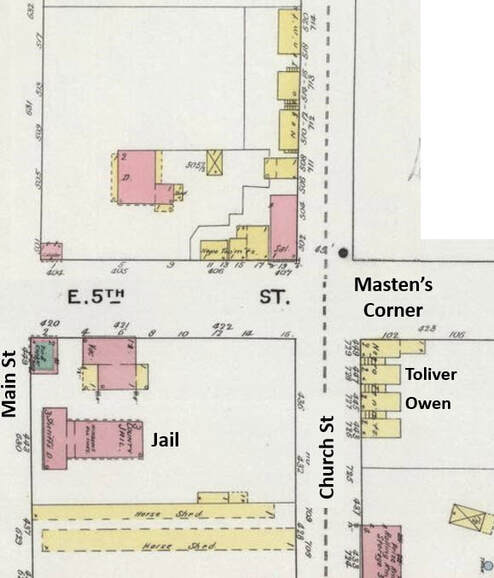

In 1895, Samuel Toliver's shop and home were near Masten's Corner, where the men gathered to protect Arthur Tuttle from lynching, and directly across Church Street from the jail, technically located on Main Street. A neighboring shop was owned by Peter Owen, also arrested for unlawful assembly. Samuel Toliver (FamilySearch personal ID LDPW-D3V) was born in Virginia, probably in or near Richmond, sometime between 1846 and 1852 (the sources differ). In the 1870 census, he may well be the young housekeeper of that name who worked in a hotel in Lexington, Virginia. In 1874, as Samuel Taliaferro, he married his first wife in Richmond. He was probably living there: his mother lived in Richmond at the time of his second marriage in 1885, and as we will see he had important personal and business connections in Richmond.

Toliver came to Winston-Salem in 1882, as he testified in 1890 (Western Sentinel, 23 Jan 1890). Three years later, he married Lizzie Morehead in a ceremony conducted by the locally prominent Baptist minister, G. W. Holland. Toliver had deep connections in the local African American community and was well respected in the white community. The latter fact probably accounts for his presence in the local newspapers. He was an acquaintance and agent for John Mitchell, Jr., the owner and editor of the influential African American newspaper, the Richmond (VA) Planet, and for that reason, if no other, he was occasionally mentioned by that paper, too. By 1889/1890, Toliver owned a grocery store and lived at 447 Church Street in Winston. He was still here at the time of the action to protect Arthur Tuttle. Toliver’s store was near the corner of Church and 5th Street, a location known as Masten’s Corner (see the map above). On the night of August 11, 1895, men gathered at this corner before walking to the nearby jail to protect Arthur Tuttle from the rumored lynching. Toliver was not mentioned in the newspapers as a leader, but his original sentence—four months of hard labor on the county roads—suggests that he was seen as one. His sentence was among the harshest handed down: three men received twelve-month sentences, one man identified as a ringleader received a six-month sentence, and four others, in addition to Toliver, received four-month sentences. The judge reduced Toliver’s sentence to $100 and cost, then a substantial amount of money. The newspapers do not provide a reason for the change, but perhaps we will find it in the judge’s reason for reducing Frank Carter’s sentence: he “had been given an unusually good character and through deference to this [the judge] imposed a fine … instead of consigning him to the county road” (Western Sentinel, 29 Aug 1895). A number of Tuttle’s protectors lived or ran businesses near Toliver, including Peter Owen, a business colleague and probably friend whose snack-bar had been next door, at 445 Church Street, since at least 1889/1890. Owen and another protector, tobacco worker Walter Searcy, lived around the corner on East 5th. In 1890, John Johnson, a tobacco worker and sometime barkeeper, also lived nearby on 5th. Separate articles will consider these relationships in more detail. For now, I will continue with my profile of Toliver. In 1895 and 1897, Toliver was an officer in the Twin City Pythias Lodge, a fact we know from the Richmond Planet (for example, 20 July 1895), not the local papers. (For a brief excursus on social organizations in Winston-Salem, see below.) By 1897, Toliver was the Winston-Salem agent for the Richmond Planet (Richmond Planet, 21 Aug 1897) and occasionally made trips to Richmond to confer with the paper’s owner / editor, John Mitchell, Jr. He was also the Winston-Salem manager of the Working Men's Aid and Beneficial Association in Richmond, VA (Richmond Planet, 29 May 1897). In April 1898, Toliver chaired a ward meeting of the local Republican party (Western Sentinel, 14 Apr 1898). At least one later post will address local politics in detail. In January 1903, a false accusation against Toliver gave a newspaper the occasion to praise him as a “reputable and well known colored business man”: his business was now on Fourth Street (where it had been since at least 1897), and according to the paper “he has a good many friends among the white people of that vicinity” (Winston-Salem Journal, 10 Jan 1903). His health was declining, and he died later that year while seeking medical care in Greensboro (Union Republican, 20 Aug 1903). Excursus—Social Organizations Membership information in the many social and fraternal organization would be very helpful in defining social connections and networks, but unfortunately the local papers showed little interest in such features of the African American community. Even the city directory for the period often ignored these organizations. It would also be helpful to know more about the membership services and benefits provided by the Masons and Odd Fellows, the Knights of Pythias, the Knights of Honor, and other groups, to know more about the cornet and string bands, and to know if there were temperance and literary societies in the community. In the African American cemetery established by the Odd Fellows are buried four men who may have been among Tuttle’s protectors—James Dandridge, Coy Ross, Green Scales, and Sam Snow. Probably many of Tuttle’s protectors had such connections, but they are at present beyond reach. Here's the beginning of an inventory and chronology of such groups and related organizations: 1860s - 1880s

1882

1889

1891/1892

1892-1893

1895

1897

1902/1903

Benevolent associations

0 Comments

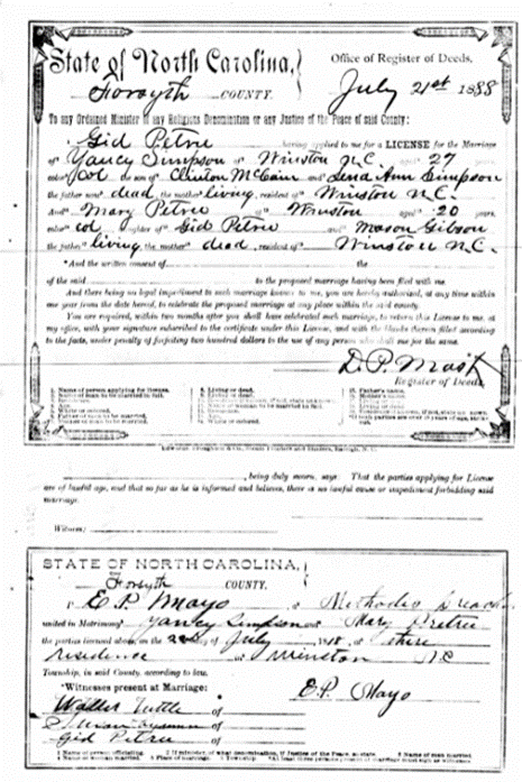

Marriage certificate of Yancey Simpson and Mary Petrie, married 21 July 1888 by the Rev. E. P. Mayo. Witnesses were Walter Tuttle, Susan Bynum (soon to be Walter’s wife), and Gid Petrie, father of Mary and of Ellis Matthews. Up to 300 participated in the effort to protect Arthur Tuttle; we know the names only of those men who were arrested, plus Arthur Tuttle’s sister (no women were arrested). Though those men are hardly a random sample of the participants, I am hoping that studying them will provide insight into their personal connections and social networks, in some cases their political and religious affiliations and their visibility to the white community. The primary motivation to participate must have been protecting a member of the community from torture and murder, but the situation threatened the entire community. In these networks and connections we may perhaps see evidence of the community at work.

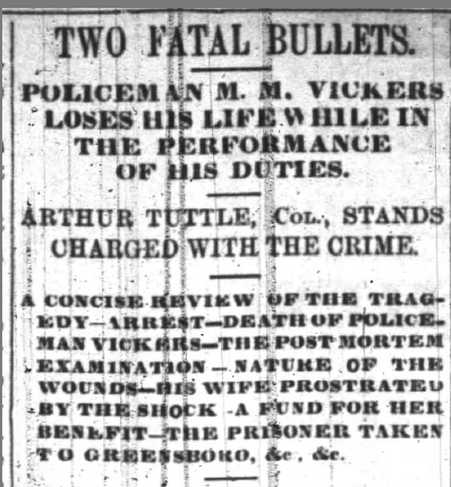

In her dissertation, Miller suggests several reasons for the timing of the riot. First, the Black community had unrealized expectations of political participation and of patronage proportional to the size of their contribution to Republican electoral success. Second, the lynching of five men in Alabama in April had set the African American community in NC on edge; Miller’s evidence is an article in the AMEZ Star of Zion published in Charlotte and a resolution passed in June at an indignation meeting in Winfall, NC. In this tense context, Arthur Tuttle killed Michael Vickers, and the rumors of a lynching immediately spread through Winston-Salem (35-41). Aside from the accounts of the killing of Officer Vickers and the murder trial, the newspapers have little information about Arthur Tuttle’s connections and social networks. To place him in a social context, his older brother, Walter, provides a good starting point. It is likely that Arthur knew many if not all of Walter’s connections, though that is only a surmise. Walter Tuttle and Yance Simpson One of the men arrested in the aftermath of the 1895 riot was Yance or Yancey Simpson (1861/1862 – 1930). He seems to have been a close associate of Walter. When he married Mary Petrie in July 1888, the witnesses included Walter Tuttle and Susan Bynum. When Walter and Susan were married the following month, witnesses included Simpson and his new bride. The Rev. Elijah P. Mayo of the American Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) Church officiated at both weddings. He appears to have left Winston-Salem before the riot. He was appointed to a congregation in Hickory at the end of that year (Press and Carolinian, 12 Dec 1895), but had disappeared from the Winston-Salem newspapers two years earlier. He may have been a significant influence, however. Before his departure, he was politically active. In 1892 he was particularly outspoken in meetings of the Republican Party. Later posts will take up the political situation. The year after their marriages, Tuttle and Simpson were neighbors on Mack Town Street. In 1891, Tuttle and Simpson were still neighbors, now on Blum Row. In December they were both arrested and fined $7; the newspaper did not report the charge (Western Sentinel, 10 Dec 1891). Simpson and Tuttle had fewer documented interactions from 1892 to Tuttle’s death in 1894. As I described in an earlier post, Tuttle became increasingly violent and developed a bad reputation. Simpson may have joined Arthur Tuttle’s protectors because he knew Arthur, or perhaps because of his close association with Arthur’s slain brother, Walter. Yance Simpson and Ellis Matthews Yance Simpson’s wife, Mary Petrie, was the daughter of Gid Petrie (a witness at Yance’s wedding) and half-sister of Ellis Matthews, a son of Gid Petrie and one of the men arrested after the riot. Yance Simpson and Henry Foster In 1894/95, a man named Henry Foster (1355 N Main) lived near Yance Simpson (1366 N Main) and worked as a driver. This may well be the man of that name arrested after the riot. Yance Simpson and Green Scales Another man arrested after the riot was Green Scales. There appear to have been three men with that name in Winston-Salem, the first born in 1838 (died 1924, buried in the Odd Fellows’ cemetery), the next born 1845-1850, and the youngest born 1867/1868. Yance Simpson knew at least one of them. In the 1880 census, the youngest Green Scales was working in a tobacco factory and boarding nearby at 198 Chestnut. Other boarders included Yancey Simpson, then 19 years old. Yancey’s and Green’s boarding together suggests, if only weakly, that this was the man of that name who participated in the riot. Like Simpson and Walter Tuttle, this Green Scales was married in July 1888, but by a justice of the peace and with no overlap in witnesses with the marriages of Simpson and Walter Tuttle. (Surprisingly, perhaps, one of the witnesses was J. W. Bradford, then serving as deputy sheriff and jailer; he became Winston’s Chief of Police a few years later.) In the 1891 city directory, one Green Scales owned a grocery at 1105 Old Town. By 1895, a Green Scales still lived at that address, while presumably another Green Scales lived and ran a restaurant at 205 E. Fifth Street. I do not know the connection between these men. They may have been the same man; people who moved in the course of the year could be listed in the directory at both addresses. In the winter of 1882, Green Scale’s “string band serenaded at several places in town on Monday night” (People's Press, 9 Feb 1882). The restaurant owner lived and worked quite near three other men arrested after the 1895 riot—Peter Owens, who lived a few doors down at 122 E. Fifth, and Walter Searcy, a tobacco worker who lived at 120 E. Fifth. Owens was also a restaurant owner; his restaurant was located just around the corner, at 445 Church St, next door to the restaurant of another arrested man, Sam Toliver, at 447. Summary Familial connections and neighborhood proximity suggest that overlapping social networks of men participating the effort to protect Arthur Tuttle from the lynch mob. As we proceed, we will find more connections, and we will find men who, given the available evidence, cannot be placed in networks—indeed, who cannot be placed in the community beyond the fact of their arrest. The men in the group described here worked as laborers. Like Walter Tuttle, in 1880 Yancey Simpson worked in a tobacco factory, as did the young Green Scales who lived in the same boarding house. Ellis Matthews’ work is not listed in the 1894/95 city directory, but most of his neighbors in Blumtown were laborers. Henry Foster worked as a driver. By 1895, a man or men named Green Scales owned a restaurant and had been a grocer. Next post: Sam Toliver, Peter Owens, John Mack Johnson (or John McJohnson), and Henry Neal. Send comments and questions to [email protected].  The Union Republican (23 May 1895) In 1880, Charles Tuttle (born around 1827) and his wife, Margaret (born around 1841), lived in Middle Fork Township in Forsyth County, a key part of the Black-majority Winston third ward from 1892 to 1895. Charles farmed (the 1900 census shows he owned the mortgaged farm), his wife kept house, and by 1880 some of the children were already working in factories, including Walter at the age of 12. Evidence gathered by Bertha Hampton Miller for her 1981 dissertation suggests that Charles Tuttle “had money and large land holdings which incited envy among many whites”; newspapers from the white and African American communities agreed that the Tuttle sons had “’unsavory reputations’” (“Blacks in Winston-Salem 1895-1920,” 46).

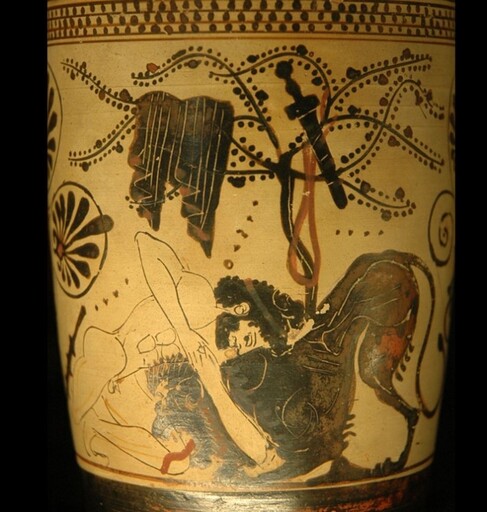

Five of their ten known children figure in the story—Ida, born in 1863; William, born in 1867; Walter, 1868; Robert, 1871; and Arthur, 1875. Until May 1895, Walter was the family member most often in the news. He was frequently in trouble with law, primarily for brawling (the actual charge was “affray”) and assault. So far as can be determined from the surviving newspapers, Walter reached a turning point in his life in March 1892. A drunk white man paid Walter, also drunk, and Sim Brannon to attack a young tobacco farmer from Rockingham County. The attack took place in the Piedmont Tobacco Warehouse. Farmer Nelson gave better than he got: he seriously wounded Walter with a knife and escaped without serious injury, as did Brannon. Chief of Police J. W. Bradford and Brannon sat up all night nursing Walter’s wounds. Tuttle was sent home to recover; before his trial he left town and went into hiding. He was not caught until December 1892. In March 1893 he was convicted on several counts of assault and sentenced to 12 months of hard labor on the county roads. He then disappeared from the Winston-Salem newspapers for about 14 months. In May 1894, Tuttle was arrested for assaulting Bradford, now the former chief, “probably on account of some old grudge because of Bradford’s course in some way against Tuttle during Bradford’s term of office as chief-of-police” (Western Sentinel, 26 July 1894). Possibly Bradford’s treatment of Tuttle for his knife wounds was not as benign as the newspapers reported. Even among his fellow officers, Bradford seems to have had a reputation for harsh treatment; a few years later, when the ex-chief was himself arrested, he accused the arresting officers of mistreatment. One replied, “D--- you, you have treated many a man worse than this for less offences” (Western Sentinel, 9 Dec 1897). Whatever the reason for his assault, Tuttle was convicted. Desperate to avoid another stint at hard labor—aside from the rigors of the prison life, he had a wife and two-year-old daughter—he asked Policeman J. R. Hasten to accompany him to find someone to pay the fine on his behalf. According to Hasten, when they were on the grounds of a tobacco factory, Tuttle tried “to snatch the pistol from [the officer’s] hip pocket, … and … failing in this grabbed” the officer’s billy club (Western Sentinel, 9 Dec 1897). The officer said he pulled his .38 and mortally wounded Tuttle. Eventually, witnesses came forward claiming that the officer had lied, that Tuttle had not gone for the his gun. Hasten was indicted for murder—the first indictment against a Winston-Salem police officer for killing an African American—and in May 1895 he was put on trial. But on Saturday, May 19, the white jury found him innocent. In the afternoon after the verdict, the sidewalks around the courthouse were as usual crowded with pedestrians. Among them was Arthur Tuttle, no doubt angry and upset by Hasten’s acquittal. He refused the orders of two policemen, Michael Vickers and Alex Dean, to move from the sidewalk to let others (probably white women) pass and became verbally defiant; he would move when he “damn got ready” (Union Republican, 15 Aug 1895). One of the policemen moved him from the sidewalk—it is not clear how much force was used—and Walter fought back. During the struggle, Tuttle grabbed a pistol (from his pocket or shirt or perhaps from the ground after it fell from his clothing) and twice shot officer Vickers. He was arrested on the spot; Vickers died the next evening. Fearing that a lynching would be attempted, African Americans gathered near the county jail. The authorities quickly moved Arthur Tuttle to Greensboro, then farther away, to Charlotte. He was returned for the trial in August, despite the request of the defense lawyers for change in venue. When the trial was in recess on Sunday, August 11, the white and black communities were swept by rumors of a gathering lynch mob. That evening, after church service, one of the Tuttle sons, Robert, asked a Methodist Episcopal congregation to take up weapons and gather near the church to protect his brother. In her memoir published just three years later, Ida Beard (daughter of a Confederate veteran) reported it as a night of rumor and fear, rumors that came to her from her husband, who worked in the office of a justice of the peace. To her disgust, he had helped in Tuttle’s legal defense and supported the effort to protect him from lynching. I have seen no evidence that Robert joined the men guarding Tuttle. The oldest Tuttle son, William, evidently participated and then fled to avoid arrest. He was arrested in Statesville at the end of November, but I have not found stories indicating that he was tried. Years later, eyewitnesses reported in interviews that “Tuttle’s sister, Ida, weighing about three hundred pounds, sat on the courtroom steps brandishing two six gun shooters, and warned whites who had gathered a few yards aways: ‘The first white man comes across her to undo this jail door, I’m gonna kill him’” (Miller, 45). Next posts: I will begin exploring the lives and connections of the men who gathered to protect Tuttle. Sources: In addition to Miller’s Duke University dissertation, I have used contemporary newspapers and Fam Brownlee’s very useful account, ”Murder, Rumors of Murder and Even More Rumors…” For a more detailed account, see Appendix C of my annotated edition of Ida Beard’s memoir, My Own Life. Like what you read? Please buy my books! Send questions and comments to [email protected].  White-ground lekythos, ca. 500-475 BC. Attributed to the Diaphos Painter. Public domain (Wikipedia). José de la Heredia (1842 – 1905) was a French poet who was born in Cuba of a Cuban father and French mother. He was educated in France and settled there with his widowed mother. He is best known for the 118 sonnets in Les Trophées, published in 1893. He belonged to the Parnassian group of poets.

I probably came across Heredia when I was using English prose versions to “translate” poems in the Greek Anthology. I often found his sonnets difficult to follow, but beautiful and intriguing. I also liked the scope of Les Trophées--world history (though from a Western perspective; he wrote in the classic age of western imperialism), and nature poems. There are poems on Greek and Latin antiquity and the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and a short section on the Middle East, the Far East, and the tropics. My attention then as now was devoted to the treatments of Greek and Latin myth and history. The second poem in the collection is “Némée,” referring to a location (Nemea) and the Nemean lion, a beast whose golden hide was impervious to weapons and whose claws could penetrate human armor. Némée Depuis que le Dompteur entra dans la forêt En suivant sur le sol la formidable empreinte, Seul, un rugissement a trahi leur étreinte. Tout s'est tu. Le soleil s'abîme et disparaît. À travers le hallier, la ronce et le guéret, Le pâtre épouvanté qui s'enfuit vers Tirynthe Se tourne, et voit d'un œil élargi par la crainte Surgir au bord des bois le grand fauve en arrêt. Il s'écrie. Il a vu la terreur de Némée Qui sur le ciel sanglant ouvre sa gueule armée, Et la crinière éparse et les sinistres crocs ; Car l'ombre grandissante avec le crépuscule Fait, sous l'horrible peau qui flotte autour d'Hercule, Mêlant l'homme à la bête, un monstrueux héros. Hercules and the Nemean Lion (1st draft) Since the Breaker of Beasts entered the forest tracking the frightening pugmarks in the clay, only a roar has betrayed their fierce embrace. Everything is quiet. The sun dips and sets. Through thicket and bramble, across a clearing, the frightened herdsman, fleeing towards the city, turns. Eyes widened by fear, he sees the beast, stopped beside the woods, rising. He cries out; he sees the terror of the lion whose jaw is gaping open to the sky, with his maw of fearsome teeth, his straggly mane. For shadows that creep from the twilit trees are making, under the hide draping Hercules, a monstrous hero, blending beast with man. Understanding the poem may be difficult for modern readers, because Heredia assumes intimate familiarity with the story. In the third line of the first stanza, for example, he refers to “their embrace” (“leur étreinte”) without providing an antecedent for their—an “oversight” that would probably evoke comments in a contemporary poetry critique group. My title, “Hercules and the Nemean Lion,” gives the modern reader a starting place and an explanation for their. Heredia also feels no need to explain étreinte/embrace, a rather understated way to describe the action to come—the hand-to-paw death battle described in the myth and further discussed below. The beginning of this line had another puzzle for me: “Seul, un rugissement a trahi…. Only a roar [or, one roar] has betrayed….” Some background reading clarified: since Hercules’ weapons were powerless, he used his hands to kill the beast by strangulation. Heredia’s version implies that the lion can manage only a single roar before his breath is cut off. I was also puzzled, briefly, by the switch in tense from past to present perfect (from “entered the forest” to “has betrayed”). I wondered about the point of view implied by the change in tense. The next line is in present tense, as is the following stanza (see the third line), but in the second line of that stanzas we find at last the point of view—“le pâtre/the herdsman.” What the herdsman sees, and what we see, is from a distance—the lion stopped at the age of the woods, mysteriously rising, presumably on his hind legs to grapple with Hercules; the lion’s fear; his fanged jaw opening on the bloody sky; and then the hide draped around Hercules (“floating around” him, in the original), for in the myth Hercules removes the pelt and head with the lion’s claws to use as his armor and helmet. The reader must bring these details to the poem. In the gathering darkness, the herdsman sees a monstrous mingling of man and beast. Heredia’s use of monstreux/monstrous introduces another difference from today’s poetic practice. Monstrous meant, originally, a malformed animal or human, often a creature afflicted with a birth defect. Older museum exhibits used to display canisters filled with alcohol and deformed births labeled “monsters.” Later, the term meant an enormous or prodigious animal portending doom. These meanings are greatly attenuated now, and the attitude towards the abnormal has also changed, so it would be harder to use the term in a poem. The same is true for other terms used by Heredia--formidable, sinistre, and horrible. In general, we would likely use fewer adjectives of any kind. These exhausted terms, as well as Heredia’s assumptions about his readers’ background knowledge of classical myth, are barriers to a contemporary appreciation of his artistry and subtlety. Final notes: (1) I wish my rhymes were fuller and richer (especially mane/man) and followed more closely Heredia’s Petrarchan scheme. (2) I recently learned the term pugmark and used it here, where pawprint would probably be more suitable. (3) The final tercet departs furthest from the original. Speculation: Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde appeared a few years before Les Trophées, making me wonder if the devolution of the doctor into the animal-like Hyde influenced Heredia’s understanding of the monstrous man-beast. Since Heredia’s poems were apparently written long before publication, it may be unlikely on chronological grounds, if no other. Please direct any comments to [email protected]. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed