Night scene on the battlefield, showing Verey lights being fired from the trenches, Thiepval, 7 August 1916. (https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205072490) In “Nocturne,” the final poem of Henry-Jacques I have translated so far, a night in the trenches becomes a dark night of the soul. He is becoming part of the darkness; the darkness is becoming part of him. He must find a new language—using words that war “has not stained”—to understand the shadow, both “hard” and “ungraspable,” that holds him.

Nocturne by Henry-Jacques Cold night, with supple tentacles winding round the neck and shoulder: here I am, I don’t know where, stooping in a narrow cell. From the pit around me rise the arcana, opaque and hard. I grope the earth as if fumbling cards. Tonight hands must be my eyes. Like a beast in the teeth of a snare, my will contorts itself, dismayed that in this gloom I am no more than shadow merging into shade. I feel as if I were being poured into hard, ungraspable shadow that, through fissures I cannot see and without noise, slips into me. The mind, mustering all its power to leave the dark in which it’s caught, floats like wood, emptied of thought, on the black, slow-moving water. It hears the murky silence made of whispering voices in the thousands flowing together in human currents. Huddled in the trench we wait. A little more and the naked mind dares question its fate; and now, escaping the words that war has stained, it senses truths it never knew. And from the throat of the pit a noise rises, a funereal voice: “What are you doing in this shadow?” And my heart responds, “I do not know.”

0 Comments

Source: Pinterest UK Henry-Jacque’s first collection of poems on the First World War is called La Symphonie héroïque; it won a prize, the Prix de la Renaissance, in 1922. Henry-Jacques (1886 - 1973) was a pseudonym; his name at birth was Henri Edmond Jacques. The title and structure of the book reflect his interest in music; after the war, he published two music journals and was recognized as a musicologist. In addition to two other books of poetry based on his wartime experiences, he was a journalist, a novelist, an adventurer at sea. He circumnavigated the globe several times, twice sailing around Cape Horn.

In “Landscapes” (“Paysages”), a soldier is entering the trenches and marching towards the dangerous front line to work as an observer, as in the poem I recently posted, “Assassin Poet.” As other stories and poems from the war reveal, the trenches were confusing and disorienting, even for an experienced soldier; the aerial photo above gives some idea. The front and the war were, as the poem says, everywhere. Enemy planes, mines placed by sappers in tunnels under the trenches, artillery shells, and gas attacks affected far more than the designated front line. Landscapes by Henry-Jacques I. In the wall, wide as a porch, a hole that opens on a hole, barbed wire that flays the skin. A hand notice riddled with holes: "Trench four, to the lines,” to war, over there, everywhere. As black as vine shoots, the pickets all skin and bone show their signs as they stand watch on top of sacks cast up on this petrified sea. II Before you is the gate of hell; pass through, but watch out for the front, that too vague something: the front. It’s there, above, below, in the air, deep opening into deep, impalpable, an anguish clinging to the flesh. There, where your eyes come to rest, that ridge—it’s near yet very far, the end of the world, that low crest, right there… a little farther… a bit less. III A little closer, a little farther… the trench runs to every quarter; drifting away but never moving, everywhere and nowhere fleeing in broken angles of separation that snap even the greatest strength. But fighting the weary, dejected fear of anything that moves or stirs, of even the air tense with silence, the heart divines that it is there! IV The outpost’s distrustful eye, its furtive spyhole, narrow transom cut in the never-ending wall. Stretching outward his watchful mind, a man looks through the hole and hazards his eye to those he cannot trust. He scrutinizes the soul of war, but sometimes, slipping across the edge, his gaze takes in the whole of death beyond life, beyond the earth.  Wire grass, or bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) Wire grass, or bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), is a nonnative perennial grass. Like many weeds that come to the casual gardener’s attention, it is persistent and hard to remove. It spreads by above-ground runners (called stolons) and underground rhizomes that can reach a foot or more into the ground. Its stem is tough, and I surmise the origin of its name. It’s said that the plant can grow back from small sections of a stolon or rhizome. It is not a pretty plant, but I find a certain elegance in its leggy architecture.

I had this sprig sit for a photoshoot this afternoon. I’m digging up part of our front lawn for a bed of perennial native plants and the occasional annual. It’s a sunny spot. I welcome recommendations. Message me on Facebook or send an email to [email protected].  French front line trenches, c. 1916 (source: Once Upon a Time in War, https://demons.swallowthesky.org/tagged/World%20War%20I%3A%20French%20Troops/page/5) Henry-Jacques was a French soldier in the trenches in the First World War. He’s obscure by any standard, but his poems were republished a few years ago as part of the commemoration of the war.

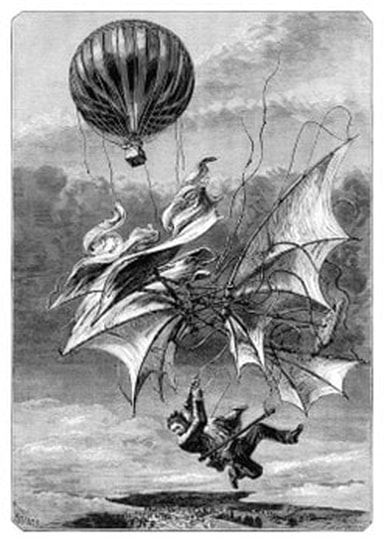

This poem captures a peaceful moment in the war that nevertheless ends in death. The narrator sees himself in the dreams and struggles he ascribes to the German soldier, but his internal debate ends in his pulling the trigger. The poem captures many truths of the war, as I know them through reading, with this striking one: any relaxation of discipline or momentary lack of fear that led a soldier to poke his head above the parapet of the trench was likely to end in his death. Much of the poem reminds me of Thomas Hardy's well-known poem, "The Man He Killed." Assassin Poet The languor of the autumn sun ennobles the Forest of Argonne, that wounded wood where, knocked to the grass, the trees are dead; or left in ruin, leafless, branches hacked, trunks scarred; or cut to the ground and black as timbers in a mine. The paths are no more now than the narrow hallways we traverse seeing nothing all day but a patch of sky, the ghost of an oak that leans and holds out a branch, or all of it that remains; stacked sandbags; logs scattered amid broken armor; a treacherous loophole where a well-placed bullet suddenly gets you in the gullet: This is the frontier, the barricade where lurk the watchers of the war. Like the others, I am here, eyes alert and sharp, hearing acute-- small task, enormous duty to be guardian of the route. My rifle loses its coldness in my hands-- and what if a fired-up German were to rise from his trench and run right at me? I can see his lines, the pickets knocked sideways, the broken strands of wire, the green-bellied sacks; and—souvenir of some futile fight-- in the dirt, a cadaver trembling with swarms of flies. But this day of calm and sun has so much charm for the men placed under arms that a kind of sleep like new wine appeases the desire to rage and murder. A great hush, a great sweetness, a new song soars over us. My marveling heart, my sun-reveling heart, my heart for once escapes the fight and, freed from its immense duty, ascends into the light resurrected to love and hope and beauty. But above a gap in the trenches, a cap, a head appear: a man we face is being drawn out by the dream-- the clear sky’s perfect tenderness, the song lost overhead in the white depths of a cloud, the giddy sweetness he drinks in, his piercing hope of living on. So near, so far, O soldier I do not know, in this moment I do not hate you; man in green, man in blue, aren’t we the same? In this moment, you and I—we think the same. —My rifle is suddenly heavy in my hands-- Dream on, ignore the watching man, The unknown poet who has you in his hands. —What’s this cartridge for?-- We are both of us alike in the sunlight. —The stock rises to my cheek, ready to fire-- Isn’t war a shameful thing? — O instinct for savagery that springs from histories we know not of-- Keep dreaming, thoughtful enemy, I do not wish your death. —My finger is on the trigger, squeezes-- What use is any fresh regret? —A gunshot in the wood called La Grurie-- I see his cap fly off. I cannot see his head. The song flies off into the wood. Such is war: not winning or losing, But a man, like me, in a fate not of his choosing. Pity is all I felt for him, And I killed him.  This illustration by an artist named Miranda from around 1874 depicts the fatal failure of a flying apparatus. The self-styled “Flying Man” fell from the skies over London. It’s an apt metaphor for those betrayed by their own lies. (https://www.oldbookillustrations.com/illustrations/de-groof-falling/) We are entering the height of the political season that begins with the conventions and ends only in mid-December with the selection of the president by the electors or even, as we have recently seen, with the counting of the electoral votes by the House of Representatives in early January. In past years, we would have said that the season ended with election day, but such is no longer reliably the case. Indeed, in contrasts with years gone by, we hardly ever leave the political season. Still, the stakes and tensions become higher now.

A political season is a season of half-truths, of lies ugly and beautiful, of disputed facts and credible fictions. Sometimes, at its best, it’s a season of enunciating first principles and attempting virtuous persuasion. Now it seems more like a season of violence. This is not progress. This is not the arc of history bending toward justice. We are conjuring the “ever-threatening storms / Of Chaos blustering round” (Paradise Lost, III. 425). Violence is the child of Chaos by Lies. It seems an appropriate moment to reconsider a poem by Rilke, “Mensonge II” (“Lie II”). I first posted my tentative translation on 1 May 2023. Although I have since revised it, it is still a rough draft--all my translations of Rilke's poems are like sandpaper to silk. Rilke is best known, of course, as a great German poet, but at the end of his life he wrote many short poems in French, including “Mensonge II.” The poem’s many metaphors (sometimes verging on allegory) are insightful. The lie is an amphora with no feet: it must be lifted and held by the liar since it can’t stand on its own (section 2). The lie is an islet on a map that does not correspond to reality (section 3). It is a human construct, a “work of the eighth day” of creation; unlike the apple on the tree of life, it’s meant for God to eat (section 3). I originally wrote that Section 4 is about complicity in lies, and as such is quite troubling. But the scene set by the section’s four lines also suggests a mutual seduction—a wink, an eloquent silence, a hidden conspiracy; it suggests an echo chamber where everyone knows there’s a lie, no one admits who started it ("Did I call you?"), no one is willing to challenge it. The lie is a thin smile for which we must suitably make up a face (section 5). It is so beautiful that beside it we feel fake (section 6). We’re all tempted to say, “Yes, I know, my side has its little fibs and pious fictions, but those guys over there, Goebbels holds their beer.” But I try always to remember this: “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either -- but right through every human heart -- and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained.”―Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918–1956 Please send comments, suggestions, and critiques to [email protected]. Lie II by Rainer Maria Rilke 1. Lie, a toy we break. Garden where we change places the better to hide; yet where at times we cry out to be half found. Wind, singing for us, our shadow, growing long. Collection of handsome holes in our sponge. 2. Mask? No. You are more complete, lie, your eyes are eloquent. More like a vase without a foot, amphora wanting to be in hand. Your foot has no doubt been swallowed by your handles. Whoever carries you seems to complete you, were the movement with which he lifts you not so remarkable. 3. Are you flower, are you bird, lie? Are you scarcely word or word and a half? What pure silence surrounds you, beautiful new islet; maps don’t know your provenance. Late-comer to creation, work of the eighth day, posthumous. Since it’s we who make you, it must be God who consumes. 4. Did I call you? But of what word, what gesture am I guilty of a sudden, if your silence cries to me, if your eyelid winks at me with tacit understanding? 5. For this meager smile how can a face be found? Better if a cheek agrees to put this makeup on. Lying is in the air, like this marquee that once we burned, completely grayed by its life upside-down. 6. I’m not making myself clear. We close our eyes, we leap, an act almost devout with God at least. After, we open our eyes because we’re being eaten by regret: next to a lie so beautiful, don’t we seem counterfeit? NOTE: “handsome holes” I swiped from A. Poulin’s translation of this poem. Here’s the original: Mensonge II 1. Mensonge, jouet que l’on casse. Jardin où l’on change de place, pour mieux se cacher ; où pourtant, parfois, on jette un cri, pour être trouvé à demi. Vent, qui chante pour nous, ombre de nous, qui s’allonge. Collection de beaux trous dans notre éponge. 2. Masque ? Non. Tu es plus plein, mensonge, tu as des yeux sonores. Plutôt vase sans pied, amphore qui veut qu’on la tient. Tes anses, sans doute, ont mangé ton pied. On dirait que celui qui te porte, t’achève, n'était le mouvement dont il te soulève, si singulier. 3. Es-tu fleur, es-tu oiseau, mensonge ? Es-tu à peine mot ou mot et demi ? Quel pure silence t’entoure, bel îlot nouveau dont les cartes ignorent la provenance. Tard-venu de la création, œuvre du huitième jour, posthume. Puisque c’est nous qui te faisons, il faut croire que Dieu te consume. 4. T’ai-je appelé ? Mais de quel mot, de quel signe suis-je coupable soudain, si ton silence me crie, si ta paupière me cligne d’un accord souterrain ? 5. À ce sourire épars comment trouver un visage ? On voudrait qu’une joue e’engage à mettre ce fard. Il y a du mensonge dans l’air, comme, autrefois, cette marquise qu’on a brûlée, toute grise de la vie à l’envers. 6. Je ne m’explique point. On ferme les yeux, on saute ; c’est chose presque dévote avec Dieu au moins. On ouvre les yeux après, parce qu’un remord nous ronge : à côté d’un si beau mensonge, ne semble-t-on contrefait ? Edited 15 July 2024; revised 16 July 2024 |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed