wondered how much she was affected by the many scandals that rocked the bank in 1976 and 1977.

I'm an excellent example of Northwestern's nepotism at work. I got the job only because my father was a vice president. I believe I replaced an older woman who had quit or perhaps retired in the not distant past, but the department could have gotten along quite well without me. My primary task was taking payments on installment loans. The busy time was Friday afternoon, when the workers at a nearby furniture plant and other businesses cashed their paychecks and made their car payments. The checks were small and on occasion the car payment was relatively large, usually when a worker had bought, for himself or his son, a muscle car. I must have taken at least a few payments from women, but all I remember is the men, including an African American barber who delighted in the unexpected pronunciation of his name. He asked me to pronounce the name, McEachin, as it was spelled on the payment coupon. I said, muh-KEACH-un. He laughed and said it was muh-KAY-hern.

My other main task was helping the insurance clerk, a delightful woman named Arlene. Banks require that cars they finance be covered by collision insurance. One of Arlene’s jobs was to obtain endorsements of coverage from the insurance companies and match them with the loan papers (all this was done in paper). She always had a stack of endorsements she could not match with loans, and when my work as a teller was slow, I was responsible for matching endorsements with loans, including paid-off loans. (If the loan had been paid off, we did not need the endorsement, so we could discard it.) One of the problems was that, in our files, the customers’ names were often spelled wrong. Another was that we received endorsements in error, so there was no matching loan. It was tedious work, but Arlene was fun to work with. She was deeply devoted to her family, including a brother who was severely injured when he was changing a truck tire. She was in the choir at her church and she often shared the sheet much of the Gospel songs she was learning. I can’t read music, but since I my childhood I’ve enjoyed Southern Gospel music, so I appreciated the lyrics. Sad to say, it never occurred to me to go to church with Arlene and hear her choir perform. Arlene used to say that, if she didn't do something right or on time, "my name will be mud," so I took to calling her Mud Spears on occasion. I hope she realized it was out of affection.

I was a “family and friends” hire, but I did my work and I enjoyed my relationship with my coworkers, including many I’ve not mentioned here. But it became a painful experience on the day I accidentally saw one of my coworker’s pay stubs. She was far more experienced at the job and brought more value to the bank, and she was helping support a family, but I discovered that I was being paid significantly more. This was a mortifying revelation.

Posted 26 March 2024, updated 28 March 2024, 12 April 2024, 5 May 2024. Please send comments, corrections, and questions to [email protected].

The last Pintor cigar box I own. It has darkened with age (I lightened this photo to make it easier to see) and has lost the distinctive and pleasant tobacco aroma it had for many years. The tobacco was reputedly grown from seed smuggled out of Cuba.

NOTES

Note 1: Chester Davis, “Faith in the Future—Banker Ed Duncan, Symbol of Northwestern N.C. Growth,” Winston Salem Journal, 4 April 1965, 57.

Note 2: Conrad Paysour, “’Country Bank’ Makes It In The Cities,” Greensboro News and Record (21 Feb 1971, 65)

Note 3: “Controlled by Duncan: Company Got Commissions,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1

Note 4: Roy Thompson, “Bank’s Problems Can’t Erase Its Accomplishments,” Winston-Salem Journal, 21 July 1977

Note 5: Tom Sieg, “‘And I Still Feel Like Northwestern Is a Man’s Bank,'” Sentinel, 30 July 1977, 1)

Note 6: John Byrd, “Edwin Duncan, Former Bank Chairman, Dies,” Winston-Salem Journal, 7 Mar 1985, 1).

Note 7: W.H. Scarborough, “Northwestern Bank: Our Basic Business Is Still the Little Man,” Winston-Salem Journal, 3 Oct 1976, 13. “Booner” was how the younger Duncan’s childhood pronunciation of “Junior.” Scarborough thought “the very junior clerk” called him “Booney.”

Note 8: Pat Stith, “Northwestern Hid Merger Payments from FDIC,” News and Observer, 31 July 1977, 7; “Northwestern Made Payments to Bankers,” Sentinel, 1 Aug 1977, 13, 14.)

Note 9: Harold Ellison, “Bank Sells $5 Million in Debentures,” Winston-Salem Journal, 13 May 1964, 12

Note 10: “Controlled by Duncan: Company Got Commissions,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1, 2).

Note 11: “Northwestern Acknowledged Shortcomings,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1-2).

Note 12: “Lawyer Back on Stand in Northwestern Probe,” Sentinel, 2 Aug 1977, 2).

Note 13: Bill East, “Banker Edwin Duncan Dies at 57,” Sentinel, 7 Mar 1985, 16. The quotations from the older Duncan are from an interview I have been unable to locate.

Note 14: David Bailey, “Duncan Faces 3 Charges in File Here This Week,” Winston-Salem Journal, 25 Sep 1977, 17, 19. Neither Duncan nor anyone else was indicted, but the information was divulged by an FBI agent in Duncan’s sentencing hearing.

Note 15: “IRS Urged Indictment of Northwestern Bank,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1, 2; Tom Sieg and Mark Wright, “SEC Data Fills Gaps In Northwestern Case,” Sentinel, 27 Jul 1977, 1, 11; “Controlled by Duncan: Company Got Commissions,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1; Mark Wright, “Witness: Premiums Taken,” Sentinel, 11 Nov 1977, 1, 2.

Note 16: David Bailey, “Duncan Faces 3 Charges in File Here This Week,” Winston-Salem Journal, 25 Sep 1977, 17, 19; “IRS Urged Indictment of Northwestern Bank,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1, 2; Tom Sieg, “Court May Allow Cut in Stock Payment,” Sentinel, 28 Oct 1976, 17.

Note 17: Tom Sieg, “Court May Allow Cut in Stock Payment”

Note 1: Chester Davis, “Faith in the Future—Banker Ed Duncan, Symbol of Northwestern N.C. Growth,” Winston Salem Journal, 4 April 1965, 57.

Note 2: Conrad Paysour, “’Country Bank’ Makes It In The Cities,” Greensboro News and Record (21 Feb 1971, 65)

Note 3: “Controlled by Duncan: Company Got Commissions,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1

Note 4: Roy Thompson, “Bank’s Problems Can’t Erase Its Accomplishments,” Winston-Salem Journal, 21 July 1977

Note 5: Tom Sieg, “‘And I Still Feel Like Northwestern Is a Man’s Bank,'” Sentinel, 30 July 1977, 1)

Note 6: John Byrd, “Edwin Duncan, Former Bank Chairman, Dies,” Winston-Salem Journal, 7 Mar 1985, 1).

Note 7: W.H. Scarborough, “Northwestern Bank: Our Basic Business Is Still the Little Man,” Winston-Salem Journal, 3 Oct 1976, 13. “Booner” was how the younger Duncan’s childhood pronunciation of “Junior.” Scarborough thought “the very junior clerk” called him “Booney.”

Note 8: Pat Stith, “Northwestern Hid Merger Payments from FDIC,” News and Observer, 31 July 1977, 7; “Northwestern Made Payments to Bankers,” Sentinel, 1 Aug 1977, 13, 14.)

Note 9: Harold Ellison, “Bank Sells $5 Million in Debentures,” Winston-Salem Journal, 13 May 1964, 12

Note 10: “Controlled by Duncan: Company Got Commissions,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1, 2).

Note 11: “Northwestern Acknowledged Shortcomings,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1-2).

Note 12: “Lawyer Back on Stand in Northwestern Probe,” Sentinel, 2 Aug 1977, 2).

Note 13: Bill East, “Banker Edwin Duncan Dies at 57,” Sentinel, 7 Mar 1985, 16. The quotations from the older Duncan are from an interview I have been unable to locate.

Note 14: David Bailey, “Duncan Faces 3 Charges in File Here This Week,” Winston-Salem Journal, 25 Sep 1977, 17, 19. Neither Duncan nor anyone else was indicted, but the information was divulged by an FBI agent in Duncan’s sentencing hearing.

Note 15: “IRS Urged Indictment of Northwestern Bank,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1, 2; Tom Sieg and Mark Wright, “SEC Data Fills Gaps In Northwestern Case,” Sentinel, 27 Jul 1977, 1, 11; “Controlled by Duncan: Company Got Commissions,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1; Mark Wright, “Witness: Premiums Taken,” Sentinel, 11 Nov 1977, 1, 2.

Note 16: David Bailey, “Duncan Faces 3 Charges in File Here This Week,” Winston-Salem Journal, 25 Sep 1977, 17, 19; “IRS Urged Indictment of Northwestern Bank,” Winston-Salem Journal, 28 Nov 1976, 1, 2; Tom Sieg, “Court May Allow Cut in Stock Payment,” Sentinel, 28 Oct 1976, 17.

Note 17: Tom Sieg, “Court May Allow Cut in Stock Payment”