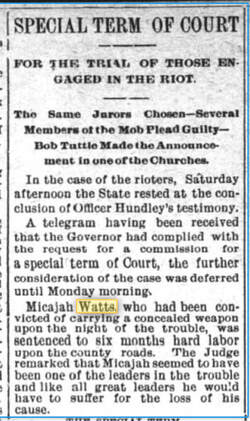

Micajah Watt (or Watts) was identified by the court as a ringleader in the effort to protect Tuttle. Can we find evidence of his leadership outside of the newspapers? (The article excerpt is from the Western Sentinel, 22 August 1895). Connections (3) – Micajah (Cager) Watt and the Depot Street School Neighborhood

Micajah Watt or Watts (1847/1849 – 5 May 1905. PID GS65-YPD). Watt was usually called Cager, but he was also shown in newspapers and elsewhere as Kajah, Cajer, Mc Cager, and possibly Kaziah. At almost 50, Watt was one of the oldest men arrested in the aftermath of the riot; born in 1850 or earlier, he was old enough to remember slavery times. An article in 1886 listed him as one of 68 African Americans in Winston-Salem who owned improved real estate (Western Sentinel, 11 March 1886). The judge at the trial of the rioters considered him a ringleader in the effort to protect Arthur Tuttle. As a ringleader, Watt received a sentence of six months of hard labor on the county road. This was the second most severe sentence handed down. It is possible that his sentence was no longer because of his age; in other cases, as I have noted, the court showed leniency on account of health or age. One of the three men who received longer sentences, Pleas Webster, was a much younger man, somewhere between 27 and 31 years of age, but I have not found evidence for the age of the two other men (Charles Hauser and Frank Robinson) who received a one-year sentence. As a reputed leader, Watt was also singled out for unofficial punishment—abuse while in prison. Although a cook and restaurant owner, he was made to work at hard labor rather than serve as the prison camp’s cook. He was whipped in the camp with the knowledge of, if not at the order of, the camp superintendent. We know this because of a short article on the front page of the Western Sentinel. It begins with a headline—“County Convict Camp. Micajah Watts Was Not Whipped”—that is not supported by the story: the story does not say that Watt was not whipped, but only that he was not whipped by Superintendent Shutt; in recent political jargon, it is a nondenial denial. Beating Watt was obviously meant to intimidate and bully him; placing the story on the first page and printing a denial that, in effect, acknowledged the beating were both consistent with a strategy of intimidating the community that looked up to Watt. But this is admittedly speculation. *********** My original goal in studying the protectors as a group was to ascertain whether Watt was, as claimed by the court and newspapers, a leader in the effort to protect Tuttle. Are there clues that justify the claims that he was a leader in the community? I thought I might find clues in identifying the men who lived near him. Cager Watt lived at 809 Depot St and ran a restaurant at 807 ½ Depot; the “Graded School” for African American children was not far away, at 615 Depot. The Depot Street school was a major institution in the African American community. Established in 1887, its principal from 1890 - 1895 was Simon G. Atkins; in 1895 he moved to take charge of the Slater Institute, forerunner of Winston-Salem State University, where he served for many years. In addition to the men arrested for riot (see below), many prominent citizens lived nearby, including Rufus Clement (801 Depot), an alderman and a member of the Republican Executive Committee; lawyer John S. Fitts (corner of Chestnut and E. 7th), who defended a number of the men arrested for riot; Dr. H. H. Hall, who lived at 127 E. 7th ; and Dr. J. W. Jones, at 710 Chestnut. Nearby institutions included the African American Hook and Ladder company commanded by Aaron Moore (E. 7th near Depot), who served at least one term as alderman. Just across the street from the graded school, on the corner of 7th, was the AME Zion church. If you walked from the corner heading west on 7th, on the right was the Hotel Bethel, the only hotel for African Americans in Winston-Salem. (Later, an important community center, the hall of the Knights of Pythias, was located here.) Just before the hotel, you could turn north on Chestnut and soon walk to the home of the Rev. J. C. Alston at 714, then to his church, Lloyd Presbyterian. Dr. J. W. Jones lived at 710, and few years later, the lawyer James S. Lanier would live at 713, near the Presbyterian church where he worshiped; like Fitts, he defended in court a number of those arrested for riot, including Pleas Webster. Webster lived nearby, at 715 E. 9th. Continuing on 7th, just past the hotel you could turn left on Chestnut and walk south a block to the First Baptist Church, near the corner of 6th Street; the pastor, the Rev. G. W Holland, lived at 309 E. 8th, within easy walking distance and a few doors down from shoemaker Wesley Mitchell, one of Tuttle’s protectors. Holland officiated at the weddings of Samuel Toliver, Walter Price, and Aaron Stone. From the hotel you could also continue west on 7th Street and soon reach, on the left, St Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church and the home of its minister, the Rev. W. W. Pope. Pope officiated at the marriage of Frank Meadows and Sam Penn. His church is likely where Robert Tuttle rose after the service on the evening of August 11, 1895, to ask the congregation to gather near the jail to protect his brother, Arthur, from lynching. *********** Given the vibrancy of the neighborhood, it is not surprising that many of its citizens would have acted to protect Tuttle. The information available cannot prove that Watt was a leader. But it is still interesting and possibly significant that between Watt’s business and the Depot St. school lived several men arrested for participation in the riot: William Cooper (724 ½ Depot St)—sentenced to pay proportion of costs. He may also have been known as Will Copper, and there may have been a white man in town with the same name. I have not found other connections for him. Calvin Martin (738 Depot)—indicted, but no information available on the disposition of case. Two men named Calvin Martin seemed to have lived in town at the time, close in age, but married to different women. The Martin on Depot St (born 1864 – 1869) married Mary Davis in 1891; the other (born 1872) married Paulina Mitchel in 1895. Both marriages persisted into the next century. Both men were working class. I don’t know which man was involved in the riot, but I suspect it was the older man. Matt Malone (728 ½ Depot)—discharged without payment of costs. Another Matt Malone—or perhaps the same man who moved while the 1894 directory was being prepared—lived nearby, at 330A 7½ St., the same address as Walter Price, found not guilty. I have not established other connections for Malone. Price was married in September 1894 by the Rev. G. W. Holland to Alice Holmes of Reidsville; I have found no other connections for him. Henry (W. H.) Neal’s home and grocery store were near Price, at 313 7½ St; he was found not guilty. He was politically active a few years later, in the hotly contested election of 1898. On one occasion, he and John Mack Johnson appeared to take the opposite sides in an acrimonious debate; in a later discussion, his words were construed (or misconstrued) by the local white supremacist newspaper to heighten racial tension. I will discuss politics in more detail later. James Williams (734 ½ Depot)—sentenced to 4 months of hard labor on the county roads. I have not established other connections for Williams. Other rioters who lived nearby on other streets include: Frank Carter (possibly the C. F. Carter who lived at 523 Sycamore St)—pleaded guilty, but because of his high character, was not sentenced to hard labor but fined $50 and his proportion of costs. Carter likely lived near the school, since he was employed there as a janitor—a salaried position that was highly coveted. He was licensed to preach by a local church (I don’t know which) and, like Samuel Toliver and James Dandridge, he belonged to the Knights of Pythias. He also employed tobacco stemmers. I think it quite likely that contemporary sources sometimes identified him by his initials. Most white men and certain African American men, primarily those accorded a degree of respect by the white community, were known in the newspapers by their initials—R. J. Reynolds, for example. African American ministers were regularly identified this way, for example, the Rev. G. W. Holland, minister at the 1st Baptist Church. Usage was not consistent. It is possible but not certain, then, that C. F. Carter was Frank Carter. Also living on Sycamore, at 608 was John Grogan, found guilty but released without fine, costs, or hard labor. Wesley Mitchell (315 E. 8th St)—not guilty. I have not been able to establish other connections for him. Aaron Stone (618 Chestnut St, just south of the Presbyterian minister and his church)—For unknown reasons, his sentence—three months at hard labor on the public roads—was changed by the judge to $50 and cost. I have not been able to establish other connections for him, except the fact the Rev. G. W. Holland officiated at his wedding. James Dandridge also lived on Chestnut St, at 253. He was sentenced to four months at hard labor on the county roads. As I noted in a previous post, there were later at least three men of this name in town. I do not know which of the men lived on Chestnut, nor which participated in protecting Tuttle. The oldest of the three seems to have been about the same age as Cager Watt; at his death in 1922, he was a member of the Masons, the Knights of Pythias (like Samuel Toliver and Frank Carter), and the Odd Fellows, in whose cemetery he was buried. *********** As with my previous posts, this is an interim report. There are a few known sources of inform I have yet to explore and perhaps better ways of assembling and understanding the information I have already gathered.

0 Comments

Prosopography in 1895 Winston-Salem: Difficulties

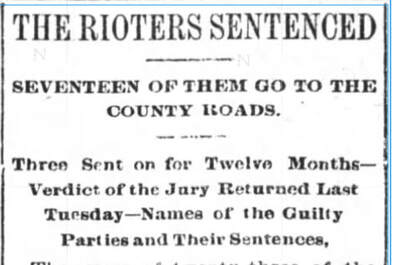

Before going on, it may be useful to note the limitations imposed by the available information: (1) So far as I know, none of the men in included in my collective portrait left their own words behind. With the exception of one or two newspaper articles, we cannot hear them in their own voices, even at second hand. (2) Because of a major fire in the fall of 1892—it destroyed two city blocks, including a bank and several businesses, a factory, and a warehouse—the twin cities and their business leaders became serious about fighting fire. An invaluable resource from our period is the Sanborn-Perris insurance maps published in April 1895. But they focus on the areas of the city where there was heavy capital investment in factories and institutions; outlying areas are not included, and minor streets are not named. Many of Arthur Tuttle’s protectors lived in areas not covered by the map. (3) We know where many of the protectors were living in 1894 because of the directory for the cities of Winston and Salem published that year by E. F. Turner of Yonkers, NY. The directory lists name and occupation, home address, and often business address. It also segregates the citizens by race, a practice we avoid in directories (but not the US census), but it is useful for analyzing the racial composition of neighborhoods and occupations. This resource, as useful as it is, also has its limitations. It generally does not list women in households that include a male relative. It may have also excluded some areas dominated by African Americans; this omission, if it occurred, would explain why men known to have lived in the area during this period are not listed in any of the directories (I have reviewed those published in 1884 and 1890, as well as in 1894). Further, the testimony in the 1890 trial of the contested election of 1888 (see previous posts) suggests that African Americans often moved in and out of town, in part I suspect because tobacco factories were not open year-round. Many may have been away when citizens were being identified for the directories. (4) The detailed information from the 1890 US census was destroyed many years ago, leaving a large gap in the available information for our period. (5) Until 1898, no newspapers in Winston-Salem were published by and for African Americans, and no copies of the short-lived Twin-City Herald published in that year are known to exist. Out-of-town papers—notably the Richmond (VA) Planet and the Star of Zion, published in Charlotte—did occasionally cover news from Winston-Salem, including but not limited to the 1895 riot. (6) Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.com have collected marriage records that, where they exist, are useful in showing age, family relationships, and other connections; for example, as I have already discussed, Yance Simpson and Walter Tuttle attended each other’s weddings in the summer of 1888. These information gaps mean that we can gain at best only a limited understanding of the men who were arrested as they attempted to protect Arthur Tuttle.  Headline in the Western Sentinel on 29 August 1895. The newspaper was a proponent of secession before the Civil War, and of white supremacy afterwards. It was disappointed in the court's leniency—that is, some were acquitted, and some found guilty but discharged without punishment, or subjected to fines and court costs in lieu of harsher punishment. But many were sentenced to 3-12 months of hard labor. Overview of Tuttle's Protectors

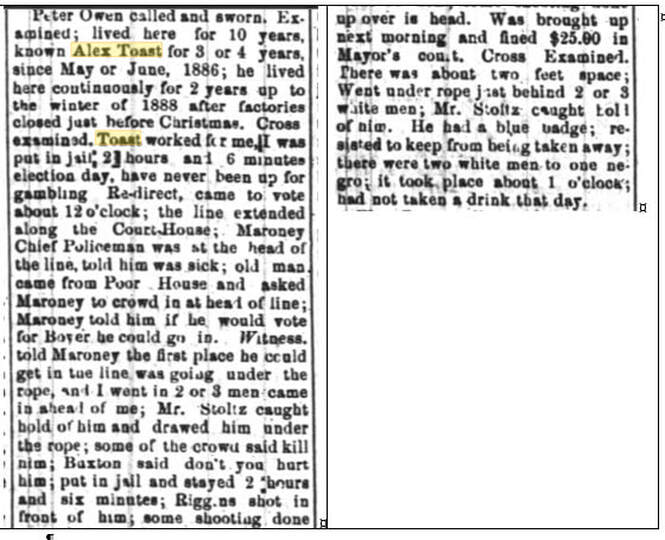

Before going on, it may be helpful to provide an overview of the men who banded together on the night of Sunday, August 11, 1895, to prevent the feared lynching of Arthur Tuttle. I will list the protectors, along with a few others, noting birth and death information, where I have it; known occupation around the time of the riot; and the sentence issued for participating in the riot. The newspapers are not always clear or consistent about the charges, but at least some were charged with carrying concealed weapons or unlawful assembly. In many cases, birth and death dates and locations are tentative. Based on available information, in some cases I’ve noted dates for which there is evidence the men were still alive or no longer alive. NOTE: PID means personal identification number in FamilySearch.org. Tuttle, Arthur (born 1875 in Forsyth Co, NC; died 1946 in Philadelphia, PA. PID G7X2-5M2). I’ve no evidence that he worked tobacco in Winston-Salem, but it’s likely. On moving to Philadelphia after his release from prison, he worked in a cigar factory. Trial: guilty of 2nd degree murder, sentenced to 25 years, with possibility of release in 17-18 years based on good behavior. But he appears to have served no more than 15 years, possibly no more than 8. Tuttle, Walter (1867 – 1894; born and died in Forsyth Co NC. PID G7X2-MD8). Worked as a roller in a tobacco factory. Killed by policeman Hasten in July 1894. Protectors—those discussed in earlier posts 1. Foster, Henry (possibly born 1875 in Davie Co, died 1949). Started as tobacco worker, but by the time of the riot (and later) was working as hostler, driver, and coachman. Trial: acquitted. 2. Johnson, John Mack (John McJohnson) (born unknown, died after 1898). Tobacco roller, once owned a bar and organized an excursion. Trial: pleaded guilty; sentenced to 4 months at hard labor on the county road. 3. Matthews, Ellis (born 1870, died unknown). Occupation not known. Trial: found guilty; discharged upon payment of his proportion of the costs. 4. Neal, W. H. (born 1856 in NC, died probably after 1922). Grocer. Trial: not guilty. 5. Owens, Peter (born 1828?, died 1897 or later). Co-owned restaurant serving snacks. Trial: pleaded guilty; judgment was suspended on payment of cost. 6. Scales, Green (There were three: 1: Born 1838, died 1924, probably in Winston-Salem, since he is buried in Odd Fellows’ cemetery; 2: Born in NC 1845-1850; 3: Born 1867 in NC). A young Green Scales worked tobacco; later, a man or men of that name ran a grocery store and a restaurant. Trial: acquitted. 7. Searcy, Walter (born 1870/1877, possibly died after 1918). Tobacco worker. Trial: acquitted. 8. Simpson, Yancey (born 1861/1862 in NC, died 1930 in Goldsboro, NC). Worked as a tobacco roller. Trial: pleaded guilty; judgment suspended on payment of cost. 9. Toliver, Samuel (last name also spelled Taliaferro and Tolliver) (born 1846/1852, probably in Richmond, VA; died 1903 in Greensboro, NC. PID LDPW-D3V). Owned a restaurant, was agent for the Richmond Planet, represented an insurance company, and at least once organized an excursion. Trial: pleaded guilty. Fined $100 and cost; originally sentenced to four months at hard labor, but the judge softened the sentence. Protectors—to be discussed in detail in later posts 10. Bailey, George (possibly born 1840 in Virginia; death unknown, probably after 1902). Tobacco worker. Trial: because of weak evidence and his age, judgment was suspended. 11. Barnett (or Bennett, Bonnet, or Bornett), Robert (There were 2: older was born 1862, died unknown; younger was born 1882/1883, died 1960, in Winston-Salem, NC). The younger man later worked in tobacco. Trial: payment of proportion of costs. 12. Brim, Joe (born 1864, in VA, possibly Patrick Co; died in Winston-Salem in 1909). Began as laborer, later owned a restaurant and a butcher/oyster shop at City Market. Trial: Not guilty. 13. Carter, Frank (born 1864/1865, possibly in Forsyth Co; died after 1900). Janitor of Depot St School, licensed preacher, town commissioner, employed tobacco stemmers. Trial: pleaded guilty; because of his high character, fined fifty dollars and his proportion of the costs rather than hard labor. 14. Copper, Will or Will Cooper (unknown). Laborer. Trial: Guilty; pay his proportion of the costs. Will Copper and Will Cooper may or not be the same person. 15. Dandridge, James (Jim) (At least 3 men of this name--1: born 1840/1850 in Henry Co, VA, died 1922 in Winston-Salem, buried in Odd Fellows' cemetery; 2: born 1876 in Ohio, died in 1931 in Winston-Salem, buried in Happy Hill Cemetery; 3: Samuel James, born 1880 in Virginia, son of James Dandridge 1; died 1956). The men with this name worked as laborer, tobacco roller, and driver. Trial: four months at hard labor on county roads. 16. Day, Earnest (born 1875/1878, in Florida; died after 1938). Laborer. Trial: Pleaded guilty; sentenced to 4 months at hard labor on county roads. 17. Foster, Della (born 1876 in NC, died after 1923). Occupation in 1894/95 not known; later worked as barber, laborer, factory worker. Trial: Not guilty. 18. Foy, Lee (born 1870 in NC; died possibly after 1924). Shoemaker. Trial: pleaded guilty; sentenced to 3 months of hard labor on the county roads. 19. Goins, Gus (born 1875/1879 in Winston-Salem; died 1951 in Pittsburgh, PA). Laborer. Trial: pleaded guilty; sentenced to 4 months at hard labor on county roads. 20. Grogan, John (born 1836 in Maryland; died after 1906. PID GWJ6-27M). Tobacco worker. Trial: discharged without payment of costs, possibly because of age. 21. Hart, Morgan (born 1864/1865, possibly in Edgecombe, NC; died 1935 in Columbus, OH; PID GQM7-HSC). Tobacco worker. Trial: pleaded guilty; sentenced to 4 months at hard labor on county roads. 22. Hauser, Charles (unknown). Occupation unknown. Trial: 12 months at hard labor on the county roads. 23. Hopkins, Gus (unknown) . Occupation unknown. Trial: arrested and jailed, but possibly released without trial. 24. Jones, Nathan (Nat) (born 1866 in Virginia; died after 1902/1903; PID GWJN-V92). A man of that name was later a laborer. Trial: four months at hard labor on county roads. 25. King, Frank (born 1881, died 1937 in Winston-Salem and buried in Happy Hill). Plasterer. Trial: acquitted. 26. Knowles or Noals, Ed. (Also possibly spelled Noel or Noell) (unknown). Occupation unknown. Trial: acquitted. 27. Lee, Felix (born 1873 in Caswell Co, NC; died 1962 in Lexington, NC. PID GCMY-RR7). So far, no one of that name have been found in Winston-Salem, but this farmer in nearby Davidson County may have been in town to buy and/or sell. Trial: not guilty. 28. Malone, Mat (born 1868/1871 in Warrenton, NC; died before 1940, probably in Winston-Salem). Tobacco worker. Trial: discharged without payment of costs. 29. Martin, Calvin (born 1869/1872 in NC; died unknown). Tobacco worker. Trial: Indicted, but no further info available. 30. Matthews, Soon (unknown) . Occupation unknown. Trial: acquitted. 31. Meadows, Frank (born 1867/1869 in NC, died after 1903). Tobacco worker. Trial: Not guilty, possibly because he identified a number of the defendants. 32. Mitchell, Wesley (unknown). Shoemaker. Trial: Not guilty. 33. Myers, Tom (born 1874, died 1899 in Winston-Salem). Occupation unknown. Trial: 4 months at hard labor on the county roads. 34. Penn, Sam (There were three. 1: born 1862, died unknown; 2: born 1875/1880, died unknown; 3: unknown). Occupation in 1894/1895 unknown. Sam Penn 2 and 3 later worked in tobacco factories. Trial: 3 months at hard labor on the county roads. 35. Price, Walter (born 1871/1873 in NC, died after 1902). Tobacco worker. Trial: Not guilty. 36. Robinson, Frank (born unknown, died after 1916). Laborer. Trial: 12 months at hard labor on the county roads. 37. Ross, Coy (born in Union Co, SC, 1861/1865; died in Winston-Salem in 1936 and buried in Odd Fellows’ cemetery. PID GWJ7-CJ3). Later a tobacco worker, his occupation in 1895 is not known. Trial: Four months at hard labor on the county roads. 38. Scales, Mat (born unknown, died after 1906). Occupation unknown. Trial: guilty; discharged without payment of costs. 39. Skeen or Skeens or Skeenes, Sam (born 1862, probably in Randolph Co, NC; probably died before 1910). Tobacco worker. Trial: guilty; discharged without payment of costs. 40. Smith, Charles (unknown; possibly a schoolboy born 1878, died 1896 in Winston-Salem, and/or a tobacco worker with unknown dates). Trial: not guilty. 41. Snow, Sam (born 1876 in Germanton, NC; died 1953 in Winston-Salem and buried in Odd Fellows’ cemetery). Tobacco worker. Trial: Not guilty. 42. Steele, Anderson (unknown). Plasterer. Trial: guilty, but sentence suspended due to infirmity. 43. Stone, Aaron (born 1864/1865 in NC, died unknown). Tobacco worker. Trial: His sentence—three months at hard labor on the public roads—was changed by the judge to $50 and cost. 44. Taylor, Oscar (born unknown, possibly died after 1931). Tobacco worker. Trial: pleaded guilty; sentenced to four months at hard labor on the county roads. 45. Tuttle, Will (born 1868 in Forsyth Co, NC; died after 1903. PID G7X2-5FM). Occupation unknown. Trial: arrested; disposition of case unknown. 46. Watt, Micajah (born 1847/1849, possibly in Rockingham Co; died 1905, in Manhattan, NY. PID GS65-YPD). Cook, restaurant owner. Trial: pleaded guilty; sentenced to 6 months at hard labor on the county roads. 47. Webster, Pleas (1: born 1864 – unknown; 2: born 1868 - unknown). Probably tobacco worker. Trial: Pleaded guilty; sentenced to 12 months at hard labor on the county roads. 48. Williams, James (Jim) (unknown). Tobacco worker. Trial: four months at the county road. Edited 14 Sept 2022  Peter Owens testifies about his role in the contested election for sheriff in 1888 ("Boyer vs Teague," Union Republican, Thu, 23 Jan 1890, 1). As noted previously, in the year of the 1895 riot, Toliver and Peter Owens had businesses near the corner of Church and 5th Streets. Owens partnered with Dick Walker in the business of serving snacks (1894/1895 directory). Owens lived nearby on 5th Street. Neal lived farther away, on E 7 ½ Street, in the African American neighborhood near the Depot Street school for African American children.

Toliver and especially Owens were acquainted with John Mack Johnson. As noted earlier, Toliver’s sentence to hard time was changed to a stiff fine. Owens pleaded guilty, but judgment was suspended on payment of cost (Union Republican, 22 August 1895). Neal was found not guilty. Like Toliver and Owens, John Mack Johnson pleaded guilty, but he was sentenced to four months hard labor on the county roads (Western Sentinel, 29 Aug 1895). Two years later, he sued unsuccessfully to “recover [$16] stolen [by a guard] while he was on the county roads after the riot” (Western Sentinel, 16 Dec 1897). The profile I am creating suggests that those who acted to protect Arthur Tuttle had attained some success in business, participated in community and political activities, and had an appetite for taking risks. See below for profiles of Peter Owens and John Mack Johnson. The small amount of information I have on W. H. Neal suggests a similar profile; he was a business owner willing to engage in political activity. Peter Owens Owens came to Winston-Salem about 1880, or so he testified in an 1890 electoral fraud case in which Sam Toliver and John Mack Johnson also testified (Union Republican, 23 Jan 1890). The newspaper reports of the trial recount the testimony of both “Peter Owen” and “Peter Owens”—probably a typographical error, but possibly two men in town had similar names. We will encounter this problem with other protectors of Arthur Tuttle. In his testimony at the trial, Owens mentions by the way that he had employed a couple of the contested voters under discussion. Entrepreneurialism is a trait he had in common with Sam Toliver as well as John Mack Johnson. Entrepreneurs are often risk takers; this trait Owens appeared to have in abundance, at least judging from his court appearances. Between 1891 and 1897, Owens (or another man of that name) came before the local courts several times for “retailing”—that is, selling whiskey without a license—and for gambling, twice along with John Mack Johnson (for example, Western Sentinel, 16 May 1895). From what we can tell through the filter of time, Owens seemed to enjoy taking risks. Owens owned some property, a tenement house and lot on Best Street (Union Republican, 14 Nov 1895). Beyond the newspapers, the only records I have been able find concern his marriage to Catherine Miller in 1892. According to the marriage records, he was 64 (born around 1828) and his bride was 36, almost thirty years his junior. If this was the same man arrested after the riot, he was the oldest of Tuttle’s protectors, so far as I have been able to determine from current information. His age may explain why, after he pleaded guilty, his judgment was suspended on payment of cost. In one case, a man found guilty after the riot was released without penalty because of his age; this was George Bailey, possibly born in 1840 (Western Sentinel, 29 Aug 1895; 1900 US Census). But many of those found guilty received minimal or even no penalty, so this is not a strong argument. Some of them were considered old—for example, John Grogan, born in 1836—but some were not. Another trait that Owens shared with Toliver and other Tuttle protectors, including Frank Carter and W.H. (Henry) Neal, was involvement in local politics. In 1892, Owens was on the credentials committee of the county Republican convention, and in 1894 he was named to the state Republican convention (along with lawyer J.S. Fitts and others) by the Wheeler faction of the local Republican party (Western Sentinel, 2 Aug 1894). In his behavior during the much-contested sheriff’s election of 1888, Owens exhibited his risk-taking nature: the details are murky, but it appears he was arrested, apparently for pushing ahead in the voting line, though he said African Americans were outnumbered by whites two to one. After two hours in jail, he was able to vote. Joining the insurgent Wheeler faction took some degree of nerve—splitting the party risked ensuring a Democratic victory, with all the recriminations that such an outcome would entail—as of course did his participation in the assembly to protect Tuttle. John Mack Johnson As already noted, there were several John Johnsons in Winston-Salem in the early 20th century. Ours seems to have appeared in the newspapers as John Mack Johnson, John McJohnson, John Johnson, and perhaps even John Mack. In the 1894-95 directory there were two John Johnson’s in Winston—a tobacco worker who lived at 1012 Oak, and a laborer, at 222 Conrad; and in Salem there was a third, also a laborer, who lived on Salem Hill. I don’t know which, if any of them, was our John Mack Johnson. The man on Oak St lived near one of Arthur Tuttle’s protectors, Oscar Taylor, at 1005 Oak. From the sparse available evidence, John Mack Johnson appears to have been an intimate of Peter Owens and acquaintance of Sam Toliver. All were entrepreneurial. Johnson ran a bar room at times and occasionally organized excursions by train, at least one, to Danville, in partnership with Toliver (Western Sentinel, 2 Jun 1898). Owen and Toliver, as we have seen, both ran eating houses. Owen and Johnson gambled. In May 1894, Peter Owens and eight others, including John Mack Johnson, were charged with gambling; Owens was acquitted, Johnson found guilty (Union Republican, 31 May 1894). Both were arrested on the same charge a year later; Johnson was found guilty, but the newspapers did not report the disposition of Owens’ case (Western Sentinel, 16 May 1895). All three were witnesses in Jan 1890 trial in re fraudulent voting the race for sheriff. A newspaper report of Johnson’s testimony in the trial gives us a rare chance to hear one of Tuttle’s protectors in an approximation of his own voice: "I live on Fifth st., two or three squares from ‘Louse Level;’ I have been keeping barroom; ain’t doing anything now; I have been up before Mayor for gambling twice; submitted both times; been before Mayor four times for fighting…." ( Western Sentinel, 23 Jan 1890). Fighting also indicates a taste for risk, of course, one shared with Johnson by Walter Tuttle and Yancey Simpson (twice found guilty of assault) and others to be discussed later. As I’ve already noted, some of the protectors held minor political offices or party roles, which I take as evidence of bravery or risk tolerance, given the hostility of many whites to African Americans in any political office or role, however lowly. In 1891, John Mack Johnson served on a school committee, along with Charles Tuttle (probably the father of Arthur and Walter (Union Republican, 17 Sep 1891). By 1898, he was taking a more prominent role in politics. He spoke at a Republican county convention in favor of “the contesting delegation” seeking more political representation in the party for African Americans. Perhaps he shared the sentiments of J. M. Hawkins, who gave “a hot speech in favor of the contesting delegates. He said the negro had been treated as a fool and tool long enough” (Union Republican, 2 Jun 1898; Western Sentinel, 2 Jun 1898). Finally, for a time at least, Johnson owned a horse, a fact we know because, in 1893 he threatened to sue the county “for injuries sustained by his horse falling through a bridge on the East Salem Road” (Western Sentinel, 9 Feb 1893). Owning a horse was not common among working class citizens of either race and suggests a degree of prosperity. W. H. Neal Neal is included here because he spoke against the “contesting delegation” in the May 1898 convention mentioned above, where John Mack Johnson spoke. Neal accused one of the speakers of "receiving money for his opposition work to the ‘bosses,’” i.e., chairman Reynolds and other leaders (Union Republican, 2 Jun 1898; Western Sentinel, 2 Jun 1898). This payment may have come from Democrats, as I will discuss in a later post). In an October 1898 political meeting, Neal was quoted by the Winston Salem Journal as making inflammatory comments—"the issue now was the ‘negro man the white woman’” (Winston-Salem Journal, 7 Oct 1898). This comment was quoted by the white supremacist newspaper to inflame whites against the Republican Party. The context of Neal’s comments are not provided, indications of the bad faith characteristic of the Democratic Party. In Sept 1898, W. H. Neal was a businessman who “conduct[ed] a [grocery] store [on E 7 ½ St], east of the … Graded School” for African Americans on Depot Street (Western Sentinel, 8 Sept 1898; Western Sentinel, 28 Apr 1897). I believe him to be the Henry Neal who was found not guilty for charges arising from the “riot.” He was married and had four children (1900 US Census). Like Owens, he was a property owner; in the 1900 census, he owned his home outright. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed