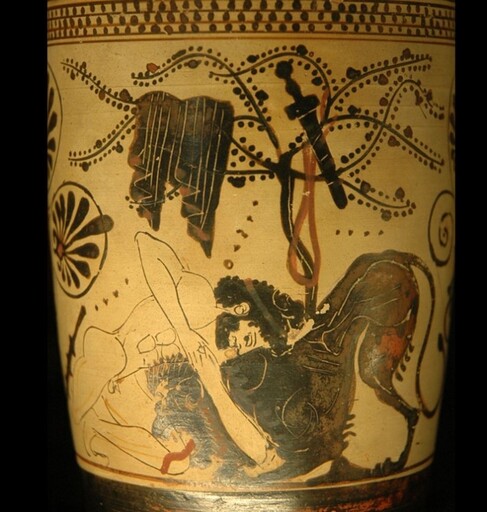

White-ground lekythos, ca. 500-475 BC. Attributed to the Diaphos Painter. Public domain (Wikipedia). José de la Heredia (1842 – 1905) was a French poet who was born in Cuba of a Cuban father and French mother. He was educated in France and settled there with his widowed mother. He is best known for the 118 sonnets in Les Trophées, published in 1893. He belonged to the Parnassian group of poets.

I probably came across Heredia when I was using English prose versions to “translate” poems in the Greek Anthology. I often found his sonnets difficult to follow, but beautiful and intriguing. I also liked the scope of Les Trophées--world history (though from a Western perspective; he wrote in the classic age of western imperialism), and nature poems. There are poems on Greek and Latin antiquity and the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and a short section on the Middle East, the Far East, and the tropics. My attention then as now was devoted to the treatments of Greek and Latin myth and history. The second poem in the collection is “Némée,” referring to a location (Nemea) and the Nemean lion, a beast whose golden hide was impervious to weapons and whose claws could penetrate human armor. Némée Depuis que le Dompteur entra dans la forêt En suivant sur le sol la formidable empreinte, Seul, un rugissement a trahi leur étreinte. Tout s'est tu. Le soleil s'abîme et disparaît. À travers le hallier, la ronce et le guéret, Le pâtre épouvanté qui s'enfuit vers Tirynthe Se tourne, et voit d'un œil élargi par la crainte Surgir au bord des bois le grand fauve en arrêt. Il s'écrie. Il a vu la terreur de Némée Qui sur le ciel sanglant ouvre sa gueule armée, Et la crinière éparse et les sinistres crocs ; Car l'ombre grandissante avec le crépuscule Fait, sous l'horrible peau qui flotte autour d'Hercule, Mêlant l'homme à la bête, un monstrueux héros. Hercules and the Nemean Lion (1st draft) Since the Breaker of Beasts entered the forest tracking the frightening pugmarks in the clay, only a roar has betrayed their fierce embrace. Everything is quiet. The sun dips and sets. Through thicket and bramble, across a clearing, the frightened herdsman, fleeing towards the city, turns. Eyes widened by fear, he sees the beast, stopped beside the woods, rising. He cries out; he sees the terror of the lion whose jaw is gaping open to the sky, with his maw of fearsome teeth, his straggly mane. For shadows that creep from the twilit trees are making, under the hide draping Hercules, a monstrous hero, blending beast with man. Understanding the poem may be difficult for modern readers, because Heredia assumes intimate familiarity with the story. In the third line of the first stanza, for example, he refers to “their embrace” (“leur étreinte”) without providing an antecedent for their—an “oversight” that would probably evoke comments in a contemporary poetry critique group. My title, “Hercules and the Nemean Lion,” gives the modern reader a starting place and an explanation for their. Heredia also feels no need to explain étreinte/embrace, a rather understated way to describe the action to come—the hand-to-paw death battle described in the myth and further discussed below. The beginning of this line had another puzzle for me: “Seul, un rugissement a trahi…. Only a roar [or, one roar] has betrayed….” Some background reading clarified: since Hercules’ weapons were powerless, he used his hands to kill the beast by strangulation. Heredia’s version implies that the lion can manage only a single roar before his breath is cut off. I was also puzzled, briefly, by the switch in tense from past to present perfect (from “entered the forest” to “has betrayed”). I wondered about the point of view implied by the change in tense. The next line is in present tense, as is the following stanza (see the third line), but in the second line of that stanzas we find at last the point of view—“le pâtre/the herdsman.” What the herdsman sees, and what we see, is from a distance—the lion stopped at the age of the woods, mysteriously rising, presumably on his hind legs to grapple with Hercules; the lion’s fear; his fanged jaw opening on the bloody sky; and then the hide draped around Hercules (“floating around” him, in the original), for in the myth Hercules removes the pelt and head with the lion’s claws to use as his armor and helmet. The reader must bring these details to the poem. In the gathering darkness, the herdsman sees a monstrous mingling of man and beast. Heredia’s use of monstreux/monstrous introduces another difference from today’s poetic practice. Monstrous meant, originally, a malformed animal or human, often a creature afflicted with a birth defect. Older museum exhibits used to display canisters filled with alcohol and deformed births labeled “monsters.” Later, the term meant an enormous or prodigious animal portending doom. These meanings are greatly attenuated now, and the attitude towards the abnormal has also changed, so it would be harder to use the term in a poem. The same is true for other terms used by Heredia--formidable, sinistre, and horrible. In general, we would likely use fewer adjectives of any kind. These exhausted terms, as well as Heredia’s assumptions about his readers’ background knowledge of classical myth, are barriers to a contemporary appreciation of his artistry and subtlety. Final notes: (1) I wish my rhymes were fuller and richer (especially mane/man) and followed more closely Heredia’s Petrarchan scheme. (2) I recently learned the term pugmark and used it here, where pawprint would probably be more suitable. (3) The final tercet departs furthest from the original. Speculation: Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde appeared a few years before Les Trophées, making me wonder if the devolution of the doctor into the animal-like Hyde influenced Heredia’s understanding of the monstrous man-beast. Since Heredia’s poems were apparently written long before publication, it may be unlikely on chronological grounds, if no other. Please direct any comments to [email protected].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed