Der Zufall ist Gottes Art anonym zu bleiben.

Coincidences are God’s way of remaining anonymous.—Albert Einstein

Coincidences are God’s way of remaining anonymous.—Albert Einstein

Part 5: Daddy Becomes Vice President, with a Digression on Timelines [Draft 2]

I first saw this headline and story in the microfilm room of the Forsyth County Library more than 20 years ago. Seeing my father's name came as a shock and revelation. (See more below.)

I don't know exactly when Daddy started his work at the bank, but we moved to North Wilkesboro on a cold, wet day when I was in the seventh grade. My mother remembers the date, February 1, 1965, and that it was snowing. I was cold—the house was poorly insulated, the door was open for the movers—so Mom and I sat together on the floor and covered up with furniture pads, my second fond memory of the pads. I recall feeling particularly close to her that day, perhaps because I had her to myself—the other children were elsewhere, but I don't know where. By now, the family was complete. My youngest brother had been born a few months before, in August 1964. We were still living in Wytheville, Virginia, then; I remember because, when Mom was in the hospital for the delivery, the plaster on the living room ceiling fell on the couch and coffee table. It happened in the middle of night and woke us with a house-shaking crash. The baby was delivered in the little rural hospital in Jefferson. We had not long left our home near Jefferson, so when Daddy and I went to the hospital, we stopped by the old place and ate some Big Boy tomatoes from the vines we’d planted in the spring.

At first we lived in the cold house at the top of Ninth Street hill, across a side street from the fire department. Every day, the alarm at the fire station signaled the noon hour with a blast of sound that could be heard over much of the town. If I was in the yard, it often made me jump. When a fire was reported, the alarm blasted a code indicating the general location of the fire.

Although I had the best room in the house, with a row of three windows overlooking the yard, I didn't like the house or living in town. Then we moved about ten miles north, to a farmhouse on highway 18. The view was not as interesting as it had been in Jefferson—there was no beautiful mountain looming over the place—but the farmhouse was also set in fields near a large expanse of woods, with a fine old barn and several outbuildings. The kitchen and a nearby outbuilding were connected by a covered breezeway where we sat to hull beans, shuck and silk corn, and slice peaches for canning. It was the best feature of the house, at least in memory.

Not far from the house was a deep gouge in the earth said to have been formed by the flood of 1916, and on a hill nearby was the grave of a distant ancestor, Abraham Absher. It was a place wonderfully suited for our night games of hide and seek. We were living here, on the old Hayes place, when baby brother contracted pneumonia and almost died. While Mom and Daddy spent hours by the hospital bed, our great aunt Maude came to look after us and milk the cow.

Then Daddy bought an old farmhouse, about ten miles south of North Wilkesboro on highway 115, also set in fields near a large woodland. The house had been built by the farmer from whose widow we bought the place. Daddy claimed there wasn’t a plumb corner in the house. It was the first place we had owned since his nervous breakdown in Marion, Virginia, about ten years before. This is the farm mentioned in Part 4 where we often encountered copperheads and rattlesnakes. Daddy had a den and bathroom added to the back of the house before we moved in, and we painted the exterior with a glossy dark brown that was, I think, much more chocolate in color than my parents anticipated; in a certain light, it reflected the trees and bushes around it and turned a muddy green. There was no air conditioning, but at the top of the stairs, over the landing, was a large ceiling fan that sucked in the cooler night air through our open windows and across our sleeping bodies. We were living here when I graduated high school in 1970, attended my first year at BYU, and left for my mission in 1971. Here we were living when Daddy’s life began falling apart, though for a long time it was not visible to me.

An incident occurred here that has stayed with me for a long time because of its suggestive relationship with what followed. In my journal I wrote years afterward:

“From an undated piece of paper inserted in my journal; it was probably written around the time I had lived longer than [Daddy, that is, around 2002, and certainly before my sister's revelations to me in early 2006]:

“‘When I was in high school, I wrote some fantasy about committing suicide. I don’t remember anything about the contents, except a vague recollection of some sort of parade that somehow illustrated my character flaws, as I saw them, and moments of humiliation; it was written, I think, in red ink. Mama or Daddy found this story [in my bedroom] and were genuinely concerned. Daddy asked me to promise that I would never kill myself. I promised, and though I did not have time to consider it (he had caught me off-guard), my promise was completely serious. When I was depressed for all those years, though I was not consciously considering suicide (Martha [my wife at the time] thought I was, she told me later, and felt trapped by it), the memory of that promise was something that gave me a glimmer of hope, for I knew that I would never bottom out into self-annihilation. I knew I would keep the promise.’

“Until last night, I’d never realized the irony of this episode. I started to feel again the anger I’ve been feeling lately—not overwhelming or ruinous as it felt years ago, but peeking out at unexpected times. Very unpleasant. Today I realized that I’d never let myself feel anger at Daddy for abandoning us, for leaving Mom with so few assets, and all of us (I'm sure) with unsettled issues. Perhaps I was angriest because he had acted so stupidly, as if he had no other choices. Because he gave up on his early dreams so damned easily. Because he faced a horrible challenge and did not triumph. Because I’ve outlived him in years and yet feel, with all his faults, that I’m not half the man he was. Because [my son] John couldn’t know him (the hardest thing of all).”

Years later I wrote a poem about the incident:

He Came to Me

He came to me. Evening was in the sky,

pinking the east, graying the west, the wave

of darkness rising. We didn’t mean to pry.

Your mama found this in your room and gave

this poem to me. (He held my fantasy

about suicide.) Son, will you swear

never to do this to us? When he sweetly

took my hand—the left—I was half-scared,

but gave my covenant. And I have kept it,

though he broke faith, slipping down a hole

in the world that nearly pulled me through.

The breach is plugged for now with blood and spit.

Sometimes it leaks radiance, a dark blue.

I will go there when I can go whole.

(Visions International, 2009)

But, to return to our narrative, when Daddy first joined the bank, he was involved in selling repossessed equipment and vehicles. I don’t know his title then, but soon he became a vice president. The bank had many of them. Above them were senior vice presidents; Booner had become a VP in 1958, then senior VP in 1964. There were also executive vice presidents; so far as I can tell from contemporary newspaper articles, most of the executive VPs had overall responsibility for the bank’s operations in a town or city. But there was at least one exception: at some point (I don’t know when), Daddy was promoted to be executive vice president of Consumer Relations.

Though I did not know this until many years after his death, Daddy also had a position in another company, Certified Check and Title. I remember a few occasions when he would get on the phone and make long-distance calls to potential sellers and buyers of heavy equipment. I assumed this was his own side business, but testimony and news stories in 1976 and 1977 suggest he was acting on behalf of Certified Check and Title (CC&T). It was then revealed that, although this company had deep unofficial ties with Northwestern Bank and its subsidiaries—some of their employees served as officers in CC&T and did that company’s work—the stock was wholly owned by Edwin Duncan, Jr., in trust for his children. When I casually listened to Daddy’s half of the conversations, it never occurred to me to wonder how the deals were financed. It was done by subterfuge: the bank issued loans to Julius “Judy” Womble, the owner-operator of a service station in Sparta, NC, the Duncans’ hometown, but he turned the funds over to CC&T for the purchase of heavy equipment.

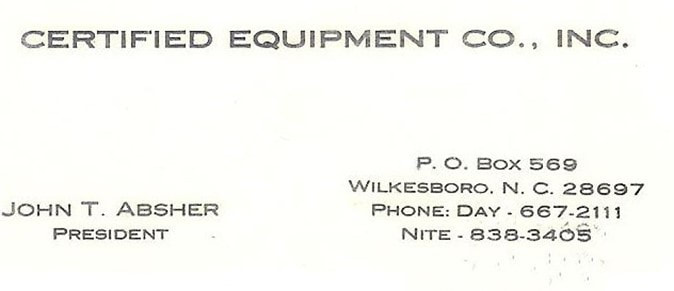

Among Daddy’s papers I found a business card for a company called Certified Equipment showing Daddy as president. I assume that this company was connected to Certified Check and Title, perhaps as a DBA. Certified Equipment is not mentioned in any of the newspaper accounts that I’ve seen.

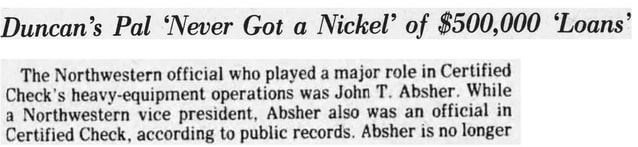

Over the years, Womble “borrowed” half a million dollars in this way, and Daddy was the official who took him the loan papers to sign. I remember the shock I felt twenty years ago when my wife and I were searching through microfilm copies of old newspapers and I came across this story, “Duncan's Pal ‘Never Got a Nickel’ of $500,000 ‘Loans’”:

“The Northwestern official who played a major role in Certified Check's heavy-equipment operations was John T. Absher. While a Northwestern vice president, Absher also was an official in Certified Check, according to public records. Absher is no longer with Northwestern. He could not be reached for comment yesterday....

Womble said that Absher would visit him periodically to have him sign papers. That was the extent of his own involvement, Womble said. Womble said he never saw the equipment and did not ask Absher specific questions about the arrangement.

‘I was used (in the sense of letting his name be put on the loans),’ Womble said, but ‘I was willing to be used.’ He said he would do it again, if asked to.” (1)

Womble estimated that Daddy made “‘8 to 15’” visits for this purpose, but bank sources “said that perhaps almost as many as 20 separate loans were made under Womble's name.” (In case the reader is curious, the issue wasn’t embezzlement: the loans were repaid with interest.) Daddy took me to see Judy once, but I have only a vague recollection of the visit. He was friendly and obliging.

In 1969, the Northwestern Bank became part of the newly organized Northwestern Financial Corporation, a one-bank holding company, with Edwin Duncan, Sr., serving as president of both organizations. In 1971, Booner became the president of the bank, while his father remained president of the holding company. This is the key year for all that followed.

Digression on Timelines

I have been fascinated with timelines since at least the seventh grade. Shortly after moving to North Wilkesboro, in Social Studies class we were assigned to create a timeline. I don’t remember the historical period or geographical area involved, but I think it was US history. I became deeply invested in the project. I don’t remember my sources, but no doubt I used as one source, if not my main source, our old set of Encyclopedia Brittanica published just after the Second World War. I kept adding events and taping paper to paper to lengthen out the years, and finally ended up with a timeline that, unscrolled, must have measured 2-3 feet in length, possibly a good bit longer.

I was at the same time proud of my work—when we shared our timelines in class, mine was easily twice as long as any other—and ashamed: I thought my work was both inadequate to the subject as I understood it, but too much for the assignment. I had made a mistake; I was new to the school and I had inadvertently outed myself as “the smart kid” and as a candidate to be the teacher’s pet. I sensed the resentment of my fellow students. They thought I was showing off and they might have been right.

Over the years, my interest in capturing the past, in outline and chronological form, grew to include personal events, family history, historical events, source works, quotations, and analytical definitions—much too unwieldy to accommodate in a handwritten journal. My handwriting is at times undecipherable, even to me, and arthritis now makes it uncomfortable to write at length by hand. In deciding to methodically gather this material into a sort of commonplace book, I was influenced in part by Walter Benjamin’s Arcades project. (Given Benjamin’s intense focus and analytical power, I realize that this is both a comic and pathetic admission, as is the next.) I started using a tool I had and knew how to use, Excel, though a database would have been far better. My timeline / commonplace files now consist of five Excel worksheets, all but the first organized by date—the date an event occurred, the date a quotation or poem or book was published, the date one of my tweets was posted (I’m no longer an active user), the date someone shared interesting information with me. The remaining file is organized alphabetically by topic. In all, I have made about 8800 entries—not adequate to the topics of interest, but perhaps in excess of any value I might obtain from it.

Timelines can suggest causality; even if post hoc does not mean propter hoc, knowing the sequence of events can be enlightening. What I’ve found more interesting is the revelation of contemporaneity—of similar, unrelated events happening around the same time. I can recall several instances when I was surprised by the contemporaneity of events; at times, the discovery with the force of revelation. Here’s a simple, minor example: My paternal great grandmother Emma died in early November 1963, shortly after I turned twelve. She was the mother of my grandfather, Elbert, who raised Daddy for the two years his mother was in the mental hospital. A couple of weeks later, John F. Kennedy was assassinated; we heard about it on the playground and were quickly summoned to the classroom to sit in silence till dismissed. I was taken aback several years ago when I first realized how close in time these events occurred. I remember my great grandmother’s funeral quite well, and I have even more vivid memories of the assassination—or rather, of newscasts about the assassination. In my mind they exist in two separate spheres that do not touch, though in life they followed one after the other.

Contemporaneity is significant for this essay. My father’s fall began in September 1971 when, at this instigation of his employer, he bugged the office in the bank’s headquarters that the IRS was using to audit the bank. President Nixon’s fall began early in the same month when the White House Plumbers burgled the office of a psychiatrist, Daniel Ellsburg, who had leaked the Pentagon Paper; the Plumbers would go on to plant bugs in the offices of the Democratic National Committee. These two sets of events share characteristics—surveillance and illegality, fear and paranoid suspicion. Once I understood their nearness in time, I found the coincidence to be fraught with significance.

If in the account that follows, we are most concerned with the timeline of my father, and secondarily with the Watergate timeline, but we will also be concerned with two other timelines that link them in a way. The third is the making of The Conversation, a Francis Ford Coppola movie, released in 1974, which at the time was taken as an intentional reflection on Watergate; he claimed it was not, but had existed in concept and in draft scripts since the 1960s. The fourth is the career of Martin Kaiser, who was directly involved in my Daddy’s story and who became collateral damage, though when I questioned him several years ago he claimed, credibly, not to have known Daddy. Kaiser made his career from selling miniature listening devices to the FBI, CIA, and other agencies and organizations. He was also involved as an uncredited technical adviser in the making of The Conversation.

Kaiser may even have manufactured the “bugs” used by the so-called White House Plumbers. I’m not aware of anyone making that claim, but it is not an unreasonable hypothesis. On the DVD commentary for The Conversation (as summarized by Wikipedia), Coppola is “shocked to learn that the film used the same surveillance and wire-tapping equipment that members of the Nixon Administration used to spy on political opponents prior to the Watergate scandal.” He makes two statements to separate his film from a direct connection with the scandal. First, “the script for The Conversation [was] completed in the mid-1960s (before the Nixon Administration came to power)”; second, “the spying equipment used in the film was discovered through research and the use of technical advisers, and not, as many believed, by revelatory newspaper stories about the Watergate break-in.” But, since one of those advisers was Kaiser, well-known for his role in supplying bugs to the world, Coppola’s statement inadvertently reveals a possible connection to Watergate and the Plumber’s listening devices.

A credited technical advisor for the film, Hal Lipset, provides another, more obvious connection with Watergate. Lipset was well-known in government circles. In 1965 he famously performed a stunt for a Senate Subcommittee investigating privacy: he inserted a transmitter inside the fake olive in a cocktail. The stunt garnered a lot of coverage, possibly the reason that Lipset was the inspiration for the protagonist in The Conversation, Harry Caul. (2) Most important, in 1973, at the same time Lipset was advising Coppola, he was “a special consultant to the Watergate Committee” working for Sam Dash. (3) (He was dismissed in April 1974, around the time The Conversation was released, once his 1966 conviction for electronic eavesdropping was revealed by the Nixon administration.) (4)

Through Kaiser and Lipset, The Conversation had a possible connection to the bugging devices used by the Watergate plumbers as well as a definite connection to the Watergate investigation. The origin and conception of the film preceded Watergate and the beginning of the Nixon administration, but its realization on screen probably owes something to the scandal. As we will see, well before Watergate, loss of privacy was a significant issue in the news, the subject of books and articles, hearings on Capitol Hill, and new laws that both protected privacy and opened new areas for government intrusion.

Timelines can teach us something else about personal and social history. As I worked on my timeline / commonplace book, I realized that a full accounting of a quotation or an historical event would need to include the date of the event; the date the quotation was first said or written; the date of the work in which I found it; the date I entered it on the timeline; and, for often-encountered quotations, the source and date of each encounter. Not many years ago I came across, in English, an aphorism by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, “A knife without a blade, for which the handle is missing.” (“Ein Messer ohne Klinge, an welchem der Stiel fehlt”), first recorded in 1798, but first encountered by me in a marvelous poem, “Sublimaze,” by Gjertrud Schnackenberg in her collection, Heavenly Question (2010). I’ve since encountered it in other places, and I could have noted the source and date of each encounter. But this is more than a spreadsheet could accommodate and, except in rare cases, more than I would ever care to account for, unless I were to make every interesting event and quotation I encounter the subject of an essay.

But this fastidious concern with dates points to something real. An event is not confined to the time in which it occurs. An event, including an encounter with a book, lives in memory, it is written about and shared. Time and sharing add to and change the memory. Some aspects are forgotten, though they may emerge much later, transformed by time and a new context. A statement or insight published in a given year may be taken up years later by another work and take on new life. The historian, John Lukacs, is right, I hope: “when it comes to a human event, a later realization that what happened was not what we thought happened usually involves an increase in the quality of our knowledge, together with a decrease in the quantity in our memory” (“The Presence of Historical Thinking,” in Remembered Past).

NOTES:

Note 1: Winston-Salem Journal, 27 July 1977

Note 2: Alex Markels, “Warrantless Wiretaps: A Guide to the Debate,” NPR, 20 Dec 2005, https://www.npr.org/templates/ story/story.php?storyId=5061834). Marty Kaiser claimed he was the inspiration for Caul, a claim reflected in the Wikipedia article on "The Conversation" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Conversation) in March 2024. Both men may have been inspirations for Caul, of course.

Note 3: “Logical advisor for a film on bugging in S.F.,” San Francisco Examiner, 12 Apr 1974

Note 4: Brian Hochman, The Listeners: A History of Wiretapping in the United States, p. 314

Posted 16 March 2024, updated 18 March, 28 March 2024. Second draft: 11 May 2024, updated 16 May 2024. Send comments, questions, and corrections to [email protected].

At first we lived in the cold house at the top of Ninth Street hill, across a side street from the fire department. Every day, the alarm at the fire station signaled the noon hour with a blast of sound that could be heard over much of the town. If I was in the yard, it often made me jump. When a fire was reported, the alarm blasted a code indicating the general location of the fire.

Although I had the best room in the house, with a row of three windows overlooking the yard, I didn't like the house or living in town. Then we moved about ten miles north, to a farmhouse on highway 18. The view was not as interesting as it had been in Jefferson—there was no beautiful mountain looming over the place—but the farmhouse was also set in fields near a large expanse of woods, with a fine old barn and several outbuildings. The kitchen and a nearby outbuilding were connected by a covered breezeway where we sat to hull beans, shuck and silk corn, and slice peaches for canning. It was the best feature of the house, at least in memory.

Not far from the house was a deep gouge in the earth said to have been formed by the flood of 1916, and on a hill nearby was the grave of a distant ancestor, Abraham Absher. It was a place wonderfully suited for our night games of hide and seek. We were living here, on the old Hayes place, when baby brother contracted pneumonia and almost died. While Mom and Daddy spent hours by the hospital bed, our great aunt Maude came to look after us and milk the cow.

Then Daddy bought an old farmhouse, about ten miles south of North Wilkesboro on highway 115, also set in fields near a large woodland. The house had been built by the farmer from whose widow we bought the place. Daddy claimed there wasn’t a plumb corner in the house. It was the first place we had owned since his nervous breakdown in Marion, Virginia, about ten years before. This is the farm mentioned in Part 4 where we often encountered copperheads and rattlesnakes. Daddy had a den and bathroom added to the back of the house before we moved in, and we painted the exterior with a glossy dark brown that was, I think, much more chocolate in color than my parents anticipated; in a certain light, it reflected the trees and bushes around it and turned a muddy green. There was no air conditioning, but at the top of the stairs, over the landing, was a large ceiling fan that sucked in the cooler night air through our open windows and across our sleeping bodies. We were living here when I graduated high school in 1970, attended my first year at BYU, and left for my mission in 1971. Here we were living when Daddy’s life began falling apart, though for a long time it was not visible to me.

An incident occurred here that has stayed with me for a long time because of its suggestive relationship with what followed. In my journal I wrote years afterward:

“From an undated piece of paper inserted in my journal; it was probably written around the time I had lived longer than [Daddy, that is, around 2002, and certainly before my sister's revelations to me in early 2006]:

“‘When I was in high school, I wrote some fantasy about committing suicide. I don’t remember anything about the contents, except a vague recollection of some sort of parade that somehow illustrated my character flaws, as I saw them, and moments of humiliation; it was written, I think, in red ink. Mama or Daddy found this story [in my bedroom] and were genuinely concerned. Daddy asked me to promise that I would never kill myself. I promised, and though I did not have time to consider it (he had caught me off-guard), my promise was completely serious. When I was depressed for all those years, though I was not consciously considering suicide (Martha [my wife at the time] thought I was, she told me later, and felt trapped by it), the memory of that promise was something that gave me a glimmer of hope, for I knew that I would never bottom out into self-annihilation. I knew I would keep the promise.’

“Until last night, I’d never realized the irony of this episode. I started to feel again the anger I’ve been feeling lately—not overwhelming or ruinous as it felt years ago, but peeking out at unexpected times. Very unpleasant. Today I realized that I’d never let myself feel anger at Daddy for abandoning us, for leaving Mom with so few assets, and all of us (I'm sure) with unsettled issues. Perhaps I was angriest because he had acted so stupidly, as if he had no other choices. Because he gave up on his early dreams so damned easily. Because he faced a horrible challenge and did not triumph. Because I’ve outlived him in years and yet feel, with all his faults, that I’m not half the man he was. Because [my son] John couldn’t know him (the hardest thing of all).”

Years later I wrote a poem about the incident:

He Came to Me

He came to me. Evening was in the sky,

pinking the east, graying the west, the wave

of darkness rising. We didn’t mean to pry.

Your mama found this in your room and gave

this poem to me. (He held my fantasy

about suicide.) Son, will you swear

never to do this to us? When he sweetly

took my hand—the left—I was half-scared,

but gave my covenant. And I have kept it,

though he broke faith, slipping down a hole

in the world that nearly pulled me through.

The breach is plugged for now with blood and spit.

Sometimes it leaks radiance, a dark blue.

I will go there when I can go whole.

(Visions International, 2009)

But, to return to our narrative, when Daddy first joined the bank, he was involved in selling repossessed equipment and vehicles. I don’t know his title then, but soon he became a vice president. The bank had many of them. Above them were senior vice presidents; Booner had become a VP in 1958, then senior VP in 1964. There were also executive vice presidents; so far as I can tell from contemporary newspaper articles, most of the executive VPs had overall responsibility for the bank’s operations in a town or city. But there was at least one exception: at some point (I don’t know when), Daddy was promoted to be executive vice president of Consumer Relations.

Though I did not know this until many years after his death, Daddy also had a position in another company, Certified Check and Title. I remember a few occasions when he would get on the phone and make long-distance calls to potential sellers and buyers of heavy equipment. I assumed this was his own side business, but testimony and news stories in 1976 and 1977 suggest he was acting on behalf of Certified Check and Title (CC&T). It was then revealed that, although this company had deep unofficial ties with Northwestern Bank and its subsidiaries—some of their employees served as officers in CC&T and did that company’s work—the stock was wholly owned by Edwin Duncan, Jr., in trust for his children. When I casually listened to Daddy’s half of the conversations, it never occurred to me to wonder how the deals were financed. It was done by subterfuge: the bank issued loans to Julius “Judy” Womble, the owner-operator of a service station in Sparta, NC, the Duncans’ hometown, but he turned the funds over to CC&T for the purchase of heavy equipment.

Among Daddy’s papers I found a business card for a company called Certified Equipment showing Daddy as president. I assume that this company was connected to Certified Check and Title, perhaps as a DBA. Certified Equipment is not mentioned in any of the newspaper accounts that I’ve seen.

Over the years, Womble “borrowed” half a million dollars in this way, and Daddy was the official who took him the loan papers to sign. I remember the shock I felt twenty years ago when my wife and I were searching through microfilm copies of old newspapers and I came across this story, “Duncan's Pal ‘Never Got a Nickel’ of $500,000 ‘Loans’”:

“The Northwestern official who played a major role in Certified Check's heavy-equipment operations was John T. Absher. While a Northwestern vice president, Absher also was an official in Certified Check, according to public records. Absher is no longer with Northwestern. He could not be reached for comment yesterday....

Womble said that Absher would visit him periodically to have him sign papers. That was the extent of his own involvement, Womble said. Womble said he never saw the equipment and did not ask Absher specific questions about the arrangement.

‘I was used (in the sense of letting his name be put on the loans),’ Womble said, but ‘I was willing to be used.’ He said he would do it again, if asked to.” (1)

Womble estimated that Daddy made “‘8 to 15’” visits for this purpose, but bank sources “said that perhaps almost as many as 20 separate loans were made under Womble's name.” (In case the reader is curious, the issue wasn’t embezzlement: the loans were repaid with interest.) Daddy took me to see Judy once, but I have only a vague recollection of the visit. He was friendly and obliging.

In 1969, the Northwestern Bank became part of the newly organized Northwestern Financial Corporation, a one-bank holding company, with Edwin Duncan, Sr., serving as president of both organizations. In 1971, Booner became the president of the bank, while his father remained president of the holding company. This is the key year for all that followed.

Digression on Timelines

I have been fascinated with timelines since at least the seventh grade. Shortly after moving to North Wilkesboro, in Social Studies class we were assigned to create a timeline. I don’t remember the historical period or geographical area involved, but I think it was US history. I became deeply invested in the project. I don’t remember my sources, but no doubt I used as one source, if not my main source, our old set of Encyclopedia Brittanica published just after the Second World War. I kept adding events and taping paper to paper to lengthen out the years, and finally ended up with a timeline that, unscrolled, must have measured 2-3 feet in length, possibly a good bit longer.

I was at the same time proud of my work—when we shared our timelines in class, mine was easily twice as long as any other—and ashamed: I thought my work was both inadequate to the subject as I understood it, but too much for the assignment. I had made a mistake; I was new to the school and I had inadvertently outed myself as “the smart kid” and as a candidate to be the teacher’s pet. I sensed the resentment of my fellow students. They thought I was showing off and they might have been right.

Over the years, my interest in capturing the past, in outline and chronological form, grew to include personal events, family history, historical events, source works, quotations, and analytical definitions—much too unwieldy to accommodate in a handwritten journal. My handwriting is at times undecipherable, even to me, and arthritis now makes it uncomfortable to write at length by hand. In deciding to methodically gather this material into a sort of commonplace book, I was influenced in part by Walter Benjamin’s Arcades project. (Given Benjamin’s intense focus and analytical power, I realize that this is both a comic and pathetic admission, as is the next.) I started using a tool I had and knew how to use, Excel, though a database would have been far better. My timeline / commonplace files now consist of five Excel worksheets, all but the first organized by date—the date an event occurred, the date a quotation or poem or book was published, the date one of my tweets was posted (I’m no longer an active user), the date someone shared interesting information with me. The remaining file is organized alphabetically by topic. In all, I have made about 8800 entries—not adequate to the topics of interest, but perhaps in excess of any value I might obtain from it.

Timelines can suggest causality; even if post hoc does not mean propter hoc, knowing the sequence of events can be enlightening. What I’ve found more interesting is the revelation of contemporaneity—of similar, unrelated events happening around the same time. I can recall several instances when I was surprised by the contemporaneity of events; at times, the discovery with the force of revelation. Here’s a simple, minor example: My paternal great grandmother Emma died in early November 1963, shortly after I turned twelve. She was the mother of my grandfather, Elbert, who raised Daddy for the two years his mother was in the mental hospital. A couple of weeks later, John F. Kennedy was assassinated; we heard about it on the playground and were quickly summoned to the classroom to sit in silence till dismissed. I was taken aback several years ago when I first realized how close in time these events occurred. I remember my great grandmother’s funeral quite well, and I have even more vivid memories of the assassination—or rather, of newscasts about the assassination. In my mind they exist in two separate spheres that do not touch, though in life they followed one after the other.

Contemporaneity is significant for this essay. My father’s fall began in September 1971 when, at this instigation of his employer, he bugged the office in the bank’s headquarters that the IRS was using to audit the bank. President Nixon’s fall began early in the same month when the White House Plumbers burgled the office of a psychiatrist, Daniel Ellsburg, who had leaked the Pentagon Paper; the Plumbers would go on to plant bugs in the offices of the Democratic National Committee. These two sets of events share characteristics—surveillance and illegality, fear and paranoid suspicion. Once I understood their nearness in time, I found the coincidence to be fraught with significance.

If in the account that follows, we are most concerned with the timeline of my father, and secondarily with the Watergate timeline, but we will also be concerned with two other timelines that link them in a way. The third is the making of The Conversation, a Francis Ford Coppola movie, released in 1974, which at the time was taken as an intentional reflection on Watergate; he claimed it was not, but had existed in concept and in draft scripts since the 1960s. The fourth is the career of Martin Kaiser, who was directly involved in my Daddy’s story and who became collateral damage, though when I questioned him several years ago he claimed, credibly, not to have known Daddy. Kaiser made his career from selling miniature listening devices to the FBI, CIA, and other agencies and organizations. He was also involved as an uncredited technical adviser in the making of The Conversation.

Kaiser may even have manufactured the “bugs” used by the so-called White House Plumbers. I’m not aware of anyone making that claim, but it is not an unreasonable hypothesis. On the DVD commentary for The Conversation (as summarized by Wikipedia), Coppola is “shocked to learn that the film used the same surveillance and wire-tapping equipment that members of the Nixon Administration used to spy on political opponents prior to the Watergate scandal.” He makes two statements to separate his film from a direct connection with the scandal. First, “the script for The Conversation [was] completed in the mid-1960s (before the Nixon Administration came to power)”; second, “the spying equipment used in the film was discovered through research and the use of technical advisers, and not, as many believed, by revelatory newspaper stories about the Watergate break-in.” But, since one of those advisers was Kaiser, well-known for his role in supplying bugs to the world, Coppola’s statement inadvertently reveals a possible connection to Watergate and the Plumber’s listening devices.

A credited technical advisor for the film, Hal Lipset, provides another, more obvious connection with Watergate. Lipset was well-known in government circles. In 1965 he famously performed a stunt for a Senate Subcommittee investigating privacy: he inserted a transmitter inside the fake olive in a cocktail. The stunt garnered a lot of coverage, possibly the reason that Lipset was the inspiration for the protagonist in The Conversation, Harry Caul. (2) Most important, in 1973, at the same time Lipset was advising Coppola, he was “a special consultant to the Watergate Committee” working for Sam Dash. (3) (He was dismissed in April 1974, around the time The Conversation was released, once his 1966 conviction for electronic eavesdropping was revealed by the Nixon administration.) (4)

Through Kaiser and Lipset, The Conversation had a possible connection to the bugging devices used by the Watergate plumbers as well as a definite connection to the Watergate investigation. The origin and conception of the film preceded Watergate and the beginning of the Nixon administration, but its realization on screen probably owes something to the scandal. As we will see, well before Watergate, loss of privacy was a significant issue in the news, the subject of books and articles, hearings on Capitol Hill, and new laws that both protected privacy and opened new areas for government intrusion.

Timelines can teach us something else about personal and social history. As I worked on my timeline / commonplace book, I realized that a full accounting of a quotation or an historical event would need to include the date of the event; the date the quotation was first said or written; the date of the work in which I found it; the date I entered it on the timeline; and, for often-encountered quotations, the source and date of each encounter. Not many years ago I came across, in English, an aphorism by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, “A knife without a blade, for which the handle is missing.” (“Ein Messer ohne Klinge, an welchem der Stiel fehlt”), first recorded in 1798, but first encountered by me in a marvelous poem, “Sublimaze,” by Gjertrud Schnackenberg in her collection, Heavenly Question (2010). I’ve since encountered it in other places, and I could have noted the source and date of each encounter. But this is more than a spreadsheet could accommodate and, except in rare cases, more than I would ever care to account for, unless I were to make every interesting event and quotation I encounter the subject of an essay.

But this fastidious concern with dates points to something real. An event is not confined to the time in which it occurs. An event, including an encounter with a book, lives in memory, it is written about and shared. Time and sharing add to and change the memory. Some aspects are forgotten, though they may emerge much later, transformed by time and a new context. A statement or insight published in a given year may be taken up years later by another work and take on new life. The historian, John Lukacs, is right, I hope: “when it comes to a human event, a later realization that what happened was not what we thought happened usually involves an increase in the quality of our knowledge, together with a decrease in the quantity in our memory” (“The Presence of Historical Thinking,” in Remembered Past).

NOTES:

Note 1: Winston-Salem Journal, 27 July 1977

Note 2: Alex Markels, “Warrantless Wiretaps: A Guide to the Debate,” NPR, 20 Dec 2005, https://www.npr.org/templates/ story/story.php?storyId=5061834). Marty Kaiser claimed he was the inspiration for Caul, a claim reflected in the Wikipedia article on "The Conversation" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Conversation) in March 2024. Both men may have been inspirations for Caul, of course.

Note 3: “Logical advisor for a film on bugging in S.F.,” San Francisco Examiner, 12 Apr 1974

Note 4: Brian Hochman, The Listeners: A History of Wiretapping in the United States, p. 314

Posted 16 March 2024, updated 18 March, 28 March 2024. Second draft: 11 May 2024, updated 16 May 2024. Send comments, questions, and corrections to [email protected].