|

The entries below were written by a British civilian, a Russian soldier on the Eastern Front, a thirteen-year-old Prussian schoolgirl, a widow in a besieged city in Galicia, British soldiers in Flanders and the Dardanelles, a Turkish officer in the Dardanelles, an unknown Austrian officer fighting the Italians in the Alps, Rudyard Kipling (whose son John had been killed in unknown circumstances in France), and Thomas Hardy.

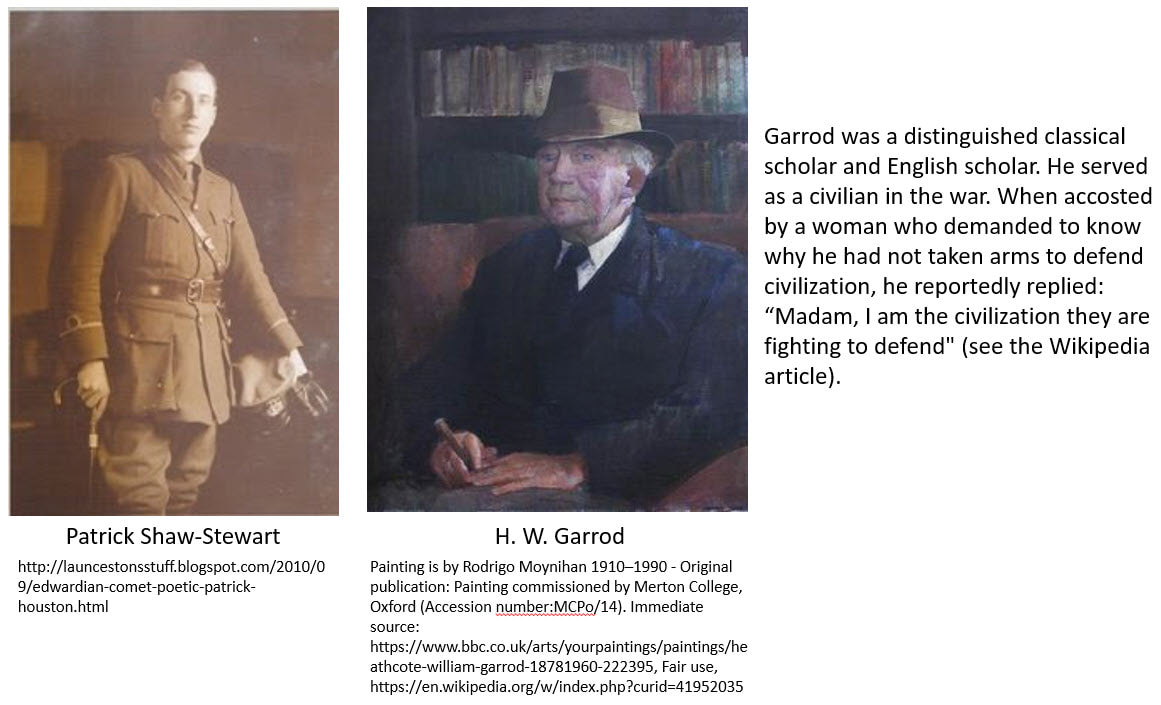

Epitaph: Neuve Chapelle by H.W. Garrod Tell them at home, there's nothing here to hide: We took our orders, asked no questions, died. [Source: Dominic Hibberd and John Onions, The Winter of the World] ***** In his journal entry for 27 January, Russian soldier Vasily Mishnin describes being under artillery fire. The men break and run. Mishnin and a comrade hide in a hut: "We press ourselves against a wall, sit down and wipe our tears. Our eyes are full of tears, we wipe them away, but they just keep coming because the shells are full of gas. We are terrified. [We] lie face down and we just want to dig ourselves into the earth. Under our breath we pray to our Lord God to save us from this, just for this one day. Dear Nyurochka [his wife], pray for me in this terrible hour, and forgive me if I am guilty of anything. Dear God, are you really sitting up there in heaven without hearing or saying anything?" [Svetlana Palmer and Sarah Wallis, ed. A War in Words: The First World War in Diaries and Letters] ***** On March 11, the Prussian schoolgirl, Piete Kuhr, wrote in her journal: “Another collection has been announced at school, for copper, again, but also for tin, lead, zinc, brass and old iron to make gun-barrels, field guns, cartridge cases and so forth. There is a keen competition between the classes. Our class, the fourth, has so far collected the most. I turned the whole house over from top to bottom. Grandma cried, 'the wench will bankrupt me! Why don't you give them your lead soldiers instead of cleaning me out!' So my little army had to meet their deaths.” ***** Helena Seifertóv Jabłońska was trapped by the Russian army in a besieged fortress city in Galicia, a province of Austria-Hungary. She had refused to leave because she did not want to abandon her husband’s grave. On March 15, she wrote: ”The Russians have burned nearly all the surrounding villages. In one village the inhabitants locked themselves into their huts to keep out the Russians. The Russians boarded up the doors from the outside and set fire to the huts. There is no longer any doubt that we will have to surrender. Betrayal and hunger have exhausted us. .... [The soldiers] are mere shadows, not people, they are skeletons, not men. The peasants have had everything taken from them, so as not to leave anything for the Russians. This was done ruthlessly, without any compassion. An act unworthy of the civilised Catholic nation that we are. It was cruel to give such an order, but those executing it were crueller still. How generous of them to leave the peasants their lives!” ***** Sidney Appleyard remembered a soldiers’ marching song from May 1915 in Flanders written by the “platoon poet, Bill Bright”: I’m a bomber, I'm a bomber Wearing a grenade, The Army's got me where it wants, I'm very much afraid. When decent jobs are going I never get a chance, Which shows what bloody fools we were To volunteer for France." [Source: Andrew Roberts, Elegy: The First Day on the Somme] ***** In the Gallipoli campaign, a British officer at Cape Helles wrote about returning to the front after a brief leave: 'I saw a man this morning' by Patrick Shaw-Stewart I saw a man this morning Who did not wish to die: I ask, and cannot answer, If otherwise wish I. Fair broke the day this morning Against the Dardanelles; The breeze blew soft, the morn's cheeks Were cold as cold sea-shells. But other shells are waiting Across the Aegean Sea, Shrapnel and high explosive, Shells and hells for me. O hell of ships and cities, Hell of men like me, Fatal second Helen, Why must I follow thee? Achilles came to Troyland And I to Chersonese: He turned from wrath to battle, And I from three days' peace. Was it so hard, Achilles, So very hard to die? Thou knewest, and I know not-- So much the happier I. I will go back this morning From Imbros over the sea; Stand in the trench, Achilles, Flame-capped, and shout for me. Two years later, Shaw-Stewart was killed on the Western Front. This poem—his only surviving complete poem—was found after his death in his copy of Housman’s A Shopshire Lad. [Hibberd and Onions, The Winter of the World: Poems of the Great War] ***** On 22 November, Mehmed Fasih, a Turkish officer fighting opposite Shaw-Stewart, wrote in his diary: “05.00 hrs. Daydream about a happy family and nice kids. Will I live to see the day when I have some? I know I should be infinitely grateful for what I do have, but why have I not, to this day, been able to find real happiness, the kind that sets the heart free and brings comfort to the soul? Dear God! Will you ever grant such things to be my lot in life?” [A War in Words] ***** From the diary of an unknown Austrian officer, 18th July 1915, fighting the Italian army in the Alps: “In the night the artillery fire became insanely heavy. This is the end, I thought, and prepared to die like a proper Christian. But I am still so young! To die without a confession, without the words of comfort and faith of our holy religion! Oh Italy, may God punish your king and your treacherous people.” [A War in Words] ***** The Children By Rudyard Kipling These were our children who died for our lands: they were dear in our sight. We have only the memory left of their home-treasured sayings and laughter. The price of our loss shall be paid to our hands, not another’s hereafter. Neither the Alien nor Priest shall decide on it. That is our right But who shall return us the children? At the hour the Barbarian chose to disclose his pretences, And raged against Man, they engaged, on the breasts that they bared for us, The first felon-stroke of the sword he had long-time prepared for us – Their bodies were all our defence while we wrought our defences. They bought us anew with their blood, forbearing to blame us, Those hours which we had not made good when the judgment o’ercame us. They believed us and perished for it. Our statecraft, our learning Delivered them bound to the Pit and alive to the burning Whither they mirthfully hastened as jostling for honour – Not since her birth has our Earth seen such worth loosed upon her. Nor was their agony brief, or once only imposed on them. The wounded, the war-spent, the sick received no exemption: Being cured they returned and endured and achieved our redemption, Hopeless themselves of relief, till Death, marvelling, closed on them. That flesh we had nursed from the first in all cleanness was given To corruption unveiled and assailed by the malice of Heaven – By the heart-shaking jests of Decay where it lolled on the wires – To be blanched or gay-painted by fumes – to be cindered by fires – To be senselessly tossed and retossed in stale mutilation From crater to crater. For this we shall take expiation. But who shall return us our children? [The Winter of the World] ***** This post is already too long, but I cannot leave without this poem from December: The Oxen by Thomas Hardy Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock. “Now they are all on their knees,” An elder said as we sat in a flock By the embers in hearthside ease. We pictured the meek mild creatures where They dwelt in their strawy pen, Nor did it occur to one of us there To doubt they were kneeling then. So fair a fancy few would weave In these years! Yet, I feel, If someone said on Christmas Eve, “Come; see the oxen kneel, “In the lonely barton by yonder comb Our childhood used to know,” I should go with him in the gloom, Hoping it might be so. Edited 11 November 2023

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed