Peter Owens testifies about his role in the contested election for sheriff in 1888 ("Boyer vs Teague," Union Republican, Thu, 23 Jan 1890, 1). As noted previously, in the year of the 1895 riot, Toliver and Peter Owens had businesses near the corner of Church and 5th Streets. Owens partnered with Dick Walker in the business of serving snacks (1894/1895 directory). Owens lived nearby on 5th Street. Neal lived farther away, on E 7 ½ Street, in the African American neighborhood near the Depot Street school for African American children.

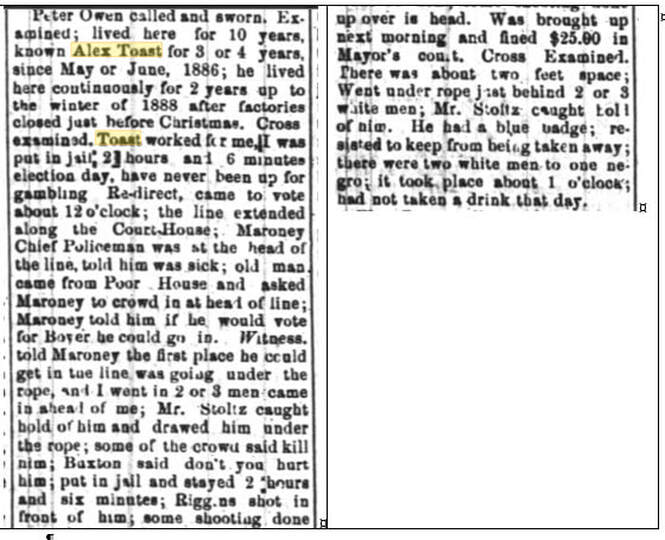

Toliver and especially Owens were acquainted with John Mack Johnson. As noted earlier, Toliver’s sentence to hard time was changed to a stiff fine. Owens pleaded guilty, but judgment was suspended on payment of cost (Union Republican, 22 August 1895). Neal was found not guilty. Like Toliver and Owens, John Mack Johnson pleaded guilty, but he was sentenced to four months hard labor on the county roads (Western Sentinel, 29 Aug 1895). Two years later, he sued unsuccessfully to “recover [$16] stolen [by a guard] while he was on the county roads after the riot” (Western Sentinel, 16 Dec 1897). The profile I am creating suggests that those who acted to protect Arthur Tuttle had attained some success in business, participated in community and political activities, and had an appetite for taking risks. See below for profiles of Peter Owens and John Mack Johnson. The small amount of information I have on W. H. Neal suggests a similar profile; he was a business owner willing to engage in political activity. Peter Owens Owens came to Winston-Salem about 1880, or so he testified in an 1890 electoral fraud case in which Sam Toliver and John Mack Johnson also testified (Union Republican, 23 Jan 1890). The newspaper reports of the trial recount the testimony of both “Peter Owen” and “Peter Owens”—probably a typographical error, but possibly two men in town had similar names. We will encounter this problem with other protectors of Arthur Tuttle. In his testimony at the trial, Owens mentions by the way that he had employed a couple of the contested voters under discussion. Entrepreneurialism is a trait he had in common with Sam Toliver as well as John Mack Johnson. Entrepreneurs are often risk takers; this trait Owens appeared to have in abundance, at least judging from his court appearances. Between 1891 and 1897, Owens (or another man of that name) came before the local courts several times for “retailing”—that is, selling whiskey without a license—and for gambling, twice along with John Mack Johnson (for example, Western Sentinel, 16 May 1895). From what we can tell through the filter of time, Owens seemed to enjoy taking risks. Owens owned some property, a tenement house and lot on Best Street (Union Republican, 14 Nov 1895). Beyond the newspapers, the only records I have been able find concern his marriage to Catherine Miller in 1892. According to the marriage records, he was 64 (born around 1828) and his bride was 36, almost thirty years his junior. If this was the same man arrested after the riot, he was the oldest of Tuttle’s protectors, so far as I have been able to determine from current information. His age may explain why, after he pleaded guilty, his judgment was suspended on payment of cost. In one case, a man found guilty after the riot was released without penalty because of his age; this was George Bailey, possibly born in 1840 (Western Sentinel, 29 Aug 1895; 1900 US Census). But many of those found guilty received minimal or even no penalty, so this is not a strong argument. Some of them were considered old—for example, John Grogan, born in 1836—but some were not. Another trait that Owens shared with Toliver and other Tuttle protectors, including Frank Carter and W.H. (Henry) Neal, was involvement in local politics. In 1892, Owens was on the credentials committee of the county Republican convention, and in 1894 he was named to the state Republican convention (along with lawyer J.S. Fitts and others) by the Wheeler faction of the local Republican party (Western Sentinel, 2 Aug 1894). In his behavior during the much-contested sheriff’s election of 1888, Owens exhibited his risk-taking nature: the details are murky, but it appears he was arrested, apparently for pushing ahead in the voting line, though he said African Americans were outnumbered by whites two to one. After two hours in jail, he was able to vote. Joining the insurgent Wheeler faction took some degree of nerve—splitting the party risked ensuring a Democratic victory, with all the recriminations that such an outcome would entail—as of course did his participation in the assembly to protect Tuttle. John Mack Johnson As already noted, there were several John Johnsons in Winston-Salem in the early 20th century. Ours seems to have appeared in the newspapers as John Mack Johnson, John McJohnson, John Johnson, and perhaps even John Mack. In the 1894-95 directory there were two John Johnson’s in Winston—a tobacco worker who lived at 1012 Oak, and a laborer, at 222 Conrad; and in Salem there was a third, also a laborer, who lived on Salem Hill. I don’t know which, if any of them, was our John Mack Johnson. The man on Oak St lived near one of Arthur Tuttle’s protectors, Oscar Taylor, at 1005 Oak. From the sparse available evidence, John Mack Johnson appears to have been an intimate of Peter Owens and acquaintance of Sam Toliver. All were entrepreneurial. Johnson ran a bar room at times and occasionally organized excursions by train, at least one, to Danville, in partnership with Toliver (Western Sentinel, 2 Jun 1898). Owen and Toliver, as we have seen, both ran eating houses. Owen and Johnson gambled. In May 1894, Peter Owens and eight others, including John Mack Johnson, were charged with gambling; Owens was acquitted, Johnson found guilty (Union Republican, 31 May 1894). Both were arrested on the same charge a year later; Johnson was found guilty, but the newspapers did not report the disposition of Owens’ case (Western Sentinel, 16 May 1895). All three were witnesses in Jan 1890 trial in re fraudulent voting the race for sheriff. A newspaper report of Johnson’s testimony in the trial gives us a rare chance to hear one of Tuttle’s protectors in an approximation of his own voice: "I live on Fifth st., two or three squares from ‘Louse Level;’ I have been keeping barroom; ain’t doing anything now; I have been up before Mayor for gambling twice; submitted both times; been before Mayor four times for fighting…." ( Western Sentinel, 23 Jan 1890). Fighting also indicates a taste for risk, of course, one shared with Johnson by Walter Tuttle and Yancey Simpson (twice found guilty of assault) and others to be discussed later. As I’ve already noted, some of the protectors held minor political offices or party roles, which I take as evidence of bravery or risk tolerance, given the hostility of many whites to African Americans in any political office or role, however lowly. In 1891, John Mack Johnson served on a school committee, along with Charles Tuttle (probably the father of Arthur and Walter (Union Republican, 17 Sep 1891). By 1898, he was taking a more prominent role in politics. He spoke at a Republican county convention in favor of “the contesting delegation” seeking more political representation in the party for African Americans. Perhaps he shared the sentiments of J. M. Hawkins, who gave “a hot speech in favor of the contesting delegates. He said the negro had been treated as a fool and tool long enough” (Union Republican, 2 Jun 1898; Western Sentinel, 2 Jun 1898). Finally, for a time at least, Johnson owned a horse, a fact we know because, in 1893 he threatened to sue the county “for injuries sustained by his horse falling through a bridge on the East Salem Road” (Western Sentinel, 9 Feb 1893). Owning a horse was not common among working class citizens of either race and suggests a degree of prosperity. W. H. Neal Neal is included here because he spoke against the “contesting delegation” in the May 1898 convention mentioned above, where John Mack Johnson spoke. Neal accused one of the speakers of "receiving money for his opposition work to the ‘bosses,’” i.e., chairman Reynolds and other leaders (Union Republican, 2 Jun 1898; Western Sentinel, 2 Jun 1898). This payment may have come from Democrats, as I will discuss in a later post). In an October 1898 political meeting, Neal was quoted by the Winston Salem Journal as making inflammatory comments—"the issue now was the ‘negro man the white woman’” (Winston-Salem Journal, 7 Oct 1898). This comment was quoted by the white supremacist newspaper to inflame whites against the Republican Party. The context of Neal’s comments are not provided, indications of the bad faith characteristic of the Democratic Party. In Sept 1898, W. H. Neal was a businessman who “conduct[ed] a [grocery] store [on E 7 ½ St], east of the … Graded School” for African Americans on Depot Street (Western Sentinel, 8 Sept 1898; Western Sentinel, 28 Apr 1897). I believe him to be the Henry Neal who was found not guilty for charges arising from the “riot.” He was married and had four children (1900 US Census). Like Owens, he was a property owner; in the 1900 census, he owned his home outright.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed