|

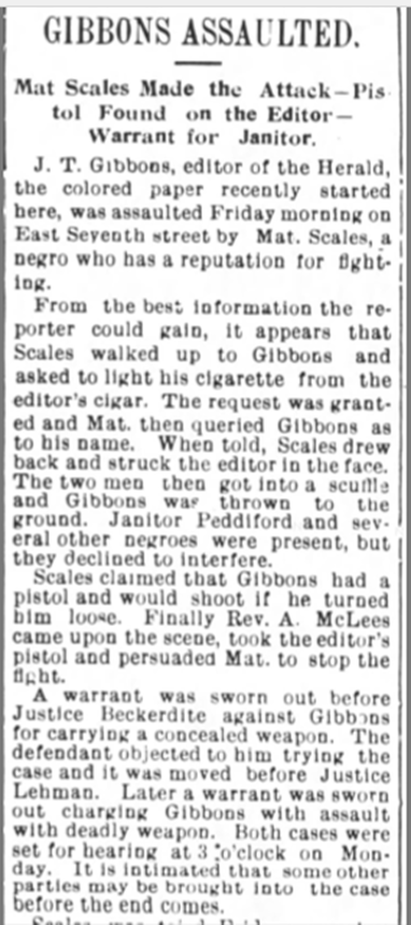

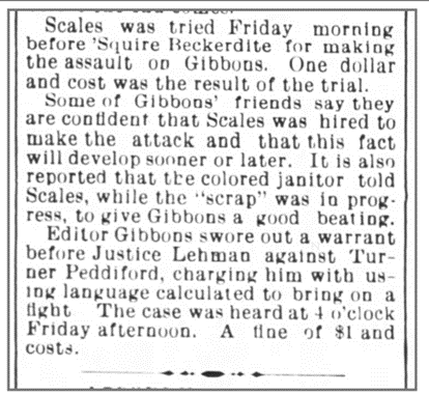

Tuttle defender in focus: Mat Scales To think clearly in human terms you have to be impelled by a poem.—Les Murray  The Western Sentinel (7 Apr 1898, 1) The scope of this study is so small, I might perhaps be excused from concerning myself with methodology. But there are three points that I think deeply important to the study of history and even our lives, especially in a time where life and liberty seem threatened on many sides. Openness to the future To make the first point, I quote from Clive James’s essay on Golo Mann, the great German historian: “In his Zeiten und Figuren (Times and Figures) (1979), Golo Mann expounded his key concept of Offenheit nach der Zukunft hin—openness to the future. He didn’t just mean it as a desirable trait of personality but as a necessary qualification for the historian. By an effort of the imagination, the historian must put himself back into a present where the future has not yet happened, even though he is looking back at it through the past. If a narrator knows the future of his hero, he, the narrator, ‘is bound to tinge even the simplest narrative with  irony.' Succumbing too easily to the ironic mode is a cheap way of being Tacitus. The true high worth of Tacitus depended on his being always aware that tragic events had been the result of accidents and bad decisions, and the depth of the tragedy lay in the fact that the accidents need not have happened and the decisions might have been good. In a predetermined world there would be no tragedy, only fate. With his revered Tacitus as an example, Golo Mann was able to form the view that fatalism and frivolity were closely allied: to be serious about history, you had seriously to believe that things might have been otherwise.” (emphasis added; Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts, pp. 423-424, Norton, Kindle Edition) To believe that a political trend is inevitable makes it hard to resist, especially in any organized, effective way; the aura of inevitability makes resistance seem a fool’s errand. Some will fight for lost causes, but when a catastrophe is thought to be unavoidable, many will look for a way to navigate their own way through, let the devil take the hindmost. As a disaster develops, this may become the only choice, but I’m talking about those earlier moments when hope is still realistic and inevitability is a construct of demagoguery. Imagination as method The second methodological point is the importance of imagination in understanding the truth of history. As Simon Leys notes, “At a certain depth …, all writings tend to be creative writing, for they all partake of the same essence: poetry. History (contrary to the common view) does not record events. It merely records echoes of events—which is a very different thing—and, in doing this, it must rely on imagination as much as on memory. Memory by itself can only accumulate data, pointlessly and meaninglessly….” ("Lies that Tell the Truth," The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays. New York Review Books, Kindle Edition, 43.) Imagining Mat Scales Here's a tentative imaginative reconstruction involving Matt Scales, one of Tuttle’s defenders. In the last post, I mentioned P. T. Lehman, a Republican activist and minor officeholder in Winston-Salem; he was a justice of the peace. In the campaign of 1898, he played a prominent local part in an insurgency within the Republican Party that offered its own slate of biracial candidates. One of the ringleaders was the Rev. Jethro T. Gibbons, an immigrant to the US from the West Indies and a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Shortly after arriving in Winston-Salem, Gibbons started a newspaper, The Twin-City Herald, apparently for the sole purpose of intervening in the 1898 campaign. (So far as I know, no copies survive.) The paper surprised and dismayed Republicans by attacking them rather than Democrats. At the time it was suspected that his activities were funded by Democrats. (See the Union Republican, 24 March 1898, 2. Bertha Hampton Miller shares this suspicion in her 1981 dissertation, Blacks in Winston-Salem, North Carolina 1895 – 1920.) The alliance with Lehman may support the suspicion. Just two years later Lehman was willing to openly betray his party by supporting the Democrats’ project to disenfranchise more than half its voters; perhaps in 1898 he was prepared to do so surreptitiously by tactics calculated to weaken and divide Republicans. This is only a guess, of course, but it seems at least possible. Now we come to the part played by Mat Scales. Scales was an African American reasonably well known in the white community with a reputation for fighting. For his role in defending Tuttle, Scales was found guilty but received no punishment: he was “discharged without payment of costs” (“The Rioters Sentenced,” Western Sentinel, 29 Aug 1895, 1). We don’t know Scales’ role in the defense of Tuttle, nor the reason for the disposition of his case. In 1897 occurred an incident that throws light on Scales’ character. In the summer, many Winston-Salem citizens traveled by train to nearby towns in brief holiday excursions. On Monday, August 2, an excursion organized by three Black Sunday Schools was returning from Reidsville, a popular destination. Two men on the train began fighting, and when one pulled a knife and began to attack, Scales recruited two other men to help him stop the fight, take the knife, and “arrest” the attacker; on return to town, he was handed over to the police and jailed. Both local papers covered the incident; the facts reported were similar, but The Western Sentinel’s article was sneering in tone and racist in language, even though Scales’ quick action prevented serious injury and possibly murder, and for no obvious gain. I think the character of Scales may be captured in the paper’s intended insult, that he “deputized himself to arrest” the attacker ("Row on the Excursion," 5 Aug 1897, 3). Protecting this victim is consistent with Scales’ joining in the effort to defend Arthur Tuttle from lynching. To purport to understand a character based on two incidents and a prejudiced account is tenuous, an imaginative more than an inferential link. I put it down as a working hypothesis. In spring of the following year, Scales and Gibbons had a dramatic encounter. Gibbons had just launched his newspaper, as described above. Its attacks on Republicans aroused indignation in the Union Republican and probably among Republicans in general. In April, Scales met Gibbons in the street and attacked him with a blow to the face. A struggle followed, stopped only when a bystander took Gibbons’ gun. Gibbons suspected that Scales was paid to attack him, but I’m not aware of any evidence one way or the other. Based on the hints we have of Scales’ character, I wonder if he did not act on his own, or required only the barest of hints to act, to defend the community against political betrayal. Not that the violence was warranted or effective. (The political alliance between Lehman and Gibbons may already have existed, since Gibbons requested that the case against him for carrying a concealed weapon be transferred to Justice of the Peace Lehman.) Aftermath--Gibbons In May, shots were fired into Gibbons’ house at night. At the end of the year, he was assigned by his bishop to lead a congregation in Method, near Raleigh, and early the next year he published a bitter attack against Republicans in the state’s most influential white supremacist paper, Josephus Daniels’ News and Observer (“Another Negro Speaks,” 12 January 1899, 5). Aftermath--Mat Scales In late April, the US declared war against Spain, and Scales enlisted in the army, probably not long afterwards; his reasons are not known to us, of course. In 1899, he received a dishonorable discharge for riot and was imprisoned in Fort Leavenworth for two years. Again, we do not know his motives, but we do know the general context. The all-Black NC 3rd Regiment had Black officers, a fact used in the Democrats' 1898 campaign as evidence of “Negro domination” of the government. The soldiers were mistreated by the white communities where they were stationed—in Fort Macon, where a near riot in Morehead City was occasioned by a conflict between the soldiers and white civilians; in Fort Poland, near Knoxville, TN, where the soldiers were rocked and fired at; and in Camp Haskell, near Macon, GA, where four NC soldiers were killed and the perpetrators found innocent. I do not know the circumstances and motivations of Scales’ offense, but perhaps he had reasons enough to justify to himself his actions based on his self-understanding as a defender and protector, thought we cannot rule out the possibility that he acted out of anger and frustration. Imagining the individual This is the third principle: understanding history through imagining the lives that composed it, even though “individual lives … [are] in the end unknowable,” especially when they could not or did not speak for themselves (Clive James, “Lewis Namier,” Cultural Amnesia). Revised 1 October 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed