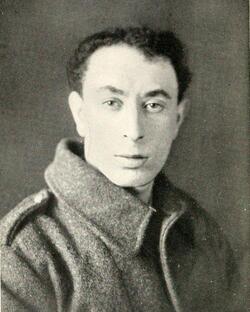

Isaac Rosenberg Source: https://mypoeticside.com/poets/isaac-rosenberg-poems January 1916

“[T]he last British troops left Cape Helles on the Gallipoli Peninsula. … Thirty-three Commonwealth war cemeteries on the peninsula contain the graves of those whose bodies were found. On the grave of Gunner J.W. Twamley his next of kin caused the lines to be inscribed: Only a boy but a British boy, The son of a thousand years. A bereaved Australian sent the following lines: Brother Bill a sniping fell: We love him still, We always will. From parents whose grief could not find comfort in religion came the question: What harm did he do Thee, O Lord?” [Source: Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History] ***** February Afternoon by Edward Thomas Men heard this roar of parleying starlings, saw, A thousand years ago even as now, Black rooks with white gulls following the plough So that the first are last until a caw Commands that last are first again, – a law Which was of old when one, like me, dreamed how A thousand years might dust lie on his brow Yet thus would birds do between hedge and shaw. Time swims before me, making as a day A thousand years, while the broad ploughland oak Roars mill-like and men strike and bear the stroke Of war as ever, audacious or resigned, And God still sits aloft in the array That we have wrought him, stone-deaf and stone-blind. [Source: Dominic Hibberd and John Onions, The Winter of the World] ***** Spreading Manure by Rose Macaulay There are forty steaming heaps in the one tree field, Lying in four rows of ten, They must be all spread out ere the earth will yield As it should (And it won’t, even then). Drive the great fork in, fling it out wide; Jerk it with a shoulder throw, The stuff must lie even, two feet on each side. Not in patches, but level…so! When the heap is thrown you must go all round And flatten it out with the spade, It must lie quite close and trim till the ground Is like bread spread with marmalade. The north-east wind stabs and cuts our breaths, The soaked clay numbs our feet, We are palsied like people gripped by death In the beating of the frozen sleet. I think no soldier is so cold as we, Sitting in the frozen mud. I wish I was out there, for it might be A shell would burst to heat my blood. I wish I was out there, for I should creep In my dug-out and hide my head, I should feel no cold when they lay me deep To sleep in a six-foot bed. I wish I was out there, and off the open land: A deep trench I could just endure. But things being other, I needs must stand Frozen, and spread wet manure. [Source: The Winter of the World] Editors’ note: In England, “many women volunteered to replace men as land workers; like soldiers in the trenches, they suffered in the exceptionally harsh winter of 1916–17.” The winter was harsh throughout Europe and was particularly hard on soldiers in wet trenches, civilians in blockaded economies like Germany’s, and on prisoners of war, especially those who, like Russian soldiers, were not assisted by their governments. Alexei Zyikov, a Russian soldier from Moscow, was captured in 1915 and in 1916 was being held in Marienburg POW camp in north-eastern Germany. In his first diary entry he wrote: “Hunger does not give you a moment's peace and you are always dreaming of bread: good Russian bread! There is consternation in my soul when I watch people hurling themselves after a piece of bread and a spoonful of soup.… We work from dawn till dusk, sweat mingling with blood; we curse the blows of the rifle butts; I find myself thinking about ending it all, such are the torments of my life in captivity! [He had been held for 11 months.] On Sunday we did no work but stood around outside our huts under the gaze of the Germans with their wives and children, full of curiosity and hate watching us from their windows and from the street. And, it was wonderful, they could see that we were people too and they began to come a little closer. But then some of the little German children began hurling stones at us.… [N]othing surprises me here - like today, I saw a soldier rummaging in a rubbish pit, picking out potato and swede peelings and eating them slowly to make them last. The hunger is dreadful: you feel it constantly, day and night. You have to forget who you once were and what you've become.” Zyikov's entries stopped in 1917. His fate is unknown. His diary was discovered in WW2 by Russian soldiers who had invaded the Third Reich. [Source: Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis, ed. A War in Words: The First World War in Diaries and Letters] ***** Returning, We Hear the Larks by Isaac Rosenberg Sombre the night is: And, though we have our lives, we know What sinister threat lurks there. Dragging these anguished limbs, we only know This poison-blasted track opens on our camp-- On a little safe sleep. But hark! Joy—joy—strange joy. Lo! Heights of night ringing with unseen larks: Music showering on our upturned listening faces. Death could drop from the dark As easily as song-- But song only dropped, Like a blind man's dreams on the sand By dangerous tides; Like a girl's dark hair, for she dreams no ruin lies there, Or her kisses where a serpent hides. [Source: The Winter of the World] ***** In the summer of 1916, Rosenberg, then serving in France, looked back on the war’s beginning: August 1914 What in our lives is burnt In the fire of this? The heart’s dear granary? The much we shall miss? Three lives hath one life – Iron, honey, gold. The gold, the honey gone – Left is the hard and cold. Iron are our lives Molten right through our youth. A burnt space through ripe fields A fair mouth’s broken tooth. [Source: The Winter of the World] Edited 12 November 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed